waves

waves1981

waves

carry me carry you

to this beach

so frightened

to be so close

to be so completely here with you

the mist is thick around us

I cannot say how I got here

or remember where I came from

it no longer exists

to touch you

our skin skittish as colts

in a storm

and pass through with you

to a place that has no name

that terrible place of rest

between firmaments

where we become one

and sink there

then wake walking on this grey beach,

home at last,

hearing only the crash

of things forgotten long ago:

waves

waves

THE CHILDREN OF WATERFiona MacLeod

"O hide the bitter gifts of our lord Poseidon"

—Archolochus of Paros

… Long ago, when Manannan, the god of wind and sea, offspring of Lir, the Ocearius of the Gael, lay once by weedy shores, he heard a man and a woman talking. The woman was a woman of the sea, and some say that she was a seal: but that is no matter, for it was in the time when the divine race and the human race and the soulless race and the dumb races that are near to man were all one race.

And Manannan heard the man say: "I will give you love and home and peace." The sea-woman listened to that, and said: "And I will bring you the homelessness of the sea, and the peace of the restless wave, and love like the wandering wind." At that the man chided her and said she could be no woman, though she had his love. She laughed, and slid into green water.

Then Manannan took the shape of a youth, and appeared to the man. "You are a strange love for a seawoman," he said: "and why do you go putting your earth-heart to her sea-heart?" The man said he did not know, but that he had no pleasure in looking at women who were all the same.

At that Manannan laughed a low laugh. "Go back," he said, and take one you'll meet singing on the heather. She's white and fair. But because of your lost love in the water, I'll give you a gift."

And with that Manannan took a wave of the sea and threw it into the man's heart. He went back, and wedded, and, when his hour came, he died.

But he, and the children he had, and all the unnumbered clan that came of them, knew by day and by night a love that was tameless and changeable as the wandering wind, and a longing that was unquiet as the restless wave, and the homelessness of the sea. And that is why they are called the Sliochd-na-mara, the clan of the waters, or the Treud-na-thonn, the tribe of the sea-wave.

And of that clan are some who have turned their longing after the wind and wave of the mind--the wind that would overtake the waves of thought and dream, and gather them and lift them into clouds of beauty drifting in the blue glens of the sky.

How are these ever to be satisfied, children of water?

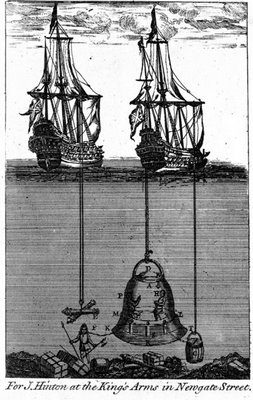

ROGUE WAVE

ROGUE WAVEJuly 12

I.

When a storm hit the cruise

ship Norwegian Dawn on

the morning of April 15, 2005

as it neared the Georgian coast,

the gale was nothing special

for the crew -- bigger waves,

harder winds, just hunker

hunker things down &

serve free drinks in the bar --

so what? Then a rogue wave

seven stories high crashed

into the ship’s bow and raced past

as high as the tenth deck,

smashing window, flooding

many cabins & injuring

four passengers. What the

hell was that? all wondered

as the huge wave thundered

behind and was gone. Once

considered freak appearances,

rogues were classed with mermaids

and sea-beasts in the blue catalogue,

a 10,000-year event in the

early calculations of science.

But recently an increasing

pile of data shows suggests

that freak waves are not

so random and may have

sunk dozens of ships. Scientists now

believe that at any given moment

10 rogues are lumbering the

lanes, each with a theoretical

max height of 198 feet. One

theory says that big waves

form with regularity in those

regions which are swept

by hard currents, like

the Agulhas off South Africa a

nd the Gulf Stream

which sweeps the Bermuda

Triangle. Those currents are

so strong that they can pitch

waves like no other force

in the known world.

Another theory adds

the influence of winds

coming from the other

direction, focussing

sets of waves which become

shorter in the distance

between them and

raising individual peaks.

But how then to predict

their arisings and assault,

providing more safety

to the sea-lanes?

One sure sign is when

disparate trains of

waves come together,

often from different

storms. Sometimes

they meet and cancel

each other out;

but other times

it just makes them

(or one especially)

high and higher,

assuming the dread

tower of the rogue.

So far the predictions

have only been successful

off the coast of South

Africa, but give our

hornrims time, the sea

will become safer,

not for any talent

we have for quelling it,

but rather for seeing

far enough into its

foment to divine which

way it rises and then

steer safely away, as coasts

move inland when

a hurricane whirls

down, and farmers get

five minutes to duck

for cover as a

twister roars on through.

Give them time

and sailing will be

like flying: A known

into which old

fears and longings

still harrow the bone.

(source: “Rogue Giants at

Sea,” William J. Broad,

NY Times, 7/11/06

II.

Yes, I know about when

longing smashes into longing

out on the sea-roads of

the heart and then suddenly

all’s calm: That trope

states that two great

desires can only cancel

each other out, straining

too hard for the beloved

to grasp much more than

shade. But what if

waves sometimes collide to form

immenser waves, desire

upon desire heaved and

smashed against all shores?

