Shall I tell you a story? Do you prefer history, a love story, a good mystery, something deep, something fleet for drowsy afternoons on a summer vacation's beach? Poetry or prose? Essay or something more scholarly? Shall I woo you with metaphors or wow you with muscular sententces? Shall I shine bright or offer cool shade from such heat, a blue dreamy glade of downy billows?

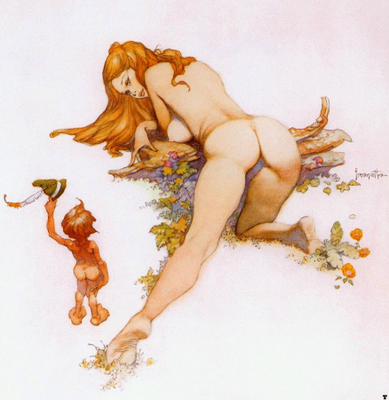

Why bother at all? What drives me to say, to sing? What is it that wants to be told, and am I anything more than its pen, mouth, keyboard? Shall I create a world? Let you feel the curve of my wife's hip as I stroke it at first light, sense its immaculate semblance to the curve of our Siamese sleeping on a nearby chair? Shall I curvelike motion into a deeper, yeastier sea? Do you care to see what lies far down, drowned, animating my anima? Shall I blend it all together into one song, one post? Today, perhaps , but who knows how the skull wil chatter tomorrow ...

***

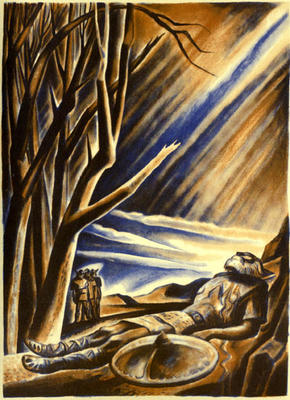

Joseph Campbell was driven to tell a story he was convinced lay at an obscure center of things -- a story which he felt was desperately needed in the off-center, fragmenting culture of the middle twentieth century. "My hope," he wrote in his preface to

The Hero With A Thousand Faces, "is that a comparative elucidation may contribute to the perhaps not-quite-desperate cause of those forces that are working in the present world for unification, not in the name of some ecclesiastical or political empire, but in the name of human mutual understanding."

His heroic monomyth -- tilled from worldwide sources, some as ancient as our dust, others as far-flung as our most mysterious dreams -- is a story familiar to all human cultures, and thus moot for resuscitating our fraying one, like a dead giant or enthralled Merlin or lost Arthur to come to the aid of our contemporary wasting sickness.

21st CENTURYEvery age requires a new confession.- Emerson

Half of me walking

from a dead century.

Launched in '57

with Sputnik on

the crest of the

Baby Boom.

My tit the Sixties,

Watergate my weaning.

I walked off an

ex-Christian geek

who just wanted to

play the solo to

Led Zepplin's "Since

I Been Lovin' You."

Tolkein and Tull

my dormitory spooks

down a far Western night.

Nuclear winter and

Sylvia Plath's gas oven-

Booze, Brian Eno,

Roethke's

Straw for the Firefed to the flames

of one very bad

winter night.

A guitar bridge through

a woman's white thighs

leading to me southern

beaches, the end of

the cold war and

desconstruction. Sex

signifying nothing in

an endless moonwalk

neon-lit by Mikey Jackson's

vanishing nose. Corporate

gigantism in a dinky stockroom

as the last band failed

and I sobered up to

be dad student and

intellectual. Recession

and Iraqi taunts

my distaff, dark mentor,

tormented by a bloodless

air war with its flashy

blade and oh so dark shadow.

I divorced to global

capitalism and the Internet,

a madeira darkening the

sea, harrowing, fattening,

going online and virtual.

Teens take up weapons

and spray illiterate brains.

I remarried inside a secret

bottle and sprayed

the cage with tiger's pheromes.

Didn't work. Terrorist

bombings ashore and abroad

toll the awful clock,

turning one century's wild

page to the next. No

bug worth the millenium's

steel byte. Kept writing

through hell's circles to

plug the jug again and

jog on. What time is there left

to speak of what follows?

A page, maybe two, sending

off as many boats as I can.

I suckled on war and modernity;

the other half of me now

raises sons and daughters

in a wild fosterage,

weedy in its words

and headed deep for the hot heart.

