The night which is Solstice Eve winters deepest with the misery and solitude of this time of year. At least, that’s how I sense the hour. Just how personal that vibe is -- the resonant eddies of bum fortune -- and how collective? To me the bells of Christmas ring hollow, far across a frozen land, announcing an old liturgy which has mostly lost all warmth -- and yet that hard sound is reverent. “In my end is my beginning,” said Eliot in “Four Quartets,” a poem more wintry in its way than “The Wasteland.”

Is this the sum of my self-evictions from a tradition, throwing out the baby Jesus to immerse myself in that bathwater? The chill wasn’t there in my childhood, or it was greatly bowered by my parents’ love, difficult though that was for each other. They damn near killed themselves to do everything they could for us. Only outside it was cold and infernally dark; those winds whipped the eaves of that big house in Evanston like wolves, but I slept deep down into “The Nutcracker Suite,” dancing with sugarcoated and tutu’d elvenettes sporting nipples of blue ice.

How did I get evicted? Was there a choice, or did I just grow up into my world? Came and left the faith in Christian Christ; out I went into the solace of a mythically poisoned night; came the years of hard drinking and ravening about for some font of always-insufficient warmth. The music of Christmas grew hollow and deep, as much about absence and solitude as comforts lost.

A pregnant solitude: isn’t that the aegis of Christmas? That hope is greatest exactly where it is most lost? That sentiment I named in the poem “Longing”:

.. I recall a young man

walking home drunk on a

frozen night long ago,

his beloved nowhere

to be found in the chalice

he had named. Winds hurled

steel axes through the

Western sky, failing to clear

the cruel foliage of fate.

In his defeat he was greater

than any angel beckoned

by that night: his heart so

hollowed by longing

as to chance in pure cathedral,

her absence the clabber of a bell

shattering the frozen air,

trebling the moon

without troubling a sound.

That’s me in 2002 writing about me in 1977, learning to hallow the hollowness of those nights with the words that ripened somewhere out on those lost walks in the dead of winter.

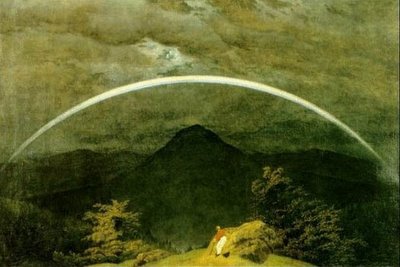

Years later -- in 1986, I think, very close to the end of my first drinking career -- I dreamed of walking a winter waste somewhere in the Harst Mountains of Germany or some such deep-frozen locale, on a moony night which shone dully of vast acreage of snow, all dead and still beneath that burning moon and the angel fire of far stars. There was a farmhouse that I came upon, and, looking through a window, I saw a couple by the fire, the woman pregnant, sitting in a chair, the husband bearded, tending the scene, the room vastly aglow and impossible for one such as me to enter. So I trudged back to the night and winter and ghastly moonlight: back to the wolves.

I woke back to my awfulness, but certainly something was entering labor, for soon came the events which caused me to quit drinking and start living, finding in sobriety a way of building and sustaining a house of warmth -- the place I live in today. Much reading and writing has made cathedral the small nook of excavation and celebration I attend every early morning here.

Still the music echoes in such a sad and lonely way -- especially ny unaccompanied vocal music of the season, Gregorian Chant, Palestrina, Vaughan Williams -- but bittersweet is a strange nuance, comforting even as it freezes. Again, a personal or mythic resonance? When I’ve asked around, no one quite gets the same feeling.

Maybe its part of that old unrequieted longing, towering as equally in the stumbling drunk youth trying to walk home as the bumbling senex going over and over the routes. Old and new year kings at their trysting ground, Green Knight and Gawain, Oran and Columba, winter solstice and Christmas: Faces of dominions staring at each other in such an ancient way that it has an archetypal sound to it, saddling our responses with primary riders and first causes.

Commenting on the Finnish tale “The Boy Born of An Egg,” where a sorely neglected and abused orphan emerges a triumphant god, Karl Kerenyi notes, “this material is undoubtedly the primal stuff of mythology, and not of biography; a stuff from which the life of gods, and not the life of men, is formed. What, from the purely human point of view, is an unusually tragic situation -- the orphan’s exposure and persecution -- appears in mythology in quite another light. It simply shows up in the lonelienss and solitude of elemental beings -- a loneliness peculiar to the primordial element.

“If anything, the fate of the orphaned Kullervo, delivered up to every force of destruction exposed to all the elements, must be

the orphan’s fate in the fullest sense of the word, exposure and prosecution. But at the same time this fate is the triumph of the elemental nature of the wonder-child. The

human fate of the orphan does not truly express the fate of such miraculous beings, is only secondary. Yet it is just their symbolical orphanhood that gives them their significance: it expresses the

primal solitude which alone is appropriate to such beings in such a situation, namely in mythology.” (“The Primordial Child in Primordial Times”)

Is the loneliness of Christmas that of every child abandoned by God to fare forth on this earth, as every uteral fish must leave its sea to blunder past all shores? What homesickness, what hopelessness, faces of divine mother and father always behind the masks of personal parents, the elusive mystery somewhere deeper in the history. I still think the divine bastard is cultural too, God absented from our altars for too many centuries now, so that absence is god, calling us to matins and vespers ...