That my longing’s

scream was flattened

by the night’s own too-loud

gleam is by now

pro forma in these songs, that rope by

which I’ve hauled

up ten thousand tropes.

I venerate that truth

in a dark place in my

heart, a freezing

cathedral with no

roof where empty

seas crash all night.

But perhaps the

very summa

it arch-icily sustains

is floored by an

a priori smash: One

night long ago

(this lower surge

now croons) I found

both her and something

deeper, as if by

seeing a stranger

standing smiling

in the pot-smoke

of party’s room

I saw the woman

in my dream,

the one who

stood naked

in a river while

salmon swam

up past her feet

and through her

bed-to-bed spread

legs. That sight

unleashed a springtime

mash of waters in

my heart, turbbined

by the faintest welcome

in a smile which arced

from party to my bed

where Yes and Yes freaked

the big one, numen

enough (though

I was too young

and greedy to know

it false) to make that

night the wave I’m riding

still in yee-haw bliss

toward all divinely

naked shores. It had

to happen between

me and a her

but not more than

as the surficial key

which unlocked the

my bedded heart,

freeing chamber

to welcome chamber

and rouse and

awful crest whose

magnitude and art

has so far flattened

all comers from without,

even as it waits

in the frozen silence

of longing’s without,

praying and nailing me

to that broken altar

in a ruined chapel

at the bottom of

all seas. For years

I thought my life

was shaped by

two or three rogue

waves which

smashed me

utterly -- a handful

of wild nights

which ebbed to

clear blue drifting

dawns -- but now

I suspect each

vigil here is

productive of a

rogue, incanted and

decanted as the

lines smash hard

against the heart

which loves so much

to read ‘em. See,

this poem’s a mile

high, malefic black

and green up seven

pages of majesty

and mystery, mockery too,

these words pale shouts

into the awesome bassos

of wildly surging seas.

And like blue balls

which cannot hold back

their gouts of lava

ache, I’m desperate

here to find a shore

to loose this monster’s

roar: But where? This

reach of white will have

to do, a snatch of welcome

spread and juiced and

crying for swole depths

of my heart-crazed,

wild Yes: Here’s all my

hell’s brute smash and

thunder, foam wild as

geysered sex or the

spoutings of the whale

who blows this hand across

the page and then dives

back into the gloom of

silence, already hunting

for tomorrow’s song

amid the ribs of

whalers and the

lost bell of my

longing, right here,

forever there.

CLIODNA’S WAVE

CLIODNA’S WAVEAND it was in the time of the Fianna of Ireland that Ciabban of the Curling Hair, the king of Ulster's son, went to Manannan's country.

Ciabhan now was the most beautiful of the young men of the world at that time, and he was as far beyond all other kings' sons as the moon is beyond the stars. And Finn liked him well, but the rest of the Fianna got to be tired of him because there was not a woman of their women, wed or unwed, but gave him her love. And Finn had to send him away at the last, for he was in dread of the men of the Fianna because of the greatness of their jealousy.

So Ciabhan went on till he came to the Strand of the Cairn, that is called now the Strand of the Strong Man, between Dun Sobairce and the sea. And there he saw a curragh, and it having a narrow stern of copper. And Ciabhan got into the curragh, and his people said: "Is it to leave Ireland you have a mind, Ciabhan?" "It is indeed," he said, "for in Ireland I get neither shelter nor protection." He bade farewell to his people then, and he left them very sorrowful after him, for to part with him was like the parting of life from the body.

And Ciabhan went on in the curragh, and great white shouting waves rose up about him, every one of them the size of a mountain; and the beautiful speckled salmon that are used to stop in the sand and the shingle rose up to the sides of the curragh, till great dread came on Ciabhan, and he said: "By my word, if it was on land I was I could make a better fight for myself."

And he was in this danger till he saw a rider coming towards him on a dark grey horse having a golden bridle, and he would be under the sea for the length of nine waves, and he would rise with the tenth wave, and no wet on him at all. And he said: "What reward would you give to whoever would bring you out of this great danger?" "Is there anything in my hand worth offering you?" said Ciabhan. "There is," said the rider, "that you would give your service to whoever would give you his help." Ciabhan agreed to that, and he put his hand into the rider's hand.

With that the rider drew him on to the horse, and the curragh came on beside them till they reached to the shore of Tir Tairngaire, the Land of Promise, They got off the horse there, and came to Loch Luchra, the Lake of the Dwarfs, and to Manannan's city, and a feast was after being made ready there, and comely serving-boys were going round with smooth horns, and playing on sweet-sounding harps till the whole house was filled with the music.

Then there came in clowns, long-snouted, long-heeled, lean and bald and red, that used to be doing tricks in Manannan's house. And one of these tricks was, a man of them to take nine straight willow rods, and to throw them up to the rafters of the house, and to catch them again as they came down, and he standing on one leg, and having but one hand free. And they thought no one could do that trick but themselves, and they were used to ask strangers to do it, the way they could see them fail.

