Blue Guitar

Twilight on the eve of the winter solstice: the sky filled with death, blood seeping west, heartbreaker blues deepening above into purple. It will be terribly cold tonight. Winds race down from the father’s north like fierce angels. The mountains to the east of town look like tomb guardians as they catch the last splashes of sun, granite bathed red, mute under their vast snow crowns.

In the valley, it’s already dark. The city’s lights glitter in the hard cold air, a lower sea of stars. The moon rises over a river that cuts through a black canyon of stone. The river is only a trickle, since except for the mountains no snow has fallen all winter. Everything’s bone-dry in the subfreezing maul of the wind. Pines bend and whisper: long night, long night.

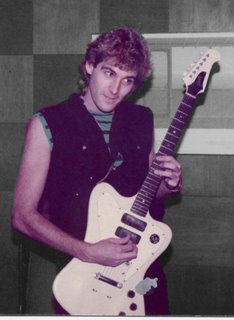

Duke sits by the heating grate in the house he sleeps in and his band practices at. A quart of beer nestles between his legs. He riffs stiff arpeggios on his Strat, trying to work some life into his cold fingers. The guitar is midnight blue and in mint condition. When Duke holds his guitar he feels somehow safe from the cold that invades every precinct of his heart.

A pickup truck pulls up outside, followed the screech of a ‘52 Chevy skidding to a stop. Duke’s door flies open, blasting away the room’s warmth. Paco and Vincent stomp in carrying guitar cases, followed by drum devil Meatball, two sticks poking out the rear pocket of his jeans.

“Fucking cold,” says Paco, stashing beer in the fridge. A transplant from California, Paco like Duke will never acclime to the winter.

“Fucking bitch,” Vincent adds. His girlfriend took off with his car last night with two guys who came over to look at one of Vincent’s guitars and hasn’t called. He stoically pulls out pipe and dope.

“Fucking JOB!” Meatball bellows, kicking over a chair. Paco and Vincent roar back their agreement and give other furniture equally vitriolic kicks. It’s a miracle they ever have anything to sit on.

Duke remains next to the heat vent, nestling closer, trying to believe there will ever be enough heat to warm him. “Fucking fuckoids,” he mutters.

But everyone’s in a good mood, as good as ever: pissed, and hungry for pillage. Tonight they’ll run through the second set, drinkabuncha beers, check out a party way out in the valley.

It’s cold in the basement as they set up. Worse, they haven’t practiced for three days. They launch into the set sounding like an epileptic ‘Vette, sputtering, coughing then dying in a cacophonous saw into silence.

“Motherfuck.” Meatball glares axe death at Paco, who’s flubbed the middle eight of “Murder in Disguise” on bass.

They go on. Vincent forgets the lyrics to “Sin City” and Duke breaks a string during his solo on “The Thrill of it All”. “Shit!” Meatball fumes. “Why did I ever exchange the New Barbarians for this toilet of garageholes?” No matter that little incident of arson that immolated the Barbarians’ tour van. Meatball may be a felon, but what a drummer. He warms up this way, limbering up along a rising gradient of fury.

They crack open beers, pass a joint, curse the winter’s grip on everything. For Duke, moments like these are like when a woman holds him too long. The bare ceiling light gives everyone massive brows and dark eye sockets.

Volume in check, they start again. They go slow and measured. Duke fidgets endlessly with controls on his amp and guitar. Meatball inches a highhat closer, hawks spit into a corner. Vincent’s mouth sets, coolly cruel. They’re all getting set, closing their eyes. Aiming.