Eliot looked hard into the face of that cruel adulthood, and, looking to survive his Wasteland, chose to return to the Christian fold, that womb which seeks to remit time and the pain of our adulthood: He quailed, though so perfectly. This from “The Dry Salvages” of Four Quartets, written during the darkest years of World War II:

II

Where is there an end of it, the soundless wailing,

The silent withering of autumn flowers

Dropping their petals and remaining motionless;

Where is there and end to the drifting wreckage,

The prayer of the bone on the beach, the unprayable

Prayer at the calamitous annunciation?

There is no end, but addition: the trailing

Consequence of further days and hours,

While emotion takes to itself the emotionless

Years of living among the breakage

Of what was believed in as the most reliable-

And therefore the fittest for renunciation.

There is the final addition, the failing

Pride or resentment at failing powers,

The unattached devotion which might pass for devotionless,

In a drifting boat with a slow leakage,

The silent listening to the undeniable

Clamour of the bell of the last annunciation.

Where is the end of them, the fishermen sailing

Into the wind's tail, where the fog cowers?

We cannot think of a time that is oceanless

Or of an ocean not littered with wastage

Or of a future that is not liable

Like the past, to have no destination.

We have to think of them as forever bailing,

Setting and hauling, while the North East lowers

Over shallow banks unchanging and erosionless

Or drawing their money, drying sails at dockage;

Not as making a trip that will be unpayable

For a haul that will not bear examination.

There is no end of it, the voiceless wailing,

No end to the withering of withered flowers,

To the movement of pain that is painless and motionless,

To the drift of the sea and the drifting wreckage,

The bone's prayer to Death its God. Only the hardly, barely prayable

Prayer of the one Annunciation.

It seems, as one becomes older,

That the past has another pattern, and ceases to be a mere sequence-

Or even development: the latter a partial fallacy

Encouraged by superficial notions of evolution,

Which becomes, in the popular mind, a means of disowning the past.

The moments of happiness-not the sense of well-being,

Fruition, fulfilment, security or affection,

Or even a very good dinner, but the sudden illumination-

We had the experience but missed the meaning,

And approach to the meaning restores the experience

In a different form, beyond any meaning

We can assign to happiness. I have said before

That the past experience revived in the meaning

Is not the experience of one life only

But of many generations-not forgetting

Something that is probably quite ineffable:

The backward look behind the assurance

Of recorded history, the backward half-look

Over the shoulder, towards the primitive terror.

Now, we come to discover that the moments of agony

(Whether, or not, due to misunderstanding,

Having hoped for the wrong things or dreaded the wrong things,

Is not in question) are likewise permanent

With such permanence as time has. We appreciate this better

In the agony of others, nearly experienced,

Involving ourselves, than in our own.

For our own past is covered by the currents of action,

But the torment of others remains an experience

Unqualified, unworn by subsequent attrition.

People change, and smile: but the agony abides.

Time the destroyer is time the preserver,

Like the river with its cargo of dead negroes, cows and chicken coops,

The bitter apple, and the bite in the apple.

And the ragged rock in the restless waters,

Waves wash over it, fogs conceal it;

On a halcyon day it is merely a monument,

In navigable weather it is always a seamark

To lay a course by: but in the sombre season

Or the sudden fury, is what it always was.

***

So my gall and pall over what I hear as sad bells in a frozen waste have a backwards and forwards tide to them, surging from primacy to crashing futurity and thus ebbing back. I love those voices, the lonely chant of the matin hour, deep inside the petrified ribs of the world, or its God: a difficult hour but and ecstasy worth adding my assent to, my voice.

***

OK, foax, now to harrow the hour with these solstitial readings:

CHRISTMAS TREE

IN THE GARDENDec. 21, 2005

All night we’ve kept the lights

burning on the Christmas tree

in the garden, and at 4 a.m.

it’s pure candlepower, a fir

of stars. The fire which sustains

every dream of the year

both ending and soon to wake

is bowered on that tree,

at least for this night.

There is nothing greater

in the world than its

uncomplicated light,

nothing under it which

could be a greater gift

than what such soft

brilliance bowers and

affords on a night like this,

at this hour of our world.

Such light hinges all

beginnings and their

ends, auguring what

plants will flourish in

the garden come the

sunny months, what new

augment of the heart

will unfold its wings

and soar or dive

in perpetually summer

skies. But for now

this grace, this quiet

fortitude of small white

lights on a fir set in

the middle of the garden

with a bright red bow

tied to its upper boughs

and a single star atop its

steeple, beaming welcome

deep into the year, pointing

the way to this small

rustic manger in which

I write of all that counts

for nothing and thus

means everything with

its tiny freight now breathing

slow and sweet in the

countenance of pre-dawn

sleep and the heavens

beaming, praising, getting

to work.