So this night when one of them had done the trick, he came up to Ciabhan, that was beyond all the Men of Dea or the Sons of the Gael that were in the house, in shape and in walk and in name, and be put the nine rods in his hand. And Ciabhan stood up and be did the feat before them all, the same as if he had never learned to do any other thing.

Now Gebann, that was a chief Druid in Manannan's country, had a daughter, Cliodna of the Fair Hair, that had never given her love to any man. But when she saw Ciabhan she gave him her love, and she agreed to go away with him on the morrow.

And they went down to the landing-place and got into a curragh, and they went on till they came to Teite's Strand in the southern part of Ireland. It was from Teite Brec the Freckled the strand got its name, that went there one time for a wave game, and three times fifty young girls with her, and they were all drowned in that place. And as to Ciabban, he came on shore, and went looking for deer, as was right, under the thick branches of the wood; and he left the young girl in the boat on the strand.

But the people of Manannan's house came after them, having forty ships. And Iuchnu, that was in the curragh with Cliodna, did treachery, and he played music to her till she lay down in the boat and fell asleep. And then a great wave came up on the strand and swept her away.

And the wave got its name from Cliodna of the Fair Hair, that will be long remembered.

LONGING

LONGING2002

I sometimes wonder whether longing

can’t radiate out from someone so

powerfully, like a storm, that nothing

can come to him from the opposite

direction. Perhaps William Blake

has somewhere drawn that— Rilke, letter, 1912

There is a longing in us which

grows from sigh to starry shriek.

Perhaps comets are charred furies

of that pain, a whirl of frozen fire

which ghostlike tears to God’s porch

and back, insatiable and unanswered.

Perhaps. All I know is that

it’s infinitely perilous to think

that longing has a human end.

In my cups I once believed

a woman mooned for me,

her longing a white welcome

over my million nights alone.

I met and passed her many times

those hard years, blinded by the aura

of her unvowled name.

Surely when two longings touch

it’s like when great waves collide,

the wild sea witched flat.

Our deeper thirst can never sate:

as each draught of booze

was never enough, so each

embrace tides a milkier door.

I recall a young man

walking home drunk on a

frozen night long ago,

his beloved nowhere

to be found in the chalice

he had named. Winds hurled

steel axes through the

Western sky, failing to clear

the cruel foliage of fate.

In his defeat he was greater

than any angel beckoned

by that night: his heart so

hollowed by longing

as to chance in pure cathedral,

her absence the clabber of a bell

shattering the frozen air,

trebling the moon

without troubling a sound.

FREEZE FRAMEfrom “A Breviary of

Guitars,” late June 2000

What was so arid

in a hammerlock

of high pressure

and a triumphant

angel sun now

just foams &

spouts in storm

after storm:

Every day now

I drive in to

work & see

bump marble

rumps mooning

the heavens:

By lunch they’re

massed ever

empurpled with

fevers hurling

ejaculate snaps

& flooding the

streets: Like new

lovers who cannot

exhaust their

bottomless cistern

of desire hurling

their bodies

at each other

frantic to find

what screams for

release: Storms

again midafternoon

as the day’s

wearies settle

amid problem

accounts & new

AS400 system

woes & programming

patches & the

itch & flick of

a desire which

has no body

it can vanquish

in: But man

it rains hard

a ballsoaking

cuntslobbering

titheave

ballstothewalls

of a storm

in which the

green world

shouts glittery

arias of joy:

The last time

such storm

rose in me

with Donna

was a wan

fair Sunday in

November ‘85

when we drove

to New Smyrna

Beach with her

son Nicky packing

lunch & a bottle

of sherry: Parked

along a deserted

stretch & set

a blanket on

the sand & lounged

there a couple

of hours enjoying

80 degree temps

& the sun

mellow and

sweet & the

surf softly

slapping and

slushing, love

not yet ebbed

& loss early

in its flow: Donna

just beautiful

in a black one

piece bathing

suit that carved

her curves with

authority &

grace & surrender

& her skin a

shock of white

as when she

first peeled

down her panties

for me then

turned her

ass toward my

bright hungry ache:

We sipped our

sherry watching

Nicky play

with a truck

in the sand &

Mr. Mister’s

“Run to Her”

on my boombox

half lost to

the sound of that

swoony merciless

surf: Blue pale

sky, blue green

waters stretching

for miles &

Donna’s eyes

sad and distant,

looking past me:

She got up and

walked down to

to the water’s

edge for a while

soaking up

all that feral

eternity that

makes babies

love & graves

her back to me

as one passing

through a door

into silence:

And then turned

to smile at

me radiant with

all I’ve ever

desired rising

in my heart

like Venus on

the half shell

amid the foam

of my balls &

then looking for

one second like

another woman

on another beach

in another love

which ended

in another surf

& I felt then

the horrid ironic

fatefulness

of the Ocean,

a wave which

parts the thighs

of a love which

births departure:

But Donna

just smiled

bittersweetly and

then as if she

had come to

a decision walked

back and gathered

up Nicky and

put him in

her car telling

him to sleep:

For a few minutes

the boy’s face

(resembling Donna

in the eyes

but the rest

a cipher of

some other man’s

love) crying in

the window but

Donna was

unmoved &

the head slowly

disappeared

like a setting

sun into silence:

Donna then looked

over at me

& smiled the way

she did that night

up at Fern Park

Station & then

lowered her

body on mine

to kiss me full

and dreamy

as the sea her

body breathing

full against mine

like a surf &

her bones against

my bones as

close as bones

go: Kissed slowly

down my chest

in a wave &

gripped my trunks

with both hands

& then pulled

them down far

enough to take

my startled cock

in her mouth

& slowly, sweetly,

gently, deeply

suck that slender

isthmus of flesh

that separates

I and Thou:

Loving there

what’s impossible

to find and

perilous to forget:

I watched her

for a while glide

up and down

my cock with

slow sure strokes

her mouth a

firm clench on

my slick hardening

length, veins there

pumping out like

clouds rising

over the sea

& her eyes closed

maybe prayerfully

or brokenly or

already somewhere

else — who knows:

Her long dark

blonde hair falling

around her pistoning

mouth like

a waterfall & each

downward stroke

washing me in

that gorgeous sure

river or wave

I always felt

in the sex that

joined Donna

to me: Then I

closed my eyes

& lay back

surrendering to

the pleasure

slowly building

in me, so sweet

& watery, not

urgent in the

way of new lovers

or knowledgeable

or secure like

old lovers: Rather

we were as

one receiving

a last kiss from

waters now receding:

Oh drifting boat

on sunny waters

on God’s now

gorgeous earth,

a breeze softly

raking the

glittery soft surf

& Donna’s hand

now cupping my

balls squeezing

& gently milking

the dangerous

seed rising up

there as she

settles her mouth

all the way

down to my

pubic bone &

I’m coming, coming,

rising up in

a wave of white

screaming joy

and she doesn’t

let go but takes

all of me in,

drinks my salty

sticky seed &

it feels so

strange so

utterly fucking

sweet as if

my balls were

dissolving & the

rest of me to

in this tingling

toe twitching

exhalation

emptying

erasing &

killing my

every conflicted

motion: O stay

there for just

a little while,

Breviary — linger

in the lavish

mouth which swallows

me whole: a

mother’s mouth

giving suck &

a receiving back

the milk she

gave me: The

ocean stretching

like a blue gray

angel’s blessing

& “Broken Wings”

on the blaster

true just for those

seconds and

so eternally true:

All the futile

stupid arrogant

wrongheaded

cruel self

destructive

things I wreaked

with that white

boy’s penis

absolved in

that melting

molten spasm:

These million

words flocking

in the wild sperm

cells flocking

to no home

down her throat

just like the

sea welcomes

no home I

have ever built:

One of my

hands inside

her bathing suit

clutching a

breast squeezing

up a nipple

desperate never

to let go:

This gloriously

beautiful ocean

of an angel

of a woman

nursing my

dolphin on the

wave it still

rides: O crest

& dissolve and

there’s no

way to remain

right there, no

way to prevent

the day’s return

into slow focus,

Donna letting

go with her

mouth kissing

the tip of my

glistening cock

& pulling my

shorts back

up with a sigh

patting my cock

and nuts one

one one one

one one one

one one one

final time: Wipes

her mouth with

her hand her

eyes slowly

refocusing taking

aim again beyond

me: I lift

up on an elbow

& try to push

her down to

kiss, return the

favor by lapping

away at her

sweet milky

thighs but she

shakes her head

sad and firm

& takes a drink

of wine instead

& looks farther

out to a sea

already gone:

O lift up from

that beach O

falcon o sad

sea eagle up

up over to

the edge of that

one infinite

spasm that

crashed up out

of me and through

me at the

same time like

the wave of

the woman of

the sea anointing

& cursing

me like that

baptismal wave

that crested

over me at 14:

Rise up over

the ocean’s

suck & haul

o angel of

my eternally

misbegotten love:

Up over the

rim of the green

ocean and up

up through the

blue heavens:

Up over the

hurl of this

ancient song:

Can you take

me higher o

peregrine

falcon up

where only

blind men see:

Up over the

edge of

my ruination

at your altar

o dolphin muse:

Join me with

my aborted

children, my

daughters of

Neptune: Can

you fly me up

over all to this

warm place

where my seed

lays waiting for

your welcoming

egg in the

belly of all

dead loves: Donna’s

son begins

crying in the

car & she

goes to retrieve

him & we start

packing up

to go: “Run

to Her” on the

blaster already

ironic and Donna

asks me

irritably hey

isn’t there anything

else you can

play? Something

that

rocks?  THE FLOOD

THE FLOOD2000

Your house by the sea

is not a married one.

You are lonely for your wife

remembering how soft

and open she sleeps,

her pale body curving

and falling around

a green silk nightdress.

There is a girl inside

that woman damaged

perhaps too much

by your careens.

Your heart breaks

thinking of her

and so you call her

saying, I’m coming home.

She does not respond,

her silence both still

and oceanic.

