Harm and Boon

A WALK BLOSSOMING

Jack Gilbert

The spirit opens as life closes down.

Tries to frame the size of whatever God is.

Finds that dying makes us visible.

Realizes we must get to the loin of that

before time is over. The part of which

we are the wall around. Not the good or evil,

neither death nor afterlife but the importance

of what we contain meanwhile. (He walks along

remembering, biting into beauty,

the heart eating into the naked spirit.)

The body is a major nation, the mind is a gift.

Together they define substantiality.

The spirit can know the Lord as a flavor

rather than power. The soul is ambitious

for what is invisible. Hungers for sacrament

that is both spirit and flesh. And neither.

-- from Refusing Heaven (2005)

***

The lifelessness, the hopelessness, the despair of the winter sea are an illusion. Everywhere there are assurances that the cycle has come to the full, containing the means of its own renewal. There is the promise of a new spring in which the very iciness of the winter sea, in the chilling of the water, which must, before many weeks, become so heavy that it will plunge downward, precipitating the overturn that is the first act in the drama of spring. There is the promise of new life in the small plantlike things that cling to the rocks of the underlying bottom, the almost formless polyps from which, in spring, a new generation of jellyfish will bud off and rise into the surface waters. There is unconscious purpose in the sluggish forms of the copepods hibernating on the bottom, safe from the surface storms, life sustained in their tiny bodies by the extra store of fat with which they went into this winter sleep.

-- Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

APOSTROPHE (2)

May 5

Winter or summer She has her

Ways with me, gestating songs

Equally in the turning year,

Freezing me in winter seas

Then soaring me in the

Blare of near-nude beaches.

Either way she bids me sing

And it’s the same baritone,

Joy and woe perfecting

The heart in the next way

Of desires unknown even

To itself. I pet our cat Red

On the back porch at dusk

And he purrs richly in my lap,

As hungry for love as he is

Later fro whatever prey he

Tears in our nearly dark

Back yard, a lover at next work.

(Apostrophe: 2. The arrangement of chloroplasts

along the lateral walls of leaf cells -- called positive

when caused by intense light and negative

when caused by prolonged darkness.)

HARM AND BOON IN THE MEETINGS

Jack Gilbert

We think the fire eats the wood.

We are wrong. The wood reaches out

to the flame. The fire licks at

what the wood harbors, and the wood

gives itself away to that intimacy,

the manner in which we and the world

meet each new day. Harm and boon

in the meetings. As heart meets what

is not heart, the way the spirit

encounters the flesh and the mouth meets

the foreignness in another mouth. We stand

looking at the ruin of our garden

in the early dark of November, hearing crows

go over while the first snow shines coldly

everywhere. Grief makes the heart

apparent as much as sudden happiness can.

-- from The Great Fires (1995)

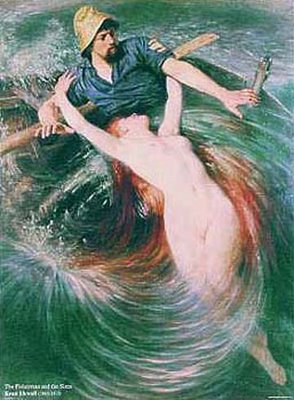

NEIL MC CODRUM AND THE SELKIE

Long ago, on an island at the northern edge of the world, there lived a fisherman called Neil McCodrum. He lived all alone in a stone croft where the moorland meets the shore, with nothing but the guillemots for company and the stirring of the sand among the shingle for song.

But in the long winter evenings he would sit by the peat-fire and watch the blue smoke curling up to the roof, and his eyes looked far and far away as if he was looking into another country. And sometimes, when the wind rustled the bent-grass on the machair, he seemed to hear a soft voice sighing his name.

One spring evening, the men of the clachan were bringing their boats full of herring into shore. They swung homeward with glad hearts, and their wives lit the rushlights, so that the wide world dwindled to a warm quiet room. Neil McCodrum was the last to drag his boat up the shingle and hoist the creel of fish upon his back. He stood a while watching the seabirds fly low towards the headland, their wings dark against the evening sky, then turned to trudge up the shingle to the croft on the machair.

It was as he turned, he saw something move in the shadows of the rocks. A glimmer of white and then - he heard it between birds’ cries - high laughter like silver. He set down the creel, and with careful steps he neared the rocks, hardly daring to breathe, and hid behind the largest one. And then he saw them - seven girls with long dark flowing hair, naked and white as the swans on the lake, dancing in a ring where the shoreline met the sea.

And now his eye caught something else - a shapeless pile of speckled brown skins lying heaped like seaweed on a boulder nearby. Now Neil knew that they were selkie, who are seals in the sea, but when they come to land, take off their skins and appear as human women.

Humped low so he would not be seen, Neil McCodrum crept towards the pile of skins, and slowly slid the top one down. But scarcely had he rolled it up and put it under his coat, than one of the selkie gave a sharp cry. The dance stopped, the circle broke, and the girls ran to the boulder, slipped into their skins and slithered into the rising tide, shiny brown seals that glided away into the dark night sea.

All but one.

She stood before him as white as a pearl, as still as frost in starlight. She stared at him with great dark eyes, then slowly she held out her hand, and said in a voice that trembled with silver:

“Ochone, ochone! Please give me back my skin.”

He took a step towards her and she stared at him with large brown eyes that held the depths of the sea. “Come with me,” he said, “I will give you new clothes to wear.”

The wedding of Neil McCodrum and the selkie woman was set for the time of the waxing moon and the flowing tide. All the folk of the clachan came, six whole sheep were roasted and the whiskey ran like water. Toasts overflowed from every cup for the new bride and groom, who sat at the head of the table: McCodrum, beaming and awkward, unused to pleasure, tapped his spoon to the music of fiddle and pipe, but the woman sat quietly beside him at the bride-seat, and seemed to be listening to another music that had in it the sound of the sea.

After a while she bore him two children, a boy and a girl, who had the sandy hair of their father, but the great dark eyes of their mother, and there were little webs between their fingers and toes. Each day, when Neil was out in his boat, she and her children would wander along the machair to gather wild parsnips and berries, or fill their creels with carrageen from the rocks at low tide. She seemed settled enough in the croft on the shore, and in May-time when the air was scented with thyme and roseroot and the children ran towards her, their arms full of wild yellow irises, she was almost happy. But when the west wind brought rain, and strong squalls of wind that whistled through the cracks in the croft walls, she grew restless and moved about the house as if swaying to unseen tides, and when she sat at the spinning-wheel, she would hum a strange song as the fine thread streamed through her fingers. McCodrum hated these times and would sit in the dark peat-corner glowering at her over his pipe, but unable to say a word.

Thirteen summers had passed since the selkie woman came to live with McCodrum, and her children were almost grown. As she knelt on the warm earth one afternoon, digging up silverweed roots to roast for supper, the voice of her daughter Morag rang clear and excited through the salt-pure air and soon the girl was beside her holding something in her hands.

“O mother! Is this not the strangest thing I have found in the old barley-kist, softer than the mist to my touch?”

Her mother rose slowly to her feet, and in silence ran her hand along the speckled brown skin. It was smooth like silk. She held it to her breast with one hand, and put her other arm around her daughter, and walked back with her to the croft in silence, heedless of the girl’s puzzled stares. Once inside, she called her son Donald to her, and spoke gently to her children:

“I will soon be leaving you, mo chridhe, and you will not see me again in the shape I am in now. I go not because I do not love you, but because I must become myself again.”

That night, as the moon sailed white as a pearl over the western sea, the selkie woman rose, leaving the warm bed and slumbering husband. She walked alone to the silent shore and took off her clothes, one by one, and let them fall to the sand. Then she stepped lightly over the rocks and unrolled the speckled brown parcel she carried with her, and held it up before her. For one moment maybe she hesitated, her head turning back to the dark, sleeping croft on the machair; the next, she wrapped the shining skin about her and dropped into the singing water of the sea.

For a while a sleek brown head could be seen in the dip and crest of the moon-dappled waves, pointing ever towards the far horizon, and then, swiftly leaping and diving towards her, came six other seals. They formed a circle around her and then all were lost to view in the soft indigo of the night.

In the croft on the machair, Neil McCodrum stirred, and felt for his wife, but his hand encountered a cold and empty hollow. He knew better than to look for her and he also knew she would never come to him again. But when the moon was young and the tide waxing, his children would not sleep at night, but ran down to the sands on silent webbed feet. There, by the rocks on the shoreline, they waited until she came - a speckled brown seal with great dark eyes. Laughing and calling her name, they splashed into the foaming water and swam with her until the break of day.