***

The confection of that moment arises from a hard blue loam; witness, if you will,

***

THE BAD YEARSDec. 17, 2003

My bad years were a

sleep I could not wake

from. She held

me from below

pressing her blue

thirst to my lips,

a honey milk

with a threat

of gall through which

She poured her angels

and devils in.

Poured them all.

Yesterday I

remembered a

Christmas at my

father’s place in

1977 when I

thought I would

abandon my useless

and unworthy

and broken life out

West and come

to live at last

with him, partaking

there of a New Age

dream of devas

rousing winter

gardens and raising

ley-lords from

their witchy rooks

in the stone

foundations never

far below. We drank

his B&B Scotch

(cheap and plentiful)

next to the fire

that late December

hashing out David

Spangler’s “Principles

of Manifestation,”

those quantum

mechanae of the

soul which, as

we boiled them down,

seemed only to

say, To Be Is Being’s

Be-All: So Be.

Dry ends indeed

to such high yeasty

talk, but we kept

on talking and drinking.

Up the road in a

double-wide trailer

lived drunk Karol and

his even drunker

son Randy, both

catastrophes of

the same booze

we thought we caged

with all that high

talk. The father was

a Polish refugee

from World War II’s

boneyard of atrocity.

He hated the Germans

but despised the

Russians worse, who

one hoary winter’s day

rounded up he and

his fellow villagers

into a cattle car

and chugged into

deep woods, where

they disembarked

the men and lined

them up along a ridge,

and solved all seed

of feared insurgency

by emptying their

ratatats into Karol

and his tribe.

He fell in sync

with the rest, miraculously

free of shot, and

faked his death

sprawled in that

pile of cooling meat.

After dusk he crawled

up and out, a revenant

who had only in the

coldest sense of

things survived.

Hid out til war’s

end then worked

his way this way,

setting up at last

in that trailer

up the road to work

his days like a bull

and drink his nights

like the worst whale.

My father loved

Karol’s workhorse

ways, hiring him

now and then for

some or other

big job on his land,

which back then

was a total mess,

years from becoming

something fine,

a Yankee Piccu

shored between

high rhetorics and

a damn fine, soul-

rich ground. Back

then it was only

guesswork and

long long hours of

work, days and years

of it. Those early

times required a titan’s

back and hands,

and Karol for some

while was the

best of that. By

day, at least; they’d

drunk some Scotch

together but the

beast who emerged

in the third pour

was no man my

father cared to house,

and told Karol he’d

had to drink elsewhere.

By the time I

had gotten there,

Karol was mostly

a story, his sweat

and swath something

reserved for spring

days down the road.

A day or so

before Christmas

my brother roared

into town, a party

boy like me in full

bored merriment,

on fire just as I

but lacking my

dad’s approval,

mostly because the

words were not in

his mouth but

further down in

his hands. It would

be years before he’d

find use for them;

back then they were

most adept at

chugging and charging

at the night. He linked

up somehow his

Randy and Randy’s

sister and drove

off with them to

party wild and long,

fucking the sister

in the back seat while

Randy cheered,

the station wagon’s

interior a furnace

for a winter’s night.

My brother told me

off all this the next

day as he came

to with coffee and

some snuck-in shots

of Scotch, his eyes

like black holes,

a dark sad woman

staying back

far far far below.

A week later Randy

invited us up to

his father’s trailer

to celebrate the New

Year’s. Karol was

already roaring drunk,

one meaty fist

choking the life

out of a half-gallon

of vodka, the other

keeping time to

a polka band on

the stereo, his eyes

red with all he still

could see too well.

The trailer was decked

with streamers and

glitter, too sickly-bright,

too campy, composing

a merriment almost

infernal in its gleam.

Ilsa the mother

back then stayed far

from sight, clucking her

tongue at all the

errancy her men

brought to this small

house perched on doom.

Randy came falling

through the door

with a case of

champagne -- tumbled

through the threshold

then collapsed, shattering

half the bottles

on the floor in a

wavelike, bright

careen of sound.

Randy lay there

swearing but the

father just roared

with glee; that’s

when I got the

hell on outta there,

backing out shouting

Happy New Year’s!

and wheeling into

a cold cold frozen

Pennsylvania night,

slipping helter

skelter on icy

asphalt, sure that

every bat in hell

was wheeling overhead.

Back in my father’s

house all was settled

and noble and

warm -- my father

smoking his pipe

reading in a chair,

Pachelbel’s “Canon

in D” on his stereo,

a big cross over

the mantel blessing

for sure this

enterprise. It was

exactly where I

wished to be:

though I knew

somehow it was

exactly the place

it was somehow

most dangerous

to remain. One

of those nights

the dreams began --

a horrible parade of

desperate scenes,

as if some warning

was shrieking from

a sidhe that bound

my sleep. In one

dream I was trapped

inside some

motherish castle,

a feminine keep,

while some fatherish

light assaulted

from without, promising

to annihilate every

living presence with

the audacity to

keep the door tight.