You head to the

bedroom to start

packing a suitcase

when you notice

sea-water mashed

against the window

and rising fast.

Safe where you are

but desperate to

go home to her

you chance the door.

Cold water falls

down on you

in a thundering cascade.

You think you

will drown but in the

next scene you stand

in a room harrowed

but dry: The couch

and table with its

telephone just

the way you

remembered them

from the day before

when all was well

but now ruined and

dangerous to touch.

It is a room haunted

by its drowning

unliveable and fell.

You wake with a

start to a ringing

telephone. Your wife now

hates you for what

you let in that door

trying to get back to her.

WAVE WILDERNESS

WAVE WILDERNESS2001

Witness a wide

virago of water:

One wave rising

to engulf a city.

I return here

at the end of a dream,

neither angry nor

afraid, simply ending

at this beach

from the rag

ends of another

ragged night, drunk,

dreary, my

lust a futile,

laughable thing ...

Return to this

beach soon annihilate

in the majesty of

that steel water,

reclaiming at

last this syzygy

of psalms: Bereave

me here, my

children, my poems:

Into that wave

I cast my book:

WIND ON WATER

WIND ON WATERJuly 13

I hear words rising in my

heart’s thought and write

them down, as wind breathes

waves on water, as spirit

billows the sails of day

to ache our arch perfections.

Who knows how far these

rollers will go, or what

shores they’ll rise and

crash against in metronymic

sets of roared silence,

the unsaid said at last

and freed to hoove the next?

Think of the seven seas’

incessant toil and these

daily jaunts of words

on paper make blue sense,

though inland on dry

ground both seem like

a puerile waste

of ink and water,

so much fraught tillage

forever scythed away

with each wave’s fold

and crash. For eons

the human task

was to subdue the world

with mastery of tool

and word: But anyone

who attempts to

cross the sea or build

a fortress on its shore

soon learns that

mother always wins

her doubting dumbass

children back and

sweeps their alms away

in a lush blue swell

bound straight for hell.

Having learned

I can’t beat her (oh

that sea of instructive

deadly nights!), I

turned to join her fray,

becoming the sea’s

own chantey, praising

in this lost and outre

way the strolling

wave which curves

so much like her

that to sing of waves

is to nurse on her

and plunge her every

surf and remit all

urgencies in the crash

and dash and scatter of

divinely foaming milk.

I breathe slow and measured

on the page the claw

and sphincter of God’s

rage so each wave is

laced with gysms too hot

and frenzied for a name,

offering sperm saddle

for the nymph who

choirs astride my hips

as I cross the seas to

hurl my half of Him in Her.

Can you hear the

thrashing of first cold seas

in the dropped shell

of Her surf, the one

I soon leave behind

for days to grind to sand?

Do you hear

those sighs which

enclosed my tensed

collapsing thighs?

Eternal pause of all that

wind on water, my

words upon this page,

my breath slowing at her

neck as we drift now

off to sleep into the

sea’s own clear blue space

inside the bottle

I can’t drink without

drowning in its dregs,

this poem a tiny slip

of paper rolled and

tucked into the hold

of a ship fit in that

bottle’s reach,

a ship whose nippled

masthead begs

to be loosed inside

the marges of your

ears: And all of

whispering in this

tossed mouth’s

ebbing surf,

We are here ...

Are you there?

We are here ...

Do you dare?THE NINTH WAVEFiona McLeod

... On the last Sabbath, old McAlpin had held a prayer-meeting in his little house in the " street," in Balliemore of Iona. At the end of his discourse he told his hearers that the voice of God was terrible only to the evil-doer but beautiful to the righteous man, and that this voice was even now among them, speaking in a thousand ways and yet in one way. And at this moment, that elfin granddaughter of his, who was in the byre close by, let go upon the pipes with so long and weary a whine that the collies by the fire whimpered, and would have howled outright but for the Word of God that still lay open on the big stool in front of old Peter. For it was in this way that the dogs knew when the Sabbath readings were over; and there was not one that would dare to bark or howl, much less rise and go out, till the Book was closed with a loud, solemn bang. Well, again and again that weary quavering moan went up and down the room, till even old McAlpin smiled, though he was fair angry with Elsie. But he made the sign of silence, and began: " My brethren, even in this trial it may be the Almighty has a message for us " --when at that moment Elsie was kicked by a cow, and fell against the board with the pipes, and squeezed out so wild a wail that McAlpin, started up and cried, in the Lowland way that he had won out of his wife, "Hoots, havers, an' a! come oot o' that, ye Deil's spunkie!"

So it was this memory that made Padruig and Ivor smile. Suddenly Ivor, began with a long rising and falling cadence, an old Gaelic rune of the Faring of the Tide.

Athair, A mhic, A Spioraid Naoimh,

Biodh an Tri-aon leinn, a la's a dh'oidhche;

S'air, chul nan tonn, no air thaobh nam beann!

O Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,

Be the Three-in-One with us day and night,

On the crested wave, when waves run high!

