A Skull Miscellany (2)

Happy St. Oran’s Eve, patron saint of Halloween! Time here to celebrate his bones which relic in our own stone bone, basalt cave of beginings, shore of shattered cliffs, dragon back of wild Upffington, henge of every stiffie shaken at the sky, Eros and Thanatos coiled round his head stone, floor and door, dark fire haloing every harvest moon.

Yes, celebrate ... go trickertreating, exhume Yorkick monstrous jest, shoe the dragon and saddle Leviathan, roger and romp and jolly rumpus this pale imitative world: A bit of banshee shriek and trooping Sidhe, singing Oran’s birthday song!

***

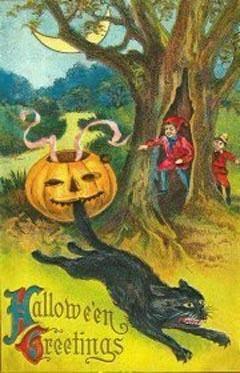

HALLOWEEN

1996

The jack-o-lanterns glow on porches down the street

with flickering grins of flame: burning on this night

the ancient ruse of fancied horror. On TV the rictus

legion of slashers and vampires sleuth their victims

smooth and caressingly as the blood silk lining

of a cape. It's for the kids, we say, stocking

our plastic pumpkin with candy to the brim:

but we'll eat all the kids don't, and scare ourselves most: It's our treat.

Such pleasures still haunt this creaky boneyard night.

Alas for those poor Christians, who sulk the sidelines

decrying all this as Satan's dance, or stage their own

haunted houses as a bit of real hell. Tape recorded moans

of the unconfessed dead crowd the dark front room, where

a carpet salesman cloaked as a demon tries to scare

pimply pubescents into the folds of the Everlasting Hope Church.

The kids are willing victims, the easiest marks for a lurch.

He leads them through ever darker chambers of sin:

he sighs for the blackened soul of an AIDS victim

dying of alternative lifestyle; gloats over the wet plop

of an aborted fetus in a butcher's room (would have grown up

to be a preacher, he jeers); applauds the twisted carnage

of a drunk driver's dance with a wall. Finally, in the darkest

deepest reddest room that reeks of smoking limburger, mark

how all seems lost -- but then the lights come up

and a janitor dressed as sweet Jesus appears to all, to cup

salvation over all who kneel. Salvation from what, I wonder,

as I look out this window at some kids racing in sugar thunder

up to our house, and pray that the mute misery of our jack

-o-lantern spread crooked and lavish its flaming rack

of teeth: trick us or treat us, but let the night squeal,

and good heavens please spare us from the jaws of the real.

THE UFFINGTON HORSE

2003

The locals say I am the beast

St. George slew, his white sword nailing

The heart of this hill. Well, time weaves

Tales around the hearts of men, but

I am no altar to the need

To kill the winged insides of

Every kiss. Recall how kings of

Old were taken up the hill to

Mount a pure white mare, his flesh in

Hers turned sceptre beneath the white

Applause of stars. I Rhiannon

Ride this high ground like the crest of

The ninth wave. My saddle is a

High hard throne -- mount me, if you dare.

Plunge your song in salt everywhere.

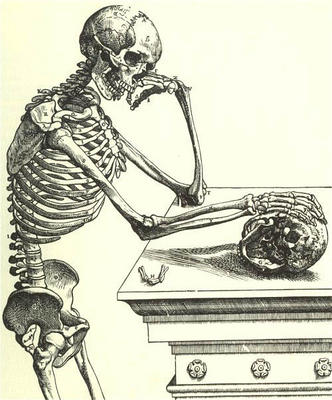

BONING THE GHOUL

2002

An appalling sweetness

slipped into view

when I lost the last

wet curvature of you:

Well, “lost” is landfill

for all tossed verbs,

numens of that last kiss

trucked from dead suburbs.

Atop that dread mound

an eerie twattage glows

as ghoul cockage choirs

in solemn, bony rows.

That chorus sings to me

the beat-to-hell old news

that I’ll not find her again

not even in rear views.

Who knows why forsaking

me was for her so easy,

why she drained the glass;

Or why her sleazy

voidings like a vacuum

in me yet clench,

a vertigo in all makings

with a familiar stench,

deigned to rule a wold

of cold and moony nights

with thorn plecturings of

strings no longer white,

their amperage sucked dry.