In another dream

I voyaged in a balloon

into mystic China

with a strange stone

man who bore

inscriptions on his

neck in no language

I yet could understand.

As we began the most

dangerous passage,

the stone man

scrambled out of

the basked and

fell like stone below,

leaving me alone

just when the

clouds were thickest

and the strangeness

most intent. I’d

belt awake from

those dreams,

my heart hammering

hard, certain only

that my promise

to stay on at

my father’s place

was not at all

concurred with

from below; that

not matter how much

I wished to stay,

I had only one

way to go and

survive -- away, back

west to my own meager

awful limited life.

My dad was hurt

and perplexed when

I eventually announced

that as much as I

loved all there, it

was not mine nor

what I must build.

I said those words

to my father in

January 1978, and

I have never since

been able to stay

there for very long.

At the end of

that month I flew

back to Spokane

to that cold house

I rented, entering

the spring semester

of my junior year

in college, which

turned out to be

the last full-time

school effort I

could manage. It

was the semester

of good poetry

at last and a woman

who emerged from

the blue dark

corners of some

party who eventually

took me by the

hand and drowned me

in my own bed.

That I guess was

the fate sealed on

the stone man’s lips

when he followed

a deeper instinct

and left the air

with its New Agey

wisps and aetherizing.

He dove into what I

followed and here

keep sinking to -- Mystic

rivers and oceans

which will never

quite do, a harpuscry

or hagiography or

mantic musings of

some blue I could never

find on my father’s

higher ground.

Sometime soon after

I returned out West

my father called

to tell me that

Karol was dead.

One night he’d

gotten roaring drunk

as usual and then

drove home on

quite icy roads.

He didn’t make

it round that big

curve behind my

father’s house

and sailed off the road

and down the

ravine, catching

a broad tree right

between the eyes.

Finis. That story

didn’t really surprise

me -- you saw bad

ends hanging all over

that Christmas tree

in his doublewide

up the road -- And

we both agreed that

the roar of rage

at old wounds could

only be quieted in

the grave. Hearing

that story way back

then didn’t change

my ways at all, for I

was young and much

smarter than all

that, with all my

history ahead, and

my words of such

a finer distillation

as to keep me

wide of those

widest curves.

Ha ha. That I survived

and have lived to

tell the story is

somehow Her

prerogative, as if I

am now not the

mantic but one

gifted by God or Goddess

to read his stony

lips, a pen dipped

in deep old ink

now asked to write

it out. Many years

later in my first

round of sobriety,

I heard from the son

Randy who had

seemed sealed into

his father’s aphotic

shoes. But instead

he had gotten sober

in AA and found a

way into the live

above and beyond

that grave, working

as a nurse and going

still further to love.

The man I saw in ‘92

was like a sailor

who’d been lost

for years but somehow

returned, much aged,

his face almost

completely changed, like

a stone worn

smooth washed

long in blue. We

didn’t really have

much to say to

each other, but

just seeing us

both on the other shore

from so many bad

years was satisfaction

enough, like twins

separated at some

brutal birth will

recognize the

other instantly though

there’s nothing else

to say. We lived on

beyond those black

and revenant years,

to begin our lives

at last. We said

farewell, and that

was that. Years later,

in an AA meeting

yesterday, the story

came bubbling up

to view in my mind,

much covered with

weeds and barnacles

and faded to a greyish-

brown: Yet as

the others told Christmas

memories of their

drinking worst, this

one for me began to

gleam and unfold its

strange wings at last,

an oracle, if you

will, from the grave

of bad years lost.

The voice reminded

me to be thankful

with the rest of my life

to be sitting here

and not back there

where the moon

over Christmas

wore the devil’s

ice pegnior, and my

thirst for darkness

was so endless:

And to be thankful

too exactly for

that way in which

She grabbed and held

me long below,

whispering those

strange blue words

which makes every

poem now go

and glow and make

all ripened curves

on dark road show.

***

Survival of that winter required a pose, an angle toward the wind, which I interpreted as

***

THE SOLSTICE DUDE1991

Out in the land of purple twilight,

There in death valley of solsticeville,

I met the Solstice Dude by a frozen river.

He had a ‘56 Telecaster over one shoulder

and wore black jeans, black leather jacket,

black night boots with a moon buckle.

The night was cold, cold as shit

leached from a witch’s tit:

All my absence hugged me like a grave.

The Solstice Dude came at me with ice licks

that spun like shirrikins.

His eyes were tiny floodlights of blood,

his hair cascading falls, his smile, celestial.

What could I do? How could I resist?

A boy shivering in a jean jacket,

afraid of women, fleeing from his father.

I tried to dodge his chops

but one caught me in the shoulder.

I fell beneath a totem pole. . .

blizzard-clouds obscured the eagle at the top,

my angel in the snow fell far.

The poison crept slow, insidious as that

winter of ‘79, as I sat at the heat-grate,

sucking my beer like a tit of no avail.

I just got colder and colder.

Who was dying?

Thighs of night to no avail.

At practice my fingers had no fire,

I blew my solos, lost the end of songs.