Two songs, three, then they find it, the whitewaters of the Conduit. Meatball smiles, ferally, and nods to the band. Time to hit it, boys, pedal to the metal and balls to the walls: and Paco sings,

God and Devil dancing

loving the spoor of our eyes

Day and night romancing

beneath the roof of the sky

We love a deadly wonder

and hide beneath love’s cover

With a dagger on our lips

Living in the rip

And the room isn’t cold anymore and they aren’t a bunch of dickheads working shit jobs who can barely afford payments on all this fucking equipment;

Tearin it up

Living in the rip

Duke swings his guitar like a scythe, cutting in broad angelic sweeps everything that doesn’t count or is too hard to work for or can’t be easily found, oh terrible blue bladed wind, and suddenly the band is home now, plugged in, spring’s river pounding blood in their hearts, everyone struggling to stay loose and cool in a typhoon:

The hourglass is empty

The shutters have all blown away

The moon has filled our eyes

It’s time we made our way

We love a deadly wonder

And howl beneath its thunder

With a dagger between our hips

Livin in the rip

Last song of the set, anthem time, Meatball thrashing his kit, Paco staying with him on bass, Vincent and Duke trading solos,

Livin in the rip

Tearin it up

Livin in the rip

Livin it up

and Duke finds it in those final bars of that last song, while they hold the last chord and choke the sweet motherfucking jesus out of it, while plaster dust falls from of the ceiling and beer bottles dance like crazed elves on their amps,

Tearin it up

Beggars at the cup

he finds it in the floodwaters drowning his desert heart with a pure fury, finds a homecoming for the lost child, roaring into the blue robes of the Madonna, Queen of Heavenly Night,

Livin in the rip.

. . .

It’s around ten-thirty when they leave for the party. Duke rides out with Paco. They pass a joint, take some speed known as Blue Fire, pick up a sixpack to hold them over.

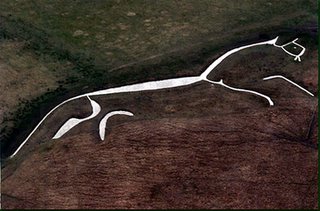

Duke watches black fields of wheat and remembers a dream: he’s walking on the moon, a far isolated zone with a terrible cold he can’t feel. He’s naked and painted blue like a Pict. Dark black birds circle above. It seems they’re bizarre entropies of human beings, vulturous, envious of Duke’s tender flesh. At the end of the dream, Duke recognizes on the birds the faces of Meatball, Vincent and Paco.

Paco speedbabbles as he drives: “So it’s just another night with the squeezaroo, the Prima Donna, but tonight see she’s got on these red lace garters, something I have the fondest affection for you know, ever since high school when I played in the church band and Elaine Quiggen’s blouse snapped open during her sax solo and I got a tour of black lace Tetons...” Paco’s feasting at this verbal smorgasbord, gobbling any thought that rises. “Anyway how’dya like them new bass strings they’re called Ground Rounds, real fat and meaty sound huh...Did I tell ya the union organizers were by the plant again today? Said we were being strapped over a barrel and raped! Like to try that with Prima Donna sometime...Hey, check out these sneakers, black with red laces, whadda cool stage look...Oh yeah, Prima Donna’s got a new roommate, this darkhaired bitch named Lilith, sez she’s a witch, she’s got chicken blood in the fridge and a goddam bullwhip, no shit.”

Duke watches his breath steam. “This is the death of the year,” he says, almost too softly. His hands are jammed in his leather jacket but he feels no cold. “If only I could always be here, forever Heading Out on the final night of the year, numb except for this red blade of hunger to razor the blue.”

Paco looks over, pained. “Get a grip, willya. Pass me a beer.” Duke’s always pulling this wierdo shit.

Paco’s off again as Duke rummages in a bag, pulls out two cans. They crack open in wet spouts. Duke pulls hard on his. “Here’s blood in your eyes,” he says to the moon.

. . .

The house is a ways out from town, alone at the end of several miles of dirt road and scrubrush. Cars jam everywhere, Godzilla teeth. Paco and Duke hear the band playing a quarter of a mile away. The house wobbles with inner frenzy. It’s door is a dark mouth that sucks them into mayhem. Inside, all the furniture is jammed against a wall and a vicious mess writhes, jerks, downs, catcalls, drags, hollers in murky, almost viscous light. Duke is terrified: proximities kill. He recognizes the band, friends of his, jamming to a bunch of old Stones tunes. A conga line of revenants have just paraded onto the stage wearing multicolored panties on their heads.

“Have you seen Meatball and Vincent yet?” Paco screams at the host, some guy in flight jacket, aviator’s glasses and black silk scarf, clutching a quarter-full bottle of Jack Daniels.

He hands Duke the bottle. “They’re out in the kitchen, I think.” Duke takes a slug of whiskey, sighs. When Meatball and Vincent head for the kitchen that means chicken with switchblades and lupine assaults on everything and everybody edible. Duke knows already they won’t be invited back.

“Beer!” Paco screams.

“Out in back,” the host hollers, turning away to follow three very drunk, giggling women, triplets, all in blue silk dresses and red stiletto heels.

A wall of party hyena flesh separates Paco and Duke from beer. Paco charges, cutting through the crowd like the prow of a ship. Duke follows, head down, trying not to be seen, trying not to notice.

But Duke’s eye strays, and he sees her close to the kegs: leaning towards another woman, trying to listen, smoking a cigarette. He knows he’s never seen her before, but some recognition shouts within. Blonde hair in curls, pale freckled skin, blue eyes, tall and wearing a denim jacket and miniskirt. Her eyes are half-closed, winnowing through the crowd like channels on cable tv. She looks by him, then returns in lazy focus. She smiles faintly. At that moment Duke wants to die more than he wants her.

The harder he presses toward her, the more tightly bodies knot the distance. She remains still, in freezeframe, looking at him with that slightest smile. He tries to get past the last person separating them, some asshole who’s recognized him and wants the girl he’s trying to pick up know that he’s a friend of the band, when Duke hears his name shouted over the p.a. where are ya Duke, c’mon give us a song. He turns to figure out what the fuck, and when he turns back, desperation hammering in him amid the harsh cacophony of cheers, he sees the woman walk away into blue veils of smoke.

. . .

They launch into their set, a bit sloppy from their collective buzz and unfamiliar instruments. But the crowd is a mean surf: their dark hunger pumps into the band like shotgun kisses.

Soon all is abandoned to the sheer violence of the song. The animals Vincent, Meatball and Paco find their anger’s zenith onstage: they erupt, go mad, flail, wail, rage, horsecock the crowd. And oh how the crowd widens to it, leads with the chin, begging for the pure parabola of the knockout punch.

But Duke’s heart pelts in its cage, trapped by the attention of the crowd, a pretty puer with long blonde curls, puppeting their desire with a cherry-red Flying V guitar. He feels terribly exposed up here, yet he too delights, if in the absolute terror of it. The front row jailbait scream for him - they’d probably tear him apart if they could get their maenad’s fingernails into him - for the pretty poppy of hair, the blonde hovel of Eros. Duke smiles sweetly. He knows the stage is both his only defense and personal guillotine. He shakes serenely to the violent grinding that towers around him.

. . .

The last chord crashes down, and with it tumbles a stack of Marshall amps; then the drum kit splinters in every direction. Duke’s outraged ex-friends storm onstage to humbug with Vincent and Meatball. Paco dives, swan-style, into the audience, mike still in hand, his cup of beer splashing a glittering amber trail into twenty gape-mouthed faces of crowd. Soon fights break out everywhere.

Duke crouches behind the stage with a beer, ducking a cymbal whistling overhead. Oddjob’s high-hat. The room is a frenzy of howls, shattering glass, breaking furniture, girlish shrieks. Beer and blood pools into glistening eddies on the floor. Duke watches it all quietly, fascinated with the savage ballet of things falling apart.

. . .