What’s horniness if it

douses not in fire

but bone-dry recit,

unbuttoning not blouses

but stone lips of banshee

rue—burning wicker men

because some dame decreed

my hands anon away?

Who wants to fornicate

unnippled sprites of ire?

Let’s banish hope, excoriate

the lust: debone the ghoul

who haunts the ossuary

of every stiffie lost:

let’s remit the actuary

before tits up it tanks.

She rose up from a wave

of breaking blue joy;

and then without a wave

she disappeared, willing me

this stale and sour undertow.

I’ll not find her on this

beach again: It’s time go:

Time to rearrange

into less salty, surer show:

time for bright diurnals

where fresher boners grow

beneath the fertile loam

of an untroubled sleep.

I’ll plunge on alone now

on waters twice as deep,

ghost-captain of a boat

destined for dryer shores,

calmer nights, no matter

how she always gores.

My recent reading of Erich Neumann’s The Origins and History of Consciousnes found a booming welcome to something that was slowly coming to my awareness. Makes sense than when humans were less conscious, the dark was a much greater feared presence. All that old moon magick and superstition and rituals of exorcism: the conscious flame was a flickering one indeed. But now, seems like we can’t shut the big light off, it just whirls around and around and around, like a lighthouse beacon, nailing everything in its gaze. We are conscious to a fault, light is the new abyss, our synapses jammed in the “on” position.

So when I try to get at the dark sides of things, I don’t mean I’m playing with evil or invoking dread states, but rather that the compensation of this day has to work the other way, flow back towards the heart (as you suggested early on). A conscious dimming, perhaps. With such heightened abilities of the conscious mind (I may be massively fooling myself here), we should be able to return to those dark origins not out of fear but with a sense of trying to partner with the preconscious and preterconscious mind, the instinctual animal who is also our greater angel. (Remember Merlin was the child of the union of a hairy imp and wondrous maid).

Is there a way to ride the sexual as a sort of sea-horse or dragon of great power, turning its infernal procreative appetite toward creative production? Are we growed up enough to risk stepping on for such a ride? I suspect that energy runs like a ley-line back to the Fisher King’s castle, runs right under him, back to the room in which the Grail is keptl, under the terribly old figure who sleeps there — all retired gods, perhaps — back through the other rooms, neolithic and paleolithic, Neanderthal, all of the simian figures, all of the warm-blooded familiars, thence back to the cold-blooded ones, vertebrates, invertebrates, hundreds of millions of years, back through organic to the inorganic, the dominion of stone, of star. What a wild ride that dark energy provides, as long as we understand that we can never master it, never own it, never put it to selfish uses — all of those foibles of the Errant Knight who forgets the difference between Noble and Gluttonous Heart.

Thanatos, perhaps teaches Eros that difference ...

THE DEAD

Eugenio Montale

transl. Jonathan Galassi

The sea that founders on the other shore

sends up a cloud that foams until

the flats reabsorb it. There one day

onto the iron coast we heaved

our hope, more frantic than the ocean

-- and the barren abyss turns green as in the days

that saw us aong the living.

Now the north wind has calmed the muddied knot

of brackish currents and rerouted them

to where they started, someone hangs out nets

on the pruned branches --

faded nets that trail

onto the path that sinks from sight

and dry in the late, cold

torch of the light; and over them

the dense blue crystal blinks

and plunges to a curve of flayed

horizon.

More than seaweed sucked

into the seething being revealed to us, our life

is rousing from such torpor;

the part of us that stalled one day

resigned to limits, rages; the heart flails

in the lines binding one branch

to another, like the water hen

bagged in the meshes;

and a cold deadlock holds us

static and drifting .

So too, perhaps

the dead are denied all rest in the soil:

a power more ruthless than life itself

pulls them away and, all around,

drives them to these beaches,

shades gnawed by human memory,

breaths without body or voice

expelled from the dark;

and their broken flights,

still barely shorn from us, gaze up

and in the sieve of the sea they drown ...