And out of the place in the West

Where Tir-nan-Og, the Land of Youth

Is, the Land of Youth everlasting,

Send the great Tide that carries the sea-weed

And brings the birds, out of the North:

And bid it wind as a snake through the bracken,

As a great snake through the heather of the sea,

The fair blooming heather of the sunlit sea.

And may it bring the fish to our nets,

And the great fish to our lines:

And may it sweep away the sea-hounds

That devour the herring:

And may it drown the heavy pollack

That respect not our nets

But fall into and tear them and ruin them wholly.

And may I, or any that is of my blood,

Behold not the Wave-Haunter who comes in with the Tide,

Or the Maighdeann-màra who broods in the shallows,

Where the sea-caves are, in the ebb:

And fair may my fishing be, and the of those near to me,

And good may this Tide be, and good may it bring:

And may there be no calling in the Flow, this Srùthmàra,

And may there be no burden in the Ebb! Ochone!

An ainm an Athar, s'an Mhic, s' an Spioraid Naoimh, Biodh an Tri-aon leinn, a la's a dh' oidhche,

S'air chul nan tonn, no air thaobh nam beann!

Ochone! arone!

Both men sang the closing lines with loudly swelling voices and with a wailing fervour which no words of mine could convey.

Runes of this kind prevail all over the isles, from the Butt of Lewis to the Rhinns of Islay: identical in spirit, though varying in lines and phrases, according to the mood and temperament of the rannaiche or singer, the local or peculiar physiognomy of nature, the instinctive yielding to hereditary wonder-words, and other compelling circumstances of the outer and inner life. Almost needless to say, the sea-maid or sea-witch and the Wave-Haunter occur in many of those wild runes, particularly in those that are impromptu. In the Outer Hebrides, the runes are wild natural hymns rather than Pagan chants; though marked distinctions prevail there also-for in Harris and the Lews the folk are Protestant almost to a man, while in Benbecula and the Southern Hebrides the Catholics are in a like ascendancy. But all are at one in the common Brotherhood of Sorrow.

The only lines in Ivor McLean's wailing song which puzzled me were the two last which came before "the good words," in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit," etc.

"Tell me, in English, Ivor," I said, after a silence, wherein I pondered the Gaelic words, " what is the meaning of--

'And may there be no calling in the Flow, this Srùthmàra,

And may there be no burden in the Ebb?'"

" Yes, I will be telling you what is the meaning of that. When the great tide that wells out of the hollow of the sea, and sweeps toward all the coasts of the world, first stirs, when she will be knowing that the Ebb is not any more moving at all, she sends out nine long waves. And I will be forgetting what these waves are: but one will be to shepherd the sea-weed that is for the blessing of man, and another is for to wake the fish that sleep in the deeps, and another is for this, and another will be for that, and the seventh is to rouse the Wave-Haunter and all the creatures of the water that fear and bate man, and the eighth no man knows, though the priests say it is to carry the Whisper of Mary, and the ninth--"

" And the ninth, Ivor?"

" May it be far from us, from you and from me and from those of us! An' I will be sayin' nothing against it, not I; nor against anything that is in the sea! An' you will be noting that!

" Well, this ninth wave goes through the water on the forehead of the tide. An' wherever it will be going it calls. An' the call of it is, ' Come away, come away, the sea waits! Follow! . . . Come away, come away, the sea waits! Follow!'

An' whoever hears that must arise and go, whether he be fish or pollack, or seal or otter, or great skua or small tern, or bird or beast ofthe shore, or bird or beast of the sea, or whether it be man or woman or child, or any of the others."

" Any of the others, Ivor? "

" I will not be saying anything about that," replied McLean, gravely; " you will be knowing well what I mean, and if you do not it is not for me to talk of that which is not to be talked about.

[1 Ivor, of course, gave these words in the Gaelic, the sound of which has the strange wail of the sea in it.]

" Well, as I was for saying: that calling of the ninth wave of the Tide is what Ian-Mòr of the hill speaks of as 'the whisper of the snow that falls on the hair, the whisper of the frost that lies on the cold face of him that will never be waking again."'

" Death? "

" It is you that will be saying it.

" Well," he resumed after a moment's hush, " a man may live by the sea for five score years and never hear that ninth wave call in any Srùth-màra, but soon or late he will bear it. An' many is the Flood that will be silent for all of us: but there will be one Flood for each of us that will be a dreadful Voice, a voice of terror and of dreadfulness. And whoever hears that Voice, he for sure will be the burden in the Ebb."

" Has any heard that Voice, and lived?

McLean looked at me, but said nothing. Padruig Macrae rose, tautened a rope, and made a sign to me to put the helm alee. Then, looking into the green water slipping by--for the tide was feeling our keel, and a stronger breath from the sea lay against the hollow that was growing in the sail--he said to Ivor:

"You should be telling her of Ivor MacIvor mhic Niall."

"Who was Ivor MacNeil?" I said.

"He was the father of my mother," answered McLean, " and was known throughout the north isles as Ivor Carminish, for he had a farm on the eastern lands of Carminish which lie between the hills called Strondeval and Rondeval, that are in the far south of the northern Hebrides, and near what will be known to you as the Obb of Harris.