The slaking of our thirst in that story --as evidenced by the popularity of Campbell's writing -- reveals the deep and lasting satisfaction of myth, where so many of its its recent tributaries have gone dry.

Surely the bones of that story -- calcinate reveries of a bliss -- are what Campbell drove him to begin. The ten thousand stories he would later collect from folklore collections, sacred texts, and the walls of dark caves all helped to add muscle and organs to that mythic creature.

What Campbell brought forth out of himself saved him from the shadow of its absence among us. His task was identified with the heroic monomyth (a phrase he lifted from Joyce and glossed from his readings in psychoanalysis): "The full round, the norm of the mon-myth requires that the hero shall nowbegin the labor of bringing the runes of wisdom, the Golden Fleece, or his sleeping princess, back into the kingdom of humanity, where the boon may rebound to the renewing of the community, the nation, the planet, or the ten thousand worlds." (

Hero)

What a strange yet familiar recognition I sure felt reading

Hero and the three-volume

Masks of God! And what an appetite I developed for learning the stories! For five years or so I did nothing but that. Homer, Ovid, Virgil, Beowulf, the Arthurian cycle, the Celtic cauldron of plenty (from Yeats, Graves, Anne Ross & then Fiona MacLeod and Alwyn & Brinsley Rees), American Indian myth, accounts from archeology, anthropology, depth psychology and literary criticism, and then the artists -- Dante, Shakespeare, Melville, Joyce, Rilke. The story drew me into depth and breadth, and I couldn't get enough of it. Robert Bly tells of Campbell, just out of college, going into the woods for five years and reading, reading, reading, "becoming Josesph Campbell;" I read Campbell, and then read outwards from him, becoming a singer of sorts.

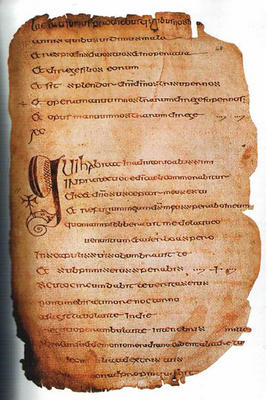

As I've said here before, the old Irish poets were not allowed to write a lick of their own verse until they had learned the entire cultural canon -- the immense corpus of stories, satires, paeans and laments that Irish poets had been passing down, orally, for hundreds of years. You don't tell your story until you know THE stories; there is a correct riff to it, a knowledge which can't be attained except by pouring all of that culture into one's noodle. A good story must have bones; it must be familar and not, and the telling must satisfy a communal need which is familar and not; it resonates with both history and mystery.

Rees and Rees put the storyteller's task this way in

Celtic Heritage:

"In Welsh, the very word for meaning (

ystr) comes from the Latin

historia, which has given the English language both 'story' and 'history.' 'History' has now been emptied of most of the original extra-historical content of

historia, which derives from a root meaning 'knowing,' 'learned,' 'wise man,' judge.' The old Welsh word for 'story,

cyfarwyddyd, means 'guidance,' 'direction,' 'instruction,' 'knowledge,' 'skill,' 'prescription.' Its stem,

arwydd, means 'sign,' 'symbol,' 'manifestation,' 'omen,' 'miracle,' and derives from a root meaning 'to see.' The storyteller (

cyfarwydd) was originally a seer and a teacher who guided the souls of his hearers through the world of 'mystery.'"

THE SINGERSBack in '91 I tried

to form a creative

group of men called

The Singers -- a

marriage of men's

movement drum-

banging to the mythic

background of fireside

tales. It seemed the

right next thing to

do though the result

seemed all wrong.

I culled a few guys

from the Orlando

chapter of men's

groups (on fire back

then, when Bush

Senior was still

whackin' away at

Saddam in Desert

Storm and the economy

was beginning to

rouse toward its roar).

and we met in

the boardroom of

the Orlando Shakespeare

Festival every couple

of Wednesday nights.

Each guy was to

bring to the meeting

a Contribution -- a

story, poem, myth,

song, drawing, something

which voiced a tenor

of our chosen Theme:

Orpheus, Trickster,

Fathers, Mothers,

War Gods, Apollo,

Dionysos, Totems,

Hermes, Inner Guides,

Eros. Fresh-pickled

from three years

of heavy reading

on the borders &

ley lines of those

themes, I dug down

into each with all

the frenzy of a man

with two weeks

to live, penning 30

to 50 pages of notes

on what I found

further down &

shaped it somehow

to take along.