There is, one knows not what sweet mystery about this sea, whose gently awful stirrings seem to speak of some hidden soul beneath; like those fabled undulations of the Ephesian sod over the buried Evangelist St. John. And meet it is, that over these sea-pastures, wide-rolling watery prairies and potters’ fields of all four continents, the waves should rise and fall, and ebb and flow unceasingly; for here, millions of mixed shades and shadows, drowned dreams, somnamulisms, reveries; all that we call lives and souls, lie dreaming, dreaming, still; tossing like slumberers in their beds; the ever-rolling waves but made so by their restlessness.

-- Melville, Moby Dick

***

Very early in Irish tradition a story already existed about the resuscitation of a dead giant which contained the following elements:

1. The saints and his companions come across a grave of extraordinary size, or ... the head of a dead person.

2. The saint's companions utter the wish for the buried person to be alive, either because they are eager to meet such a huge person, or because he may be able to tell them about things from times gone by, or about "the invisible things."

3. The saint resuscitates the dead man or head.

4. The resuscitated person proves to be a giant or heathen.

5. He tells them that he suffers in hell, about the torments of hell, or about the place where he lives in hell.

6. He tells the story of his life and ancestry.

7. He is offered baptism, or begs to be baptised, in order not to have to return to hell. He is baptized, dies, and is buried again.

- Clara Strijbosch, "The Heathen Giant in the Voyage of St. Brendan" Celtica 23, 1999, p. 391

GHOULPLAST

March 2004

I found a skull in the

back yard, on the front

seat of a rusted-out

car sitting on blocks.

I once owned it, the

skull I mean, well

the car too, I wore

both out on the merry

marauding road of

guitars and bars

and tits in jars on

too-high shelves. I

found it there, the

skull I mean, while

I was looking for

another poem, rummaging

through fallen oak

leaves for a broken

snake, I mean its

tail cut off, chewed

off probably by one

of the cats. I’d found

it out there Saturday

as I worked in the

yard raking and mowing

on a hosanna of a

spring morning. Poor

snake, it was still

alive, crawling away

from my rake as I

probed the tiny grey

thing that was bigger

than a worm, almost

as round as the

buried cock of this

poem. I let it go

just then, reminding

myself to write a

poem about it when

I settled back here

in the court of

excavations

exhumations

& starry ululation.

So today I went

looking for that snake

in the back yard, on

this page I mean,

uncovering not a

half-chewed still-

plumbing umbilicus

to chthonic hoohah

but woeful relics

of a wild bad time

I though were well

buried, sobered up,

the major archons

of those nocturnal

motions bound at

the wing and tossed

down into this

purgatory of words.

I held my old skull

in my hands like

Hamlet graveside

of Ophelia his old

pal Yorick’s jester skull,

the noggin huge as

a Neanderthal, perhaps

as old too. He I

brooding on old

merriment, old loves,

old thrall. Gone.

I half-expected

that half-snake to

pounce up at me

from a black eyehole,

at least sigh within,

hiss. Nada. Instead

the wind cranked

up from offstage hands

to moan and whistle

through that rusted-

out ‘76 Datsun 710

I pushed to the side

of the road maybe

18 years ago,

giving up that bar-

car filled with

cigarette butts and

blackouts for good.

One night I fucked

a hot rock chick

in that now splayed

and ripped back seat,

my 6 foot 3 frame

somehow compressed

to four as I boiled

sperm in her thrusting

shouting beach-white

loins. Some scent

of her sex coiled

in the orange blossom-

fume sailing on breeze,

corrupt as booze

and twice as fragrant.

Gone, perhaps, or

soured into that

awfuller smell of

the 1000 other nights

I didn’t score the

hot rock chick,

the sweat and the

futile frenzy of

desire’s crucifix with

its immortally

immoral nails oozing

a pustulent nacre,

that awful smell

from when I crapped

my pants in a blackout

one night when some

of the bartenders at

the Station tried to

push my car up out

of the bushes behind

the bar. Soured in

graverot: almost gone.

I asked my hand, just what

do I do now? Preach

my gospel of blue

motions til the brutes

receive communion

and settle on back

down to dark-as-

sweet-oblivion ground?

I wish I could, but

I don't know words

blue enough to bless

the dead. Instead, I

call on Prosper’s shade

from the hour when

his tempest stilled --

fatherly at last of

foul Caliban when he

said, “this thing of darkness

I call my own.” Indeed.

And so I put lips to bone

and battered steel

and call their evening

home. Somewhere in

the leaves beneath the

oak, just beyond the

borders of our yard,

I hear a snaky shake and

coil, reminding me

to write of him another

day, to let my ghoulplast

hold the rake and

do some honest work.

Maybe then you’ll find

proper burial at last,

salt my seas but good

and buouy that dolphin

boy who guides my hand

along every graveside

stone along this Road

of Blue-Boned souls.

The Life of Colum Cille (Columba), written in Irish by Manus O'Donnell and written in 1532, contains the following episode:

"Once when Colum Cille was walking beside the river Boyne a human skull was brought to him. The size of the skull was much bigger than the skulls of the people of that time. Then his followers said to Colum Cille, "It is a pity we don't know whose skull this is, or the whereabouts of the soul that was in the body on which it was." Colum Cille answered, "I'm not leaving this place until I find this out from God for you."

"Then Colum Cille prayed earnestly to God for that to be revealed to him, and God heard that prayer so that the skull itself spoke to him. It said that it was the skull of Cormac mac Airt, son of Conn of the Hundred Battles, king of Ireland, and an ancester to himself, for Colum Cille was tenth generation after Cormac. And the skull said that although his faith wasn't perfect, he had a certain amount of faith and, because of his keeping the truth and that as God knew that from his descendants would come Colum Cille who would pray for his soul, He had not damned him permanently, although it was in severe pain that he awaited these prayers.

"Then Colum Cillle picked up the skull and washed it honorably, and baptized and blessed it; then he buried it. And Colum Cille did not leave that place until he had said 30 masses for the soul of Cormac. And at the last of the masses, the angels of God appeared to Colum Cille, taking Cormac's soul with them to enjoy eternal glory through the prayers of Colum Cille."

- O'Donnell, The Life of Colum Cillle, transl. B. Lacey, Dublin 1998

***

BIG SKULL

2002

There’s a big skull

in our back yard

satirizing the half

we vaunt as day.

I hear it droning

low old chants

& alms, sad &

deep within its

chapel bone, cold

as time and all

that drained away

while we built and

taught and moved

zand won. Our way

is powerful and

ripe, it’s true—a red

engine of high

rhythms, fleet

furious and blind.

It arcs a future

which has no need

of you and me;

it has cured itself

of the ache to love.

La la la, sings the skull

out back, not exactly

mocking, nor ironic,

but deeply disturbing

as all engraved

jesters are. He’s

exactly what we

cannot stand to hear:

correction from

down under,

God’s thunder

bringing up the rear.

From Jung’s Sermons to the Dead, IV:

The dead filled the place murmuring and said;

Tell us of gods and devils, accursed one!

The god-suun is the highest good, the devil its opposite.

Thus have ye two gods. But there are many high and good things

and many great evils. Among these are two god-devils; the one is the

Burning One , the other the Growing One.

The burning one is EROS, who hath the form of flame.

Flame giveth light because it consumeth.

The growing one is the TREE OF LIFE.. It buddeth,

as in growing it heapeth up living stuff.

Eros flameth up and dieth. But the tree of life groweth with slow

and constant increase through unmeasured time.

Good and evil are united in the flame.

Good and evil are united in the increase of the tree. In their divinity

stand life and love opposed.

Innumerable as the host of the stars is the number of gods and devils.

Each star is a god, and each space that a star filleth is a devil.

But the empty-fullness of the whole is the pleroma.

The operation of the whole is Abraxas, to whom only the

ineffective standeth opposed.

Four is the number of the principal gods, as four is the

number of the world`s measurements.

One is the beginning, the god-sun.

Two is Eros; for he bindeth twain together and outspreadeth himself

in brightness.

Three is the Tree of Life, for it filleth space with bodily forms.

Four is the devil, for he openeth all that is closed ...

SKULL O’ BLOOD

2003

O for a well-bucket

of living memory—

a rich, steaming

cup of blood

fresh as the night

I spilled it carousing

my way home

out of the usual

complications of

self and selfish

oblivions—

Blood in the

savagery of raw

nakedness when

my hand reached

clasped her breast

like the harbor

of a lost island—

Blood in cupping

squeezing &

nipple-pinching the

reality confined there,

getting past all

the staves and punji

sticks which provoke

and fend desire

(lonely, drunk,

shy, broke, speechless)—

Blood in breaching

the self’s prison walls

for a night on a

mermaid shore

misted with the

sea’s own noctilucent

billows.