" And I will now be telling you about him in the Gaelic, for it is more easy to me, and more pleasant for us all.

" When Ivor MacEachainn Carminish, that was Ivor's father, died, he left the farm to his elder son and to his second son, Seumas. By this time, Ivor was married, and had the daughter who is my mother. But he was a lonely man, and an islesman to the heart's core. So . . . but you will be knowing the isles that lie off the Obb of Harris-the Saghay, and Ensay, and Killegray, and farther west, Berneray and, north-west, Pabaidh, and beyond that again, Shillaidh? "

For the moment I was confused, for these names are so common: and I was thinking of the big isle of Berneray that lies in huge Loch Roag that has swallowed so great a mouthful of Western Lewis, to the seaward of which also are the two Pabbays, Pabaidh Mòr and Pabaidh Beag. But when McLean added," and other isles of the Caolas Harrish " (the Sound of Harris), I remembered aright; and indeed I knew both, though the nor' isles better, for I had lived near Callernish on the inner waters of Roag.

" Well, Carminish had sheep-runs upon some of these. One summer the gloom came upon him, and he left Seumas to take care of the farm and of Morag his wife, and of Sheen their daughter; and he went to live upon Pabbay, near the old castle that is by the Rua Dune on the southeast of the isle. There he stayed for three months. But on the last night of each month he heard the sea calling in his sleep; and what he heard was like 'Come away, come away, the sea waits! Follow . . . Come away, co e away, the sea waits! Follow!' And he knew the voice of the ninth wave; and that it would not be there in the darkness of sleep if it were not already moving toward him through the dark ways of An Dàn (Destiny). So, thinking to pass away from a place doomed for him, and that he might be safe elsewhere, he sailed north to a kinsman's croft on Aird-Vanish in the island of Taransay. But at the end of that month he heard in his sleep the noise of tidal waters, and at the gathering of the ebb he heard

' Come away, come away, the sea waits! Follow!' Then once more, when the November heat-spell had come, he sailed farther northward still. He stopped a while at Eilean Mhealastaidh, which is under the morning shadow of high Griomabhal on the mainland, and at other places, till he settled, in the third week, at his cousin Eachainn MacEachainn's bothy, near Callernish, where the Great Stones of old stand by the sea, and hear nothing forever but the noise of the waves of the North Sea and the cry of the sea-wind.

" And when the last night of November had come and gone, and he had heard in his sleep no calling of the ninth wave of the Flowing Tide, he took heart of grace. All through that next day he went in peace. Eachainn wondered often with slant eyes when he saw the morose man smile, and heard his silence give way now and again to a short, mirthless laugh.

" The two were at the porridge, and Eachainn was muttering his Buich-eas dha'it Ti, the Thanks to the Being, when Carminish suddenly leaped to his feet, and, with white face, stood shaking like a rope in the wind.

" ' In the name of the Son, what is it, Ivor mhic Ivor? What is it, Carminish?' cried Eachainn..

" But the stricken man could scarce speak. At last, with a long sigh, he turned and looked at his kinsman, and that look went down into the shivering heart like the polar wind into a crofter's hut.

" ' What will be that? ' said Carminish, in a hoarse whisper.

" Eachainn listened, but he could hear no wailing beann-sith, no unwonted sound.

" ' Sure, I hear nothing but the wind moaning through the Great Stones, an' beyond them the noise of the Flowin' Tide. '

" ' The Flowing Tide! The Flowing Tide! ' cried Carminish, and no longer with the hush in the voice. 'An' what is it you hear in the Flowing Tide?'

" Eachainn looked in silence. What was the thing he could say? For now he knew.

" Ah, och, och, ochone, you may well sigh, Eachainn mhic Eachainn! For the ninth wave o' the Flowing Tide is coming out o' the North Sea upon this shore, an' already I can hear it calling, ' Come away, come away, the sea waits! Follow! . . . Come away, come away, the sea waits! Follow!'

And with that Carminish dashed out the light that was upon the table, and leaped upon Eachainn, and dinged him to the floor and would have killed him but for the growing noise of the sea beyond the Stannin' Stones o' Callanish, and the woe-weary sough o' the wind, an' the calling, calling, 'Come, come away! Come, come away!'

" And so he rose and staggered to the door, and flung himself out into the night, while Eachainn lay upon the floor and gasped for breath, and then crawled to his knees, an' took the Book from the shelf by his fern-straw mattress, an' put his cheek against it, an' moaned to God, an' cried like a child for the doom that was upon Ivor Maclvor mhic Niall, who was of his own blood, and his own fosterbrother at that.

" And while he moaned, Carminish was stalking through the great, gaunt, looming Stones of the Druids, that were here before St. Colum and his Shona came, and laughing wild. And all the time the tide was coming in, and the tide and the deep sea and the waves of the shore and the wind in the salt grass and the weary reeds and the black-pool gale made a noise of a dreadful hymn, that was the death-hymn, the going-rune, of Ivor the son of Ivor of the kindred of Niall.