How well I recall

the fraught urgency

of the effort as

I crammed those

studies in long

before first light

there in my dank

study of the Hyer

street house of

my first marriage,

my then wife- and

stepdaughter sleeping

off the previous

night's tangles and

torments, me at that

cramped desk with

a wall of books

to my left and

dark opened windows

to my right, night

buzzing outside

like dim sweet marina,

a small table as an

altar just below one

window, arrayed with

stone votives, a Celtic

cross carved of wood

from Iona (rare, lost when

I took it along to

a company awards

dinner staged at a hotel),

shells, a skull coffee

cup with three I Ching

pennies in the cowl).

Digging furiously

in the dirt between

the lines of Walter

Otto on Dionysos or

Karl Kerenyi on Apollo

or Hillman or Campbell

or Jung or Eliade on

the next god dripping

and gleaming with

the Unknown. -- God

how I filled up those

narrow spiral notebooks

trying to build a

cathedral in two weeks --

And how full, almost

to bursting I was as

I walked downtown

those Wednesday nights,

notebook in hand, with

six poems (three of

my own), two stories

and ten pages of

outline to Sing when

my turn came -- fool.

The gatherings were

always dismal, two

guys not showing up,

a third empty handed

(too busy with work &

wanting instead to

talk about his latest

fall from love); maybe

a fourth and a fifth

would have something,

the start of a poem,

a story somewhat

oblique to the Theme.

For those dozen or

so gatherings -- meant

to be a creative ring

of fire -- I was caught

between a raging fullness

within and a tinderless

green hour without --

no match for the worlds,

certainly few words

for those Singers. After

three or four meetings

the numbers began

to shrink, to five,

then three. The next

time me and the other

guy just talked about

our jobs, since he had

nothing else in hand.

Then one night I

sat in that Bard-decked

room all alone, reading

out loud some riffs on

Hermes that had

kept me almost wild

for two weeks. By then

there wasn't even a

towel to throw in -- no

one else cared even

to fray. Perhaps it

was simply fishing

in the wrong waters --

those men's groups

rode a short wave

then mostly expired --

I might have culled

some scholars from

Rollins College or

UCF with an itch

to dally away from

their riven fields of

-- though today

I think that unlikely

because such studies

are career and die

slowly in that (the

director of the Shakespeare

festival, a prof at UCF,

told me at lunch one

day he hadn't cracked

a book in years). No:

the travail was mostly

mine, or it belonged

to that surgency within

that wanted to see

further in the dark

of time and soul. Singers

just gave me a chance

to go far and deep

and write that passage

legitimately & legibly

down, mortaring the

motions which I still

use today.

In my first of day

routines I read back

over those journals,

culling bits of story

and insight to throw

into my Well, salt those

waters, if you will,

stir the bell to ringing,

get the skull to singing

-- see? A hundred

journals are piled

beneath my tongue,

learnings I will never

quite recall, dissolved

in whale-gut with the

rest of a life (a divorce,

re-marriage, a degree

but no more, five cats,

another job and then

another, a Well, a

poem or two thousand

with three thousand

more in tow), all

those voices stuffed

up the barrel of this

singing pen, a choral

plainsong filling a

paper cathedral which

roots me to a dream.

***

Stories are timeless, but singers evolve. We update tales to fit changing times. As I wrote here last week, Orpheus morphs: from a second-millennium BC shaman whose song carries him to the otherworld and back; to the Orpheus who accompanies Jason in his quest of the Golden Fleece; to Ovid's doomed lover whose song cannot quite return his dead wife to the living; to Orpheo of the Middle Ages whose courtly manners and training as a troubadour allows him to woo his way into the otherworld castle. "Every age requires a new confession," wrote Emerson, and we're constantly retrofitting old tales into new vehicles. Evidence "Star Wars" as George Lucas's attempt at retelling the Hero monomyth. Yet doesn't it seem that revision never quite manages to heft the original? Our worst evidence of this is in the constant Hollywood makeovers of bad television shows which stole their thunder from movies which lifted conceits from novels which stole from local barroom talk and folktales. The further we get from the source, the less potent the draught; that's why Campbell's work as a collector of stories is so important -- so we don't forget that the song of Orpheus really can bridge realms.