I recall being 14

on a moonlit night

& sitting on a

parked motorbike

behind a neighborhood

girl & touching

a breast for the first time:

The wander up

under her t-shirt

with trembling hands

under bracups and

then boy-manning

that gelid flesh,

meeting no

resistance for a while:

scared shitless with

both hands on

her breasts while

she sat still and

patient for 30

seconds in that

moonlight til’,

deeming me milked,

shifted away off the

bike & leaving me

there trembling

and united with

those darker lower

regions I carried

like a a lake of

eternal joy:

Oooh rich skull

of my own blood,

bubbling for the

first time &

forever ripe

in the undying flavor

of desire and

fear and daring

which I suckled with

greedy teeth. Dip

your pen in that cup

if you dare, if

you still can, if

you can take

me back there

to stain my lips

with that greedy

hot & lost pulp.

DEMON IN THE WALL

2002

Engraved upon a basement

wall is a devil trapped in rope.

That’s how all churches, hooch-

stills, and marriages begin:

A raw, primordial age

when equal forces saw:

the good which would begin,

a dark which backwards falls.

There is a time when

principalities roar, the balance

terrible, a back-and-forth

over sweet prefecture and ruin;

the mouth which chants

the ululant vowel is also

filled with teeth, filed

to a glittering “T.”

There was a time not long ago

when love and its shade were split;

and on that tortured ground

all decency was spilt, sacrificed,

perhaps, so a carnal

knowing could evolve

from rough magic on to rue,

allowing it a dark enough depth

so I could know for sure

what going home meant.

A boy-man’s down there with

a snake gripped in his teeth;

I’m better off engraving him

lest sleep unloose the rope

and black wings again soar.

THE NEXT PASSION

March 2004

Journalists of soul,

please note: This week

“The Living Dead,” a

re-make of George

Romero’s ghoul opera,

has knocked Mel Gibson’s

“The Passion” from

the top of the box

office chart. Apparently

we eat our dead with

steadfast glee, and

don’t require a cross

nailed so to glut on

eviscerations of

the apparitional Sidhe:

Perhaps the thrall

parallels from viewing

chair to chair, the muse

of worst ends endless

in her gory repartee

onscreen or page or

down the stony circles

where our imagination

yet fumes. How ripe

she dances up there

on the screen, peeling

off her fancies behind

the next victim’s throat-

split scream. Something

of that horror is too

revenant to simply

die away: it keeps

on knocking at the

doors and window

of our age, polite for

now but persistent,

as thirsty for our blood

as we are for recalling

theirs. Counter-Janus,

the faces stare each

other down at this

threshold., imploring,

aroused, even greedy,

the appetites of life

and death far more

dangerous than “vital”

or “needy.” Here’s a

table that we keep

returning too until

we’ve “supped full

well with horrors,”

like Shakespeare’s

bloody knight, holding

court onscreen in

a blue-to-black Hell

Castle reflected from

our darker soul’s

incessant gleam,

devouring for two

hours and twenty two

minutes a persistent

love-sick night.

Black hooves indeed

hammer all the nails

securely in. It’s what

that God requests

on His on way back to Eden--

the next passionate

eviscerating sigh.

AZTEC KISS

2004

A relic of the Aztec

empire’s throne of blood

is on display now at

the Guggenheim — a skull

mask: Back half removed,

eyes fashioned from white

disks with huge black

balls for pupils and —

here’s the cruellest

part part — long

flint knives for nose

and tongue: Those

blades reveal that

age’s eyes were

insatiable for that

red syrup of the

heart: Thier great

gods thirsted

for it like drunks

their hooch:

They also spell

the spillage of

that age, for blood

that is priests

and kings in

gold sunlight

slipped and fell

hard on, all the way

down their pyramids

to doom: Ghastly for

sure but the mask

is vivid, wildly florid,

brilliant at the altar

of that devastating

sun: Knives for certain

are for noon, that sharp

stilled hour when lust

and greed shriek like

the sun-horse’s balls

and the distance between

serrated blade and

pulsing terrified heart

is but one tock

of plunge: Far indeed

such vicious tropes

from those we worship

in this age: Thank

God that sharp

relic’s glow is deep

in a museum’s vault:

Yet not so far perhaps

if that image still clicks

like a switchblade into

sudden truth, those

sensory blades leaping off

the page and all the way

to here: That skull mask

is always trooping through

the day with wide dead

eyes alert as Doom for

the next exposed pulse—

openings in traffic,

a sale ripe for the

plundering in a caller’s

wavering voice: Pangs

of hunger lifting in my

mind the top from

a microwaved tub of

Cuban rice and

beans and chunks of

pork awash in tomatoes

and cilantro: The steely

rage I feel when

I hear our reelected

bubbleboy of a President

on the radio when he

says the word mandate:

When movement in

the corner of my eye

sharpens as I look out

my window at work

into a pretty girl jogging

by, sweaty cleavage and

thumping butt is

suddenly speared by

a bolt of lust that

flings tipped with

that blade, pinning

her against a wall

& tearing shorts

& panties down and

thrusting balls to walls

that skull mask’s pierce

of all the world’s fishes

leaping there: Inside this

nice guy who’s near 50

who writes and rides

toward Love there’s

just below a demon rider

with brash obsidian

snout and tongue of

adder’s fire: The cold

front now slicing

down the state belongs

to him: So I suspect

do your eyes, my blue

Fomorian, and all

that ripens in your

bustier of ice: Every

beloved hoods a knife

inside her sighs which

will not settle for

anything less than the

real mortal bloody

beating deal till death’s

black wombage swells

past full: Every poem

has the slosh and pour

and is lyric as the moon

but understand there’s

a darker porpoise snout

below, chipped and

whetted long ago

to kiss every shore

and keep plunging

through, from well-

hung tongue to

hell’s own bung,

nailing and cleaving

the heart of every

next ripe heart of song.

ENTER THE DRAGON

2005

The Dark -- felt beautiful.

-- Emily Dickinson (Fr. 627)

Beware the scented bed of

Love: it rides upon the

dragon’s back who swims

abyssal realms. Drowse

there and you’ll wake

a molted man of fire,

enrapt inside the rupture

of the devil of deep

welcome. Your wings

will lift you into nights

the size of titan ire,

your eyes whet and keen

for any trace of blue

embroilment to fall,

silklike, from yet

knowable breasts

ripe and leaking

dragon’s milk, booze

poured from paps

of doom. Ride such

nights at your peril,

son of ancient smiles:

Do not presume you

have tooth or troth

sufficient for that dark

demanding angel ride

into the chasm which

splits the fundaments.

Just hold on for your

immortal soul

and let heavens collide

and smash down

every shore. Let every

numen reveal the bestial

depths below, like buoys

singing on blackened tides,

rippled by deep waves

fanning deeper lands

than undreamt Love can go.

When Pryderi returned ((to Dyfed)) he and Manawydan feasted and took their ease. They began the feast at Arberth, since that was the chief court where every celebration began, and after the evening’s first sitting, while the servants were eating, the four companions arose and went to Gorsedd Arberth ((a fairy mound)), taking company with them. As they were sitting on the mound they heard thunder, and with the loudness of the thunder a mist fell, so that no one could see his companions. When the mist lifted it was bright everywhere, and when they looked out at where they had once seen their flocks and herds and dwellings they now saw nothing, no animal, no smoke, no fire, no man, no dwelling — only the houses of the court empty, deserted, uninhabited, without man or beast in them; their own company was lost too, and they understood that only the four of them alone remained.

— “Manawydan son of Llyr,” from The Mabinogion, transl. Jeffrey Gantz

TOTAL ECLIPSE OF THE HARVEST MOON

St. Oran’s Day 2004

Last night the harvest moon

burnt full inside a total eclipse,

as if Saint Oran himself

bore on his feast night

the earth’s voyaging shade.

His boat indeed is dark

inside that pure silver,

mined from every

shores he searches within.

When I woke that harrowing

was over & the moon burnt

high above the west,

a white skull turning the

sky into wild milk, so hot

with noctilucence that it

almost hurt to stare.

Reliquary of the sea’s old

song, vox organum belling

high the narhwals’ choir,

crown for us what sails

our deepest soul, isle for isle

through all loves, all lives:

you are the music inside

the tomb, the man who

sings inside each collapsing

wave’s long boom. Moon

which wombs no-time,

toll that sea-torn note which by

rising and falling all tides

and songs and bell towers thrive.