In the mirror I saw a mad boy

possessed by the Solstice Dude,

gripped by an ancient in contemporary threads.

Controlled by the spirit, addicted to

spirits, soul of no avail,

winter tit, ice-whale belly -

No snow fell. The wind in the pines,

eternal, bending and breaking their backs.

Deep in the forest woumb, the Solstice Dude

stands on a rack of Marshall amps.

Blood’s all over the ancient Tele neck.

Antlers rise above his head.

The world tree reaches far below.

A snake nooses his neck: he jumps:

A madman, an addict, alcoholic,

wanderer over all forgotten streets,

patron of the dead a.m.s,

poison luminary of the mothernight deep,

forever zoned in twilight,

a skip at the record’s end:

the Solstice Dude lives within

those who fail to murder him.

Finally, I walked onstage,

held my guitar high:

my fingers bled and I sweated rivers.

The band died there, on a night,

I impaled the Solstice Dude with

an unglamorous Music Man Sabre

as we crashed to the end of

the Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen”.

The antlers were heavy, my mouth twisted,

and the Solstice Dude fell

into a jade pool and drowned.

***

Rock dreams indeed. Far into that long winter’s night, around 1977, I read Thomas Pynchon’s

Gravity’s Rainbow (1974), that great postmodern gospel which served then as my Book of the Dead during the darkest hours of personal solstice. The book is set in England during the worst years of WWII, as the German V2 rockets came screaming across the sea. In the following passage it is winter, a time like this, close to Christmas. It is utterly aborbed with the sense of loss which Eliot could not sustain, raising it to an nth power, cathedral in its own right, housing a God of night, perhaps, or opening the door to the darkest lucency below: the sacred resonance of absence.

***

Advent blows from the sea, which at sunset tonight shone green and smooth as iron-rich glass: blows daily upon us, all the sky above pregnant with saints and slender heralds’ trumpets. Another year of wedding dresses abandoned in the heart of winter, never called for, hanging in quiet satin ranks now, their white-crumpled veils begun to yellow, rippling slightly only at your passing, spectator . . . visitor to the city at all the dead ends. . . . Glimpsing in the gowns your own reflection once or twice, halfway from shadow, only blurred flesh-colors across the peau de soie, urging you in to where you can smell the mildew’s first horrible touch, which was really the idea—covering all trace of her own smell, middleclass bride-to-be perspiring, genteel soap and powder. But virgin in, her heart, in her hopes. None of your bright-Swiss or crystalline season here, but darkly billowed in the day with cloud and the snow falling like gowns in the country, gowns of the winter, gentle at night, a nearly windless breathing around you. in the stations of the city the prisoners are back from Indo-China, wandering their poor visible bones, light as dreamers or men on the moon, among chrome-sprung prams of black hide resonant as drumheads, blonde wood high-chairs pink and blue with scraped and mush-spattered floral decals, folding-cots and bears with red felt tongues, baby-blankets making bright pastel clouds in the coal and steam smells, the metal spaces, among the queued, the drifting, the warily asleep, come by their hundreds in for the holidays, despite the warnings, the gravity of Mr. Morrison, the tube under the river a German rocket may pierce now, even now as the words are set down, the absences that may be waiting them, the city addresses that surely can no longer exist. The eyes from Burma, from Tonkin, watch these women at their hundred perseverances-stare out of blued orbits, through headaches no Alasils can ease. Italian P/Ws curse underneatb the mail sacks that are puffing, echo-clanking in now each hour, in seasonal swell, clogging the snowy trainloads like mushrooms, as if the trains have been all night underground, passing through the country of the dead. If these Eyeties sing now and then you can bet it’s not “Giovinezza” but something probably from Rigoletto or La Boheme—indeed the Post Office is considering issuing a list of Nonacceptable Songs, with ukulele chords as an aid to ready identification. Their cheer and songful ness, this lot, is genuine up to a point-but as the days pile up, as this orgy of Christmas greeting grows daily beyond healthy limits, with no containment in sight before Boxing Day, they settle, themselves, for being more professionally Italian, rolling the odd eye at the lady evacuees, finding techniques of balancing the sack with one hand whilst the other goes playing “dead”—

cioe, conditionally alive—where the crowds thicken most feminine, directionless . . . well, most promising. Life has to go on. Both kinds of prisoner recognize that, but there’s no