We also move on to other stories, genres, rhetorics, poetics. To me the hero monomyth is a good metaphor for the emergence of consciousness and the forwarding of human civilization; yet it is a rather stuck story, unable to change, fierce in its attachment to sticking to the narrative, enacting all of the scenes. It has the riven nature of a masturbation fantasy, the old parade of cheerleaders and floozies endlessly strolled and rolled in the same old hay. To me it's because the hero fights to be free of the mother (unconsciousness, the Great Mother / matriarchal consciousness which held sway over our great middle period, or simply one's personal mother) only to return to the mother, to come back to the welcoming bosom of culture, there to marry, sire the next generation of heroes, and dote in the secure amniotics of home.

SEXUAL HISTORYWe lay in bed all day

fucking and drowsing

and watching movies

on Comedy Central,

the shades drawn tight

against a cloudless hot day

thick with the smoke

of local brushfires.

Telling stories about ourselves

the way new lovers do,

accounting somehow

for the sexual history

that brought us to

this surrender, against

the grain of the

way we thought

we'd go. I stroked

your back and ass softly

as you told me about

the redheaded drop

dead gorgeous girl

who found sex in

a complete clueless

stranger - no one

would tell you about

that meaty thing

that hung from your

father's hips as he

showered with you,

or what it was you

felt riding a horse

at 14. The orgasm

you discovered with

your fingers beneath

the sheets one morning

frightened you terribly.

Your first lover

raped you because

you had no idea what it

was your were asking

for in your scant

bikini working a

surf shop in

Huntington Beach.

Desire was for you

a nameless sum

subtracted by the

world from God, yet

its pure beams always

brought you back

to an eternity.

Then we shifted

and you rested your

head on my chest

idly playing with

my cock while I

told you about my

eternal fascination

with a female's body

and the terrible

overlay of shame which

drove sex into

the vivid shadows.

I recalled the nightmare

I had a six of civil

war at my school,

parental rage embroiled

against my desire.

The kid who told

my teacher of the

games I played with

girls was on fire,

edging round the building

I hugged in terror. I

could not avoid him

and the dream ended

in my smouldering bones.

You laughed when

I told you about

conducting the Dean

girls as they jumped

naked on their beds.

These fires have so

little to do with love

- kindred, ignitory,

initiate liquors for sure,

but even after all that

fucking that afternoon

I grieved my wife

alone in our house

and later sought to

ground myself apart

from you by roaming

downtown bars

drinking Myers and

pineapple and looking

at the faces of women

gathered at the bars.

Sex is most what

it fancies, and love

is greatest when it's lost.

I'm a total fool

adrift outside those

margins, and will forever

hurt those who share

my desire even a little

while. It's a smoky,

drawn-curtains way

I wend through

the current hour.

My truths burn me

from both ends

and what's left

is this charred pile.

HISTORY

HISTORYNo one cares much about history

in the thresh and whirl of this day

which unscrolls through waking's

droll rituals (coffee, poems by

Galway Kinnell, time here)

into the labors of life around love

(a transfusion for the sick cat,

joining a hammer of traffic

aimed at the heart of this city,

hours of making in a corporate trench):

The present is pinched and earnest,

a salty isthmus between desire

and regret: I consume it rapacious

as a wolf in a terrified fold of sheep,

my red canines clamping down on

the next whinnying sweet.

Yet in some hour late in the day

when shadows creep slowly east

she comes to visit me at my desk,

the muse of that backwards glance

which turns a wife into memory

then crumbles that shade into dust.

The muse of history threads beads

on a silver wire, joining them in

the loop of my life. Her news

is always mixed: While every bad

love has me in common, yesterday's

crisis is just a bump I traversed

during happy hour. Sometimes

I wish my tapestry belonged to

somebody's other, more tragic tale,

but that's history.

At some late hour of the day I pull

my history from the shelf and

like a mirror I enquire, shall I go on?

Am I doomed to repeat this tale every day

til there are no more days to lose,

no more loves to foul? But there

is no choice: The fever will return

tomorrow, beyond the next thunderstorm,

and silver swords will beat like wings

of plowshares curving back up

across the fertile sky and

fall toward that sweet bed

just beyond the horizon,

an arc resplendent with every

color inside this heart's dolor,

a rainbow leading to a day

gilded and sweet, the history

I always prayed for, the one

I protect and border and greet

like the woman I'll never

savor or die with or even meet.

There are other stories, IMO, stories which are tandems to a plurality of gods. There are Saturnal depths and Venusian dapplements, sacred islands and itchy-hot bridles: calls to many adventures. For years I clung to a story as my own, growing as I wove the story into my history, writing a case history of boyhood failures and young man's foolery. But then there was a midpoint when things seemed to reverse; I less needed a hero than I needed a more nuanced voice, something more apt for weaving varied realms I was experiencing. Maybe I was moving back toward the older Orpheus, but I became more sympathetic with notions like polyphony, perplex, polysemous, porous, plural. With qualities that were mixed, mercurial, quicksilvered.

SONG CYCLEThere was once

a poetry sustained

between two wills,

the one in love

with the given life,

the other in lust

for another.

A music rose from

those stretching plates,

taut, viral,

pure as all waylaid,

imagined things can be.

But then came

the break with

its grim hooves.

An unharbored music

poured forth

from the wound,

bitter and droll.

A drone.

Next the nocturnes,

a descant metal

falling blue to black,

a drowned woman

bumping against

a reef of pews.

What sings now?

Open the doors and

let it go. Outside the

blossoms are pealing

bells of sweet fire.

The next poetry

is uncertain

of anything else

but plays on,

harping toward

the light of what will be.

***

Maybe that's why I turned to poetry, which is story freed from narrative, the boneless shadow of the giant free to round the vowels. It cuts through the personal and local into the grander epiphanies, where narrative seems to boat on their surface. Why not the depths inferred from surficial glimmers?

But it is most satisfying to practics an even freer artistry, to dance the genres and poetics in the plurality of story. Thus I have a love story and a voyage tale; a case history and a drunkalogue; a bildungsroman, a baedeker, and a triple-decker confessional; a scheherezhade of dreams and a cookbook of daily disasters; a slave narrative and a song-cycle of eternally waylaid beachside consummations; a gospel of tropes and a black psalter of desires; a breviary of guitars and a bestiary of bottoms. There are Penthouse letters and letters to young poets and letters home from camp and the trenches and the workplace and the eternal infernal internal, and all are love letters to the world. Why not adopt the style fit for the tale?

I do believe that the story changes us as we tell it, and each repeating of the story is like a chapter of that education. When I was sobering up I read a story about an Eskimo chieftain who was explaining to an anthropologist about how he brings himself to do good. "You see there are two dogs in me, a good one and a bad one, and they are always fighting, fighting, fighting in me, trying to tell me what to do." "Which dog wins?" the anthropologist asked. The chieftain thought a moment and then answered, "the one I feed the most." The tale I repeat is the one I feed the most, and the satisfaction I take in the tellings is the degree to which the story is feeding me back, nourishing me from its darkest sources.

HISTORY LESSONThe wave which

carried me here

arrived from 15

centuries back

from a shore

which harrowed

a mash of two

faiths. Columba

was the ferryman

of that betweening

age, Oran its dark

and bright page,

each bone a florid

letter, his skull

a door to

the great angels,

whose wings all

ages in their

rhymings rise

and carry one here

to smash on this shore,

this oaken door

opening back or

down or in toward

a time when the

times met in a

clash of bright wings,

when futurity's

soar took wind

on the old roar.

THREE CUPS

THREE CUPSfrom

A Breviary of GuitarsEvery fever of song

was complete in me

at age 14: body

heart and mind

tuned to that

singing saw inside

each wave

of the world

that crashed

over me.

A hi-wattage

channel,

without static,

without peer.

I knew the songs

before I heard them.

Picking up

a guitar,

I returned them

to the world

believing

it would listen.

The story

was complete

by the time

I was 14,

but I had much

farther to go.

Song needs

no story-it's

timeless-but

we do, and

I have much

to say about

how I variously

approached the

music as I

grew into it.

The Irish say

there are but

three songs:

laughter, love

and sleep.

There are three

cups on my

father's bardic

crest, drinking

horns dipped

into those

tuneful vats.

Effervescence,

swoon, and sorrow

have their own pitch

and key, major,

major seventh

and minor modes

of revealing

the world's

polyphonic noise.

At 14 I could

recognize each

of these tunes

as a road

on the fretboard

leading out

to the body

mind and heart

of a woman.

I would learn

they also

wound inwards

to Psyche's

tortured geography,

mapping out

anima and enemy,

muse and mood,

skirt and womb

of all my making.

What I learned of

how song brought

girls and how women

woke my inner ear

is the distance

between hearing

and knowing,

and my life

is that raw

polyphony.

This breviary

of guitars

is about

what I found

in each of those

cups, what I

missed, and

what could not

sate when

I thought

each cup

had run dry.

THE THREE CUPSWhen I read back

through my massed

stone colloquies,

I can see three

motions which

stay pure:

A voyaging mind,

my body's gallop,

this ache for you.

Inexhaustible

those three wells

from which I daily

draw, hungry for

more & aching for

what must rise--

writing the poems

working the bones,

stroking your feet.

What sustains

me in each encounter

I cannot say, but

the bread I find

there is always

enough for today

but never more.

This tells me

that all are of

the same humger

and thus ordained

(or wardened)

by God.

It is also clear

that I always

fail by wanting

more: For grander

fish hauled

from the deep, for

muscles bigger

than my frame,

for right here & now

all day and night.

Blessing and bane,

cool water with

astounding bite,

my altars have

all exceeded

their temples,

grown long

like vines and

red of tooth. How

I've howled in

the old woods

of the vacant word.

Worked this

poor body past stiff

and sore. And

oh my greed for

you, enough said!

God has given me

these preter-thirsts

but its mine to

give them back

to God's world:

No shore final,

this body old,

letting you go.

Three cups today

I fill and drain:

Balls for thought,

heart in the heat.

feet for naught!

NO HISTORYI can barely sketch

the copse of families

from which I grow

and bear these fruit:

thin traceries

from my mother and

my father, which I

scarce heard in passing.

Perhaps it's because I

never meant to have

children; perhaps

it's just the American

way, where family

is a dandelion burst

of white sails in

every direction,

piloted by any random

wind. I can

name my grandparents

and point to their towns

-small house in Cedar

Rapids and Jacksonville.

Therapy has urged me

to exhume my kindred

bones and examine them

with cold eyes; I've seen

shadows of anger and

contempt longer than

my own, and broken

hearts tolling the

years like crimes. Looking

back I see perpetual

family motion,

a throw in reverse

from South to North

and West to East, figures

boarding ships and watching new

worlds shrink along with hope;

a drainage down the tub

toward some ancient arrears,

a story told in thick Scot-Irish

brogue spilling back

into suddenly righted drinking

horns which never could

claim plenty. Still none of this

strikes pay dirt where

this poem yearns: My totems

are real, but I can't name

or know them well enough.

That might explain why there's

never enough money in the bank

or why my need for absence

wants me dead, but not

why the song need fail

upon my lips; nor why

my wife and I live so

many miles apart

from each other that

we now seem partnered

to each other's "No."

My fruits are bittersweet

and pale, glistening

with dew but too far out

to pluck. Saddest of all is

that this way is so common

to us all that tearing down

the orchard after first harvest

seems a virtue. Perhaps

this is just the karma of

the ever-westward nomad

spawned on Indo-European

steppes, a man who not long

ago reached his booming

Pacific and found no more

passage, just a thin,

eternal shore. The only

destiny now ours

repeats its few scarred hours.

GUY'S WALL

GUY'S WALL... Less than a billow of the sea

That at the last do no more roam,

Less than a wave, less than a wave,

This thing that hath no home,

This thing that hath no grave ...

- Fiona MacCleod, "In the Night"

Tonight I sit beneath

a naked mulberry tree

on the stone bench where

Guy's ashes were interred

a quarter century ago.

Long chimes in that

tree knock their sad sweet

bones, while the moon

swings brilliant over all,

though coldly, prowing

across a raw spring night.

Sitting here is a vantage

on the productions

of myth and mystery,

not so much cynical

as peripheral, bluesy,

bittersweet. Age becalms

the spirit's buoyant fire

as surely as death

inks a darker fluid

in the pen, a weight

which does not rise

so readily. I do not mean

to criticize the night:

rather, this seat befits

a threshold half in

wonder while the

other half's cold

with rawer truths.

The bell tower and

standing stones are

all so beautiful, sheeted

as they are in such

blue-white silk-

lovely, yes, even

evanescent, engaged

in one of the oldest,

most fertile dances

the mind can imagine,

can hope, can dream ...

So why then carve a

poem from cold hollows,

brooding over the ashes

of a long-lost, scantily

remembered person I but

briefly called a friend?

Who will know this

bench serves also

as a crypt in

another 25 years?

Who will care? The stones

I sit on which cask

that dark oil

tell me nothing

of the man who once

sat up in the limbs

of this mulberry tree

as the rest of us progressed

below heading for the field,

sending down over us the deep

bass of our childhood God,

reminding-no, telling-us

to be good. The stones cannot

(or won't) explain to me

why Guy died of cancer

before age 30, scant months

after his wife Judy gave birth

to Jennifer. Stones are honest

but most times mute:

And so I must scan

the edges of the far field

where the wood gets darker

and memories are faulty

but a certain truth

can only be found there ...

I knew Guy but a season

two years before he left us all.

He taught me a little about

tuning a piano. One day we

were up in someone's hot

attic sweating under the hood

of an old upright. You have

to feel the pitch, Guy

told me. If you think about

whether the string you've

plucked is sharp or flat,

you'll never get it tuned.

And then he showed

me how, weaving his tuning

hammer up and down

the loom of strings

like a sonorous Thor.

He couldn't really explain

it-never enough for me

to learn-but he always got

it right. And when he

finished he played Billy Joel's

"The Piano Man," grandly,

rolling up and down the keys

with authority, harmonizing

the bent quiver of the piano

to the arrows of that song.

Guy had a frantic pulse

for life, for making everything

count. Some ambivalent

genius drove him to seek

the spirit's moony suburbs

halfway between nirvana

and New Jersey. One night

we walked in the woods

over there smoking pot

and talking New Age

phantasmagoria.

He showed me a railway

tunnel which had

long collapsed. We

crept into that dark

until we came upon

a rubble pile. Anybody

home? He boomed to

the devas on the other side.

Surely we'd manifest

a potato god or the

queen of cherry bloom.

Instead there was a crash

of glass and a terrible,

ball-curdling shriek;

we hauled ass out of there

terrified and giggling,

the air behind us shredded

by the nails of whatever

was and was not back in there.

It really happened, though

I doubt tonight it could have.

Only Guy can concur with me,

and he is in the stone.

Guy argued long that summer

about whether the formal

event we were planning

should be called a party or a festival.

The distinction would decide

how much much booze

would be allowed, and when:

perhaps it was a silly point,

but Guy took it to the lists

as fiercely as he whirled

that tuning hammer. Maybe

he just wanted to win the

argument, but he seemed

struck by a certainty none of

us quite fathomed. I surely

didn't know, just turned 21,

half of my father's making,

half of a something far from home

which strummed its blue guitar.

Guy lost that argument,

at least in the first sense

of things; that hot midsummer

day was the first of many

festivals celebrated here

round and down the years.

We set a wood tripod in

the middle of the field and

laced it round with bright ribbons.

I played guitar and my buddy

Dave mandolin as revelers jigged

their best in clouds of gnats

beneath a feral, summer sun.

What else transpired? Why

does that day dim so fast

and what followed stay in

focus in this sere, cold light?

At dusk we drank May

wine with wild strawberries

up in the house, listening

to Pachelbel's Canon in D.

It was all we thought a festival

should be and none of what

we knew, a culmination of

adjacent, airy enough dreams,

formalized into a dance

beneath the hottest,

brightest light of all. Over

the years the tripod was

replaced by standing stones,

and the festivals got bigger

and somehow sweeter:

equinoxes and solstices,

from Samhain to May Day

and back, attended by hundreds,

each devotee of a different

spectra of our faith:

neo-pagan, neo-Christian,

wiccan, vegan, Buddhist,

tattooist, biker, blancher,

blickerer, blueist, each

blaring their reformed

taboos, bedecked

in robes and wreaths and

and cha-cha-cha tutus.

This place has become

a capital of bucolic

whims whirling round

the eminently silent stone:

But you and I, Guy, we

were there for the first one,

peripheral to what my father made

but central to its darker twin.

For as good as all festivals go,

you had wanted more-

something closer to the

world's more fecund crotch-

and madly, so did I. The day had

been too church-like, too blanched

in that too-bright summer sun.

Two glasses of May wine

couldn't do the job:

Some other, redder impulse

was needed for our fire,

an ire which only could be found

long after the white one

went down. And so a

dissident faction of that festival

drove over to Guy's house

to do the party part,

blasting Bruce Springsteen

on the stereo, pounding

shots of Rebel Yell with

our tall-necked Buds. As we

hooted and hammered

and blasted that party jive,

Guy's brown eyes were like

ebonies of that other music

beyond the ribboned field,

burning, perhaps, with

the soul's pagan fire.

Or maybe it was cancer.

Whatever Guy might say

of that night, or how

I might remember it,

tonight I believe I'd seen

my patient, my dark mentor.

For I wanted more.

And so later that night Guy

passed me to a crazed cousin

who lived in a house

on the Delaware. I don't

remember much of what followed

except she was dark in some

folded-in, sad way, and

that her welcome had

to it a sort of ritual clench,

the birth-grapple of

the dark-hottest booze.

The next day as I made

my retreat - shrill trumpets

of a hangover blaring

in my brain pan -

I looked out a window

on the porch to see

black water flowing

almost under the house.

River house, river

witch, bestowing on

me a dark river's blessing,

carrying me away

at the end of that summer

25 years ago. I was

not ready for the New Age,

not with the big night

music playing so loudly

in my ears. The party kept me

from the festivals for many

years; tonight, again, I

try to return, and end up

here in the borderlands.

I thank you, Guy,

wherever you are among

this night's windy shades,

for teaching me about what's

been tempered between the

two faces of the dance.

We yearn and burn,

our sight is split; the view

can kill us or bless us,

be coffin to our ecstasies

or currah us to shore. I'm

not sure you had a choice,

Guy, but I thank you for

making one possible for me,

your shade my trusty door ...

Yes my friend, tonight things

are good. Before me the pond

stares back at the moon with

its black mirror and the standing

stones choir pale homages

in the field. Up in the house my

father and the others are drinking

a Scotch before heading to the field

to celebrate Wesak, the Buddhist

festival of the high Taurus moon.

Tonight, only a few folks are here

- smaller even than the baker's

dozen of New Age hopefuls

who tried with us to manifest

the sea from a glass of May wine

back in '78-but enough.

For wherever two or more

gather to plead human alms

from immensity, a least

a spark of it wilds through

into the mortal bone.

Soon, Guy, I must go and

join my ragged voice to

that prayer, but before

then I want to tell you a few

things, since it will be awhile

before I sit with you again.

I've heard your daughter is

now out of college and Judy

is happy in her way down

in Miami-No Jersey charms

for her! Second, my wife

and I emerge from our dark

hours slowly, perhaps toward

a happy enough future; my party

now at end, perhaps that

festival can begin. Her cat

Buster died last year but

appeared in a dream, saying,

I'm OK now, just wanted

to let you know I had

a good life but I won't be

coming back again.

-Did you ever let your wife know?

-And finally, my father grouses

at 75 years old that he can't stop

coming back, long after the day

five years ago he was so certain

he would die. In your time

I'm sure that time comes

soon, too very soon.

That's about all. We don't

hardly know how

to tell our stories, Guy,

much less brave an end.

I'm not sure how this poem

will get there. As I listen

to those chimes beating against

each other first calm then wild,

I know they're all I really

have of you. I wish I

could see half of what I

dream is here, but I'm

grateful you and I

remain where we are, citizens

on either side of a stone wall.

As a cold wind blows indifferently

over us, I think of all the others

whose ashes are also buried here -

AIDS victims, earth mamas,

prodigal boys who couldn't quite

get home, my dad's dog Lancelot

beneath a small dolmen next

to the house. There are crypts

beneath the chapel floor

waiting for my father and Fred,

for Albertine who's just entered hospice,

for the hopefully mixed ashes of

my brother and his wife.

There are plenty of memorials

on this land, too, heaps of stones

in the forest, feathers slung

from limbs, trees planted to

grow where we stopped,

like the weeping cherry

put in last week for a young

woman who killed herself.

So many dead limn this land

with you Guy, fading into the

moon-cast shadows of

oblivion, silent witnesses to

the horde of living who come

back every season to beat drums,

swing crystals, and troop the wood

in search of what, I suspect,

only ashes find by scattering.

Some day I'll look into that

bell tower door searching

the space my father departed

through, sniffing for a trace

of Borkum Riff or Scotch whiskey,

straining my eyes for a glint

of his laughing blues.

I suspect I won't see

anything but stones and field

and the wood's black umbers,

all awash in and resonant with

this same old brilliant bonelight.

And I suspect I will say then

to him as I say to you tonight:

friend, fare thee well, the real world

is carved from your strange hallows.

Your music's in my bones.

Play me a song Mister Piano Man,

grandly on the ivories

of those chimes.

Sing to me about the wild

betweens and how to love

the living wonder there. Voices

are now weaving in the bell

tower; the ceremony's

begun. Will you play Buddha

for me tonight, old friend,

high up in that mulberry tree,

and you add your deep voice

to our still-human weave?

Will you bless us with

what you've earned

among the ancient stone?

And will you keep tuning

this heart of mine with

what's strung between

the blood-root of this stone

and the dream which praises all?