" And it was there that they found his body in the grey dawn, wet and stiff with the salt ooze. For the soul that was in him had heard the call of the ninth wave that was for him. So, and may the Being keep back that hour for us, there was a burden upon that Ebb on the morning of that day.

" Also, there is this thing for the hearing. In the dim dark before the curlew cried at dawn, Eachainn heard a voice about the house, a voice going like a thing blind and baffled,

'Cha till, cha till, cha till mi tuille!

I return, I return, I return never more!

--from The Works of Fiona McLeod, Volume II

WAVE RAVE

WAVE RAVEfrom "A Breviary of

Guitars," 2000

The present/

Autumn 1985:

The wave the sea

woman dashed

on me in the

welcome of

a few melusines

has baptized me

into a curve

and curl, an

arch foam

ache and break:

I accept today

that such loves

may have only

been moonbeams,

faulty ego

boundaries &

juvenile whim:

But the wave

itself is

one of the greater

angels, a titanic

motion swelling

up to kiss the

moon: One night

many years later

I walked Cocoa

Beach with a

woman Donna’s

age long after

Donna swam away:

A full moon

high above a

surf impossibly

stirred by a

hurricane

200 miles

out to sea; Waves

like we had

never seen at

that timid beach

scrolling in

huge dark swells

& the smash

& hiss of surf

a dull pounding

blissful roar:

Silver milk

in those waves

poured from

a crazy moon

& a stiff warm

breeze blowing

through the desire

we felt for each

other but could

not, would not

touch for the ties

she kept with

another: A

dazzling night

in which we

were gifted

with a sea so

few would ever

see: Some time

after midnight

on that silvered

beach where

angels sang

brokenly & eternally

of desire and its

terrible torn

beauty we stopped

talking & listened

& looked

& touched each

other’s hand, just

once, hugged,

just once, kissed

for a second then

turned to go:

I wrote a poem

on it and later

set the night

to music on

a keyboard

synthesizer (no

guitar could

suffice, I’ve learned)

tolling these

slow sure chords,

Emaj7 - Cmin7

F#min7 - Amaj7,

composing wave

after wave

of basso bellows

& swelling strings

& dazed dreamy

overtones caught

in the suck and

the roar of

a remembered night:

O I’m still

desperate to

describe the wave

of the sea woman

rising in me

in you impossibly

high fraught

with the ache

and plunge of

perfect union,

sure in its

rhythm & pulse

& chording &

broken utterly

when cusp trembles

foams & turns

down at the

moment of coming

falling weightless

for aeons in a

sheer glass curve

collapsing in a

smash and a

roar into oblivion:

I’m 43 now

and doubt

any such wave

does more than

shipwreck &

estrange us from

all we build and

strive for in

such difficulty:

No marriage

abides by such

a wave, no

poems or songs

ever summon

it truly back &

it’s an utterly

selfish amoral

unworthy

unwholesome

surrender no

one else in the

world gives

one tiny turd for:

Yet I desired

her & she kissed

me with that wave

& I can’t stop

this furious scrawl

down the page

mounting this

babel of joy:

Yesterday in

the spinning class

the instructor

was both lovely

& cruel, asking

us to pedal

harder faster up

an impossible

slope: It was

then that I truly

saw the wave I here

praise, this fearsome

nor’easter of a

swell curving

up high high

and higher,

mountainous to

moon: Oh

the teacher was

almost beyond

my heart & I

almost gave out

toward the end,

staying in gear

12 while she called

out 13, 14, 15:

She finally let

us go to

downshift &

pedal mad down

the hill & then

slow & slow

& slow till we

pedalled air

in sleepy arcs:

Of course she’s

this muse that

sirens me out

of too little

sleep & then swims

out just beyond

the tip of this

pen singing, “Come—”:

She was in the

3 or 4 women

who for whatever

reasons undressed

me in her waters

& then drowned me:

She stands beside

the real women

I have actually

loved judging their

passions which

always melt

into a deeper

surer love &

flashes her

booty whispering

“you could have

chosen

this, you

know”: I cannot

surrender to

her but I will

not let her go:

Blue green monster

rising sinister

& ecstatic toward

a shore of loins

my balls throb

and pulse for

desperate for just

one smooch of

that hopeless

homeless hocus

hooch of

coochie coo

invoked in this

Breviary, this

blue green wave

reaching for

a fruit I can

never reach,

never burst, till

death do I

truly die: Such

is the passionate

singing I can

no more forget

than the sea

can reclaim it’s

orphaned moon:

Ah desperate

I am this morning

stung and dazed

by the foam of

one wave so

fucking long ago

rising anew here:

And I’m judged

as unworthy now

as I was then:

My hands weary

& aching & tingling

& the loam of

pages fattening

into a mound,

a mountain,

a sea, a cosmos

in the hollows

of a conch, a

pale flickering

dream at the

end of a farewell

& still I can’t

name it or

claim it

nor most of

all let it go:

The woman

of the sea has

exactly what

she wished: And

I her wandering

wounded dolphin

surfer watch the

horizon and wait

for the waters to

heave the next

slow swelling chord: