The Masculine Birth (on Creativity)

Myth’s road plunges ever deeper into a half-lit and semi-aqueous veld beneath the undersides of the known: digging into roots, dowsing for mysteries in personal and collective histories. The further I go, the more I recede; old and older figures appear on the misty road, speaking in older, sea-sounding, tongues, deepened with the resonance of great stone cathedrals at the bottoms of sense. Such daily dark perambles -- call it mediation, call it study, call it nonsensical passions on paper -- harrow the insides of great fires. What is it to stand inside passion so fully as to soak one’s soles on the lost godhead still resonant there? And how can that so paradoxically seem fated, charged a candescence that is not behind but ahead, lamping a way forward?

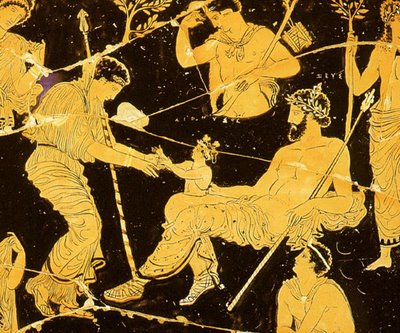

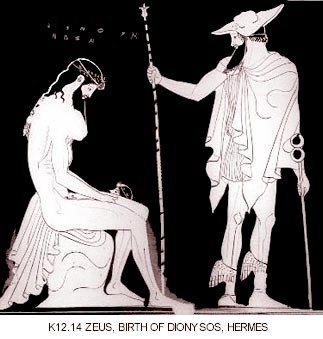

To wit, I’ve been reading Carl Kerenyi’s “Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life” (again, I read it a bit then set back on a bookshelf in my study where it ferments a blacker wilder juice--a charnel Pinot Noir--), and engage the stories of Dionsysos’ second birth from the thigh of Zeus. Zeus emasculates himself to bear this fruit, sacrificing his godlike zeal for rampant and indiscriminate couplings to become a woman, give birth to this son. And the son who emerges from his thigh, looking very much like an emboldened stout penis, is somehow seen as essentially non-sexual: perhaps preter-sexual, the sex inside the sex which from that perspective is not sex but its divine agency.

To quote here from Kerenyi:

”Two characteristic Dionysian idols, both easily fashioned, were in use in the Archaic period. They complemented one another and bore witness to a myth of Dionysos that never became as public as that of the thigh birth. One of these idols was unphallic. The paradoxical term is unavoidable: the unphallic character is stressed. Not only in comparison with the pronouncedly phallic beings who appear as the god’s companions and worshipers, but also taken in itself, this idol lacks all phallic suggestion. Over a column in the sanctuary a mask was hung and below the mask a long undergarment -- which also embraced the column. A column with a capital is a recurrent component of this rigid composition, which can also include plant life; branches can grow from it. The column can also be without a capital, that is, it can be a post, but -- and again this is stressed -- the post does not resemble an authentic herm. Sometimes, even when the idol is standing out of doors, it bears a capital, which seems to have been added for the sole purpose of avoiding all resemblance to a herm and stressing the column character. ...

***

”... This type of idol also occurs in the cult of Osiris and a myth recorded by Plutarch relates it closely to the dead god. Osiris’ coffin, according to this myth, was borne by the sea to Byblos where it washed ashore at the foot of a heath tree. The tree grew around it, so that it became part of the tree. From the tree a pillar of the royal palace was made. There Isis, searching for her husband, found him in the pillar. She took the dead Osiris with her, but she wrapped the heath column in a garment, anointed it with oil, and left it with the kings of Byblos to be worshiped in her own temple. ...

”... this type of cult statue in a renovated form. The mask, which was originally carved from wood -- probably fig-wood -- was copied in marble about 530 B.C. and retained its character as a mask except for the highly impressive eyes given it by the sculptor. They gaze at us like the eyes of a bull. This may or may not have been the artist’s intention, but it fits in with the god’s re-emergence from the underworld in the form of a bull.”

***

What are we staring at here, and why is such care taken to desexualize an image that is bordered with such ithyphallic itchiness? Seems to me the Greeks of the classical period -- where much of the stories of Dionysos were written down -- were digging forward into an old myth, harrowing a truth within the safer margins of art: making semi-conscious what before had been pure annihilating thrall, and, by so doing, giving us a ledge upon which to stand and observe sacred mysteries, a column upon which the mystery still vaults, even today...

HYMN TO DIONYSOS

You were twice-born when

we at last could see a far

older god. You stood there

bloody on your father’s torn lap,

rigid, serene, columnar

as no herm before could

stand, as if the desire

which once so bound and

thralled us now vaulted

a sublimer roof. You, fire

inside sweet wine, berserker

of the mind’s self-wreathing,

emboldened father’s scepter

into a leaf-tipped spear.

Then supplanted all he built

just by opening your eyes.