It’s 3 a.m. and Duke smokes a cigarette in a bed not his own. Blankets heap everywhere. Sweat dries on his chest, horizontal passions of bed layered on vertical paroxysms of stage. Candlelight flickers on the far wall. A radio on a nearby bedstand plays stuff you never hear during the day, songs for the far at sea. Flotsam of passage litter the room: cocaine dust in a hand mirror, beer cans jumbled like failed depth charges on the floor. Duke’s been up since six in the morning, beyond weary yet further from sleep.

“It isn’t like I meant to run away,” Duke whispers, blowing blue smoke rings into the gloom, “it just happened, I woke up three thousand miles away with an empty suitcase and blue guitar. The summer had passed and autumn meant too much alcohol at night and colder mornings, the rot and rout of the year, wind in the pines sounding like a oboes or a woman moaning alone in a room.” Turning on his side, Duke stares out a window where moonlight bathes the pines in cyanotic, arch sadness. “I looked for the river but it had dried up, the spring runoff had long boiled to sea, virgin greens yellowed and cankered, the rock and roll bars were empty, no connection formed a smile, nothing to suffer waste and boredom with but a blue guitar and these harbors...”

A toilet flushes, the bedroom door opens. The woman is lit from behind by the bathroom light. She pauses there, shadow cupping breast and belly, one hand on the door, the other running through a tangle of curls that falls over half her face. Nineteen, twenty? Duke’s getting old for this shit.

He knows it’s just his intoxication and the tricky light, but water seems to be flowing silently over her feet. Crystal heartbreaking blue water. He can hardly see her but she looks so familiar! Maybe a song he wrote once, when he believed. She walks toward him like the river once in him, dangerous, smiling, surging.

Duke can’t think of any real words to say to her. She smiles, nestles into him, his hand works through her curls. Moonlight sings in the window. Soon the bed rocks gently, a boat on deepest night.

. . .

The girl sleeps, unaware Duke walks home. It is nearing dawn and bitterly cold. Close to zero. The moon has set behind a western ridge. Stars burn, preternaturally bright. Duke’s walked a couple miles already and has a ways yet to go. His blue suede boots beat a tattoo on the sidewalk.

These neighborhoods tell him nothing he wants to know: windows black, dead hulks sleeping dutifully, wholly mortgaged to the day. Families live in these split-levels and white clapboards, husbands and wives, parents with children, television-watchers, people who own cars, pay bills and make monthly savings deposits. Duke walks spectrally through these streets, breath-mist tearing from him, disturbing the dreams of dogs.

His steps, lighter than air, carry him the only way he knows how to go: away.

. . .

Duke doesn’t know why, but he finds himself turning down streets not his own. Soon he’s standing at the door of Prima Donna’s apartment. He knows Prima Donna’s not there, since Paco likes to postgig in a huge, heart-shaped bathtub filled with bubble bath in the basement of his house.

It must be 5 a.m. The door opens a crack. Dark eyes peer at Duke. “What the fuck you want.”

“Don’t know. Cold. This winter’s killing me.”

“So why don’t you go play your silly rock and roll songs till you get warm, or fucked, or fucked up.”

“Doesn’t work. Need more.”

“Ha. Who doesn’t.”

“Please.” Duke looks pale and old.

Lilith pauses. “Another fucking mendicant,” she sighs, unhitching the chain.

Duke follows Lilith into her dark apartment. After his walk, it’s warm as a womb. Candles light the hall. She floats ahead of him, wearing a blue robe, not that cheap velour but real velvet, with a dark satin collar. The rich robe slides sinuously over her body, gathering in dark folds. Black hair falls heavily down her back. More candles flicker in the living room, where there’s a couple of chairs, a coffee table on which sits a pentagram of votive candles, and along a wall a fireplace where a log burns deliciously. Duke hurries over to bathe his legs and chest in firelight.

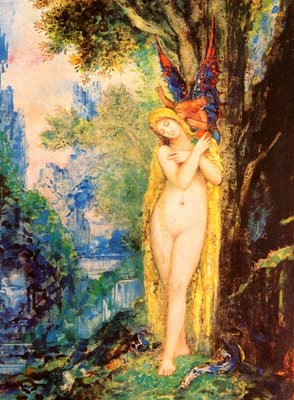

“Tonight is the winter solstice,” she says, rummaging through a wooden box sitting on one of the chairs. “Not one of our High Sabbats, but important for you men. In the old days, the King of the Waning Year finished off his half-year term tethered to an oak altar on the night of the winter solstice. He was hacked to pieces by twelve merry men who drank his blood and scattered the rest to fructify the land. They packed his head and genitals on a boat to float the underworld river. Six months later, at the summer solstice, he was reborn at the ritual murder of the Waxing Year king. The eternal round, two sons warring for the favor of the Goddess.” She says this in a practiced, almost disinterested monotone. “Much harder to find kings in those days.” Wind whistles around eaves of the building.

“I want to be king,” Duke whispers. He’s taken off his jacket and shirt, dropped them in an abandoned heap next to the flames. Waits, shivering.

“Lovely fool,” Lilith smiles, so faintly, holding her bullwhip. “You aren’t alone, really. Others have come tonight. Donna sure gets around.”

Duke places his hands on the mantle. He sees her in a mirror: Lilith’s robe has opened and she’s naked, her flesh a shocking white in the dark blue folds of the robe. The bullwhip coils black and tense in one hand.

A flush rises to Lilith’s face and chest. “You will have your dark mother’s kisses. I will paint pretty flowers on your perfect flesh. Here is your Grail at last.” Lilith’s eyes are huge, like an owl’s, and gleam firelight. She smiles, so full of lust, her teeth dazzling.

Duke sobs quietly, his gratitude leaping into the mothernight with each strike of the snake.

. . .

Duke watches the paling east as he limps final blocks. Can he truly be coming home? He winces in his shirt of flame, beyond exhaustion, beyond drunkenness. Beyond. Is dawn truly a door? His breath is jagged. Blood has frozen on curls of his hair.

A bare light bulb burns in the window of his house. Duke walks in his door to find a catastrophe: those intrepid partiers Paco, Vincent and Meatball have trashed the place. Fridge on its side, spaghetti leftovers spattered on the wall, beer cans thrown everywhere. A record plays the same three words over and over and over and over and. Chairs legs splay helplessly, like toppled cockroaches. And on the floor is an amazing loam of stuff, broken potato chips, ebony shards of jazz records, shattered pint-bottles of vodka and bourbon, a deck of pornographic playing cards scattered in fifty-two positions, baggies with only seeds and stems left, a torn Polaroid of those two Idaho cowgirls the band rode herd on last summer, a mutilated sneaker (Paco’s, stuffed with what Duke hopes is bean dip), guitar picks, crusts of pizza, a flat tire (off Meatball’s Chevy) and the entire contents of Duke’s underwear drawer laid over the mess to spell “S.O.S.” In the bathroom someone has written “Dukie till ya Pukie” in lipstick on the mirror. There’s vomit all over the toilet.

Amazingly, Duke finds a beer in the toppled fridge. It’s covered with a red Day-Glo condom. Duke grabs it by the condom. His guitar is tied by a brassiere to the ceiling lamp. Duke turns off the light, frees his guitar, carries beer and guitar over to the heat grate.

Duke sits slowly, heavily. He kicks the clutter away to form a rough semicircle around him. He feels nothing rising through the heat grate. Duke holds his guitar, runs his fingers over the worn frets. Sweat has dried on the dark blue finish. His fingers are blue, too, frostbitten maybe.

But it doesn’t matter. He watches the room fill with pale blue light, like water, washing away the night’s putrefaction. How beautiful, he wonders, how noble. The sun will soon arrive to shatter the dream, but no matter: only now counts, that final beer, holding his blue guitar so lightly and playing so soulfully with fingers no longer capable of error, his heart purged of the longing at last, a dying ember in the rigor of blue.

(1993)