mano morto for the Englishmen back from CBI, no leap from dead to living at mere permission from a likely haunch or thigh-no play, for God’s sake, about life-and-death! They want no more adventures: only the old dutch fussing over the old stove or warming the old bed, cricketers in the wintertime, they want the semi-detached Sunday dead-leaf somnolence of a dried garden. If the brave new world should also come about, a kind of windfall, why there’ll be time to adjust certainly to that. . . .But they want the nearly postwar luxury this week of buying an electric train set for the kid, trying that way each to light his own set of sleek little faces here, calibrating his strangeness, well-known photographs all, brought to life now, oohs and aahs but not yet, not here in the station, any of the moves most necessary: the War has shunted them, earthed them, those heedless destroying signalings of love. The children have unfolded last year’s toys and found reincarnated Spam tins, they’re hep this may be the other and, who knows, unavoidable side to the Christ mas game. In the months between-country springs and summers—they played with real Spam tins-tanks, tank-destroyers, pillboxes, dreadnoughts deploying meat-pink, yellow- and blue about the dusty floors of lumber-rooms or butteries, under the cots or couches of their exile. Now it’s time again. The plaster baby, the oxen frosted with gold leaf and the human-eyed sheep are turning real again, paint quickens to flesh. To believe is not a price they pay-it happens all by itself. He is the New Baby. On the magic night before, the animals will talk, and the sky will be milk. The grandparents, who’ve waited each week for the Radio Doctor asking, What Are Piles? What Is Emphysema? What Is A Heart Attack? will wait, up beyond insomnia, watching again for the yearly impossible not to occur, but with some mean residue-this is the hillside, the sky can show us a light-like a thrill, a good time you wanted too much, not a complete loss but still too far short of a miracle . . . keeping their sweatered and shawled vigils, theatrically bitter, but with the residue inside going through a new winter fermentation every year, each time a bit less, but always good for a revival at this season. . . . All but naked now, the shiny suits and gowns of their pubcrawling primes long torn to strips for lagging the hot-water pipes and heaters of landlords, strangers, for holding the houses’ identities against the w inter. The War needs coal. They have taken the next-to-last steps, at tended the Radio Doctor’s certifications of what they knew in their bodies, and at Christmas they are naked as geese under this woolen, murky, cheap old-people’s swaddling. Their electric clocks run fast, even Big Ben will be fast now until the new spring’s run in, all fast, and no one else seems to understand or to care. The War needs electricity. It’s alively game, Electric Monopoly, among the power companies, the Central Electricity Board, and other War agencies, to keep Grid Time synchronized with Greenwich Mean Time. In the night, the deepest concrete wells of night, dynamos whose locations are classified spin faster, and so, responding, the clock-hands next to all the old, sleepless eyes, gathering in their minutes whining, pitching higher toward the vertigo of a siren. It is the Night’s Mad Carnival. There is merriment under the shadows of the minute-hands. Hysteria in the pale faces between the numerals. The power companies speak of loads, war-drains so vast the clocks will slow again unless this nighttime march is stolen, but the loads expected daily do not occur, and the Grid runs inching ever faster, and the old faces turn to the clock faces, thinking

plot, and the numbers go whirling toward the Nativity, a violence, a nova of heart that will turn us all, change us forever to the very forgotten roots of who we are. But over the sea the fog tonight still is quietly scalloped pearl. Up in the city the arc-lamps crackle, furious, in smothered blaze up the centerlines of the streets, too ice-colored for candles, too chill-dropleted for holocaust . . . the tall red busses sway, all the headlamps by regulation newly unmasked now parry, cross, traverse and blind, torn great fistfuls of wetness blow by, desolate as the beaches beneath the nacre fog, whose barbed wire that never knew the inward sting of current, that only lay passive, oxidizing in the night, now weaves like underwater grass, looped, bitter cold, sharp as the scorpion, all the printless sand miles past cruisers abandoned in the last summers of peacetime that once holidayed the old world away, wine and olive-grove and pipesmoke evenings away the other side of the War, stripped now to rust axles and brackets and smelling inside of the same brine as this beach you cannot really walk, because of the War. Up across the downs, past the spotlights where the migrant birds in autumn choked the beams night after night, fatally held till they dropped exhausted out of the sky, a shower, of dead birds, the compline worshipers sit in the unheated church, shivering, voiceless as the choir asks: where are the joys? Where else but there where the Angels sing new songs and the bells ring out in the court of the King. “Eia” — strange thousand-year sigh-”eia, warn wir da!”, “were we but there”. . . . The tired men and their black bellwether reaching as far as they can, as far from their sheeps’ clothing as the year will let them stray. Come then. Leave your war awhile, paper or iron war, petrol or flesh, come in with your love, your fear of losing, your exhaustion with it. All day it’s been at you, coercing, jiving, claiming your belief in so much that isn’t true. Is that who you are, that vaguely criminal face on your ID card, its soul snatched by the government camera as the guillotine shutter fell-or maybe just left behind with your heart, at the Stage Door Canteen, where they’re counting the night’s take, the NAAFI girls, the girls named Eileen, carefully sorting into refrigerated compartments the rubbery maroon organs with their yellow garnishes of fat-oh Linda come here feel this one, put your finger down in the ventricle here, isn’t it swoony, it’s still going. . . . Everybody you don’t suspect is in on this, everybody but you: the chaplain, the doctor, your mother hoping to hang that Gold Star, the vapid soprano last night on the Home Service programme, let’s not forget Mr. Noel Coward so stylish and cute about death and the afterlife, packing them into the Duchess for the fourth year running, the lads in Hollywood telling us how grand it all is over here, how much fun, Walt Disney causing Dumbo the elephant to clutch to that feather like how many carcasses under the snow tonight among the white-painted tanks, how many hands each frozen around a Miraculous Medal, lucky piece of worn bone, half-dollar with the grinning sun peering up under Liberty’s wispy gown, clutching, dumb, when the 88 fell-what do you think, it’s a children’s story? There aren’t any. The children are away dreaming, but the Empire has no place for dreams and it’s Adults Only in here tonight, here in this refuge with the lamps burning deep, in pre-Cambrian exhalation, savory as food cooking, heavy as soot. And 6o miles up the rockets hanging the measureless instant over the black North Sea before the fall, ever faster, to orange heat, Christmas star, in helpless plunge to Earth. Lower in the sky the flying bombs are out too, roaring like the Adversary, seeking whom they may devour. It’s a long walk home tonight. Listen to this mock-angel singing, let your communion be at least in listening, even if they are not spokesmen for your exact hopes, your exact, darkest terror, listen. There must have been evensong here long before the news of Christ. Surely for as long as there have been nights bad as this one-something to raise the possibility of another night that could actually, with love and cockcrows, light the path home, banish the Adversary, destroy the boundaries between our lands, our bodies, our stories, all false, about who we are: for the one night, leaving only .the clear way home and the memory of the infant you saw, almost too frail, there’s too much shit in these streets, camels and other beasts stir heavily outside, each hoof a chance to wipe him out, make him only another Messiah, and sure somebody’s around already taking bets on that one, while here in this town the Jewish collaborators are selling useful gossip to Imperial Intelligence, and the local hookers are keeping the foreskinned invaders happy, charging whatever the traffic will bear, just like the innkeepers who’re naturally delighted with this registration thing, and up in the capital they’re wondering should they, maybe, give everybody a number, yeah, something to help SPQR Record-keeping ... and Herod or Hitler, fellas (the chaplains out in the Bulge are manly, haggard, hard drinkers), what kind of a world is it (“You forgot Roosevelt, padre,” come the voices from the back, the good father can never see them, they harass him, these tempters, even into his dreams: “Wendell Willkiel” “How about Churchill?” “‘Arry Pollitt!”) for a baby to come in tippin’ those Toledos at 7 pounds 8 ounces thinkin’ he’s gonna redeem it, why, he oughta have his head examined. . . .But on the way home tonight, you wish you’d picked him up, held him a bit. just held him, very close to your heart, his cheek by the hollow of your shoulder, full of sleep. As if it were you who could, some how, save him caring who you’re supposed to be registered as. For the moment anyway, no longer who the Caesars say you are.

0 Jesu parvule,

Nach dir ist mir so weh . . .So this pickup group, these exiles and horny kids, sullen civilians called up in their middle age, men fattening despite their hunger, flatulent because of it, pre-ulcerous, hoarse, runny-nosed, red-eyed sorethroated, piss-swollen men suffering from acute lower backs and all-day hangovers, wishing death on officers they truly hate, men you have seen on foot and smileless in the cities but forgot, men who, don’t remember YOU either, knowing they ought to be grabbing a little sleep, not out here performing for strangers, give you this evensong, climaxing now with its rising fragment of some ancient scale, voices overlapping threeand fourfold, up, echoing, filling the entire hollow of the church-no counterfeit baby, no announcement of the Kingdom, not even a try at warming or lighting this terrible night, only, damn us, our scruffy obligatory little cry, our maximum reach outward —

praise be to God! — for you to take back to your war-address, your war-identity, across the snow’s footprints and tire tracks finally to the past you must create for yourself, alone in the dark. Whether you want it or not, whatever seas you have crossed, the way home ...

***

So now I had a language for my dark, a way of reading and saying it, and those words led me slowly deeper and out the labyrinth I have come to celebrate, especially at this time of year.

Shamanic Letters is finished, I packaged 25 of them and FedX’d them yesterday to my father for his solstice, father of mine, tuletary father of the deep father shaman who rides and whips these words.

Anyway, to resume the narrative:

***

SOLSTICE CHANTfrom “A Breviary of Guitars,” 2000

Winter 1984:

I fly up to

my father’s

Columcille

in the Poconos

of Pennsylvania

for the Christmas

holiday, arriving

ebbed with

flu, burnt out,

hungover, weary

to death, my

heart raged

down to char:

And crossing

my father’s

threshold is

like stepping

over a boundary

into other

time: By then

the place had

grown to the

Celtic digs which

had inspired

the name: Inside

it’s all stone

& wood and

candles, glowing

and warm where

outside it’s

bitter cold,

naked, chilled with

a foggy sleet:

& of course as

I always do I

fall in love

with the place

& its making,

the part of me

which belongs

to my father

shouting its

welcome across

the long waters

which separate

father from son:

By then the

Saint Oran

story had grown

into the timbers

of conversation

& work: A bell

tower named

for him down

in one corner

of the field

raising a few

rows of stone

a year: Some

tandem between

that building

and Oran’s

travels down

under facing

the Saint Columba

chapel in the

woods & that

saint’s white

certainty: You

walked through

one toward the

other in the

daily procession

to vespers: On

the winter

solstice after

dinner we

walked out from

the warm house

wrapped tight

in heavy clothes

into a sleeting

windy cold

night, the sky

the color of

a turgid purple

sea, icy rain

pelting our faces

slow &

incessant, the

bones of sumac

& elm & oak

creaking badly

in the hard

breeze: We

walk down from

the house round

a pond they

had dug from

the Garden of

Life the summer

before, now

black waters

like the pupil

of a huge eye

staring at us

from some

unspeakable

depth: Into the

Saint Oran

bell tower & stand

in that narrow

round chamber

watching clouds

mash and swirl

above: Light a

candle & set

it in a bitter

nook of icy

stone: Then walk

out the other

door which empties

into the eternally

descending time:

A circle of

boulders glazed

with sleet huddled

like the grim

council of

energies my

father invited

back from Iona:

A tripod of

long branches

down at the

southern end

of the field a

totem of

triune invitation:

Axis angel

of song, angry

angel of sex,

aegis angel

of work:

Into the woods

where it is

dark and

darker, creepy

with ancient

ghosts maybe

American

Indian maybe

Pict, certainly

aching: And

into the Saint

Columba chapel

built in ‘79,

an octagon

of stone walls

with a tall

pitched roof

of timber:s:

Creak open

a heavy door

of oak with

a long iron

bolster &

shuffle into

a cold so

deep it marks

the naked

boundary of

our tiny fire:

Light candles

to hoar the g

gloom & stand

round that

huge red boulder

in the center:

Rock of ages,

cleft in me:

All I have sought

elsewhere docked

somehow there,

inversed &

unreadable but

certain as stone:

Years later when

Beth & I came

up for my

brother Will’s

wedding to

Sarah we knelt

together by

that stone &

vowed our love

forever: “By

the rock of

Saint Columba

sworn” is

inscribed on the

rim of my

wedding ring

which is also

inscribed with

three Celtic

doublespirals:

I don’t know for

sure what that

oath means because

Columba’s rock

is Oran’s head,

shrouded in

mystery &

unveiled at

terrifying to

unbury: At

that solstice

I make some

sort of peace

with my wandering

affliction: As

we gather our

voices & sing

into that chilling

resonance I

join the chorus

of ages and know

somehow I

can sing those

songs & mine

as well: To that

rock I was

led by the

dearth of Columba’s

Christ & from

that rock I fled

to ramble &

rage in a

personal poisoned

dark & of

that rock I’ve

read & wrote

my own chapel

dolmen tower

& ring: On

that rock I’ve

bled my tangled

besotted horny

heart certain

only of what

I do not know:

My father has

six cremain

crypts beneath

the flagstones

round that boulder:

Grandmother

Nana fills one

of them & my

father & Fred

have dibs on

two others: I’m

welcome to join

them some day

so perhaps by

that stone one

day I’ll be

dead: Back on

the winter

solstice of

1984 standing

in the chapel

with my father

& Fred &

invoking Angels

of Rebirth and

Angels of Song

& Angels of

Being I rejoin

the dark gleaming

waters that flow

from lost aeons

into my father

and thence into

me and thus

into thee: I

still have miles

to row in

my Hamer

Phantom, much

yet to scream,

many futile

ports whose

skirts lifted

revealing that

pubic scrawl

which reads “Not

Here:” But

after that night

Oran’s music

was in the

singing of

all the ghosts

of my heart:

That stone altar

a buoy in

my depth,

compass in

whatever dark

I’ve wandered

blundered

sought &

thundered since:

***

Here the formal version of that poem:

***

MY FATHER’S CHAPEL1988

In a black-and-white photograph

my father stands before his chapel.

His face is set hard and grey

like the standing stone he rests a hand on.

The sky behind is troubled.

This is my altar to him.

My father’s chapel is hidden in the woods,

assembled from stone rows that grew from

generations of field-clearing.

Inside the chapel it is damp, dark, cool,

a descent into old regions of the world.

A quartz-veined, granite boulder

ten feet round fills the center of the chapel.

It is a heart forged in brimstone and eternal cold.

It was in my father for years before he dug it up.

My father says he is a steward of ancient spirits

he calls The Guardians. He met their chief at Iona:

Thor, the black blasted warrior of the Hebridean wind,

How my father’s heart burst with love for him. . .

One winter solstice, my father’s chapel

was bitterly cold. Frail candles flickered in

the windows, sad winds bent the bones

of trees. The death of the year.

My father and I sang together that solstice night,

our voices deepened by the resonance

of stone walls. We sang a plainchant of loss

and of infant hope. That was the dream of my father,

That is the shadow of my heart.

Tonight, on this winter solstice, I raise my

voice in song to my father’s bitter sea

that blusters deep in the conch of my ear,

a song forever trapped in the chapel of these bones.

***

And to finish with these solstice celebrations:

MANGER SCENE1994

The chill completes what

the torrid Easter bull

began: a spume of angels

breaking the virgin

into this solstice.

So few witness

the birth: two sheep,

the family mutt,

a boy on a crutch.

Three kings swoon

on straw beds

a league away,

dreaming of

starry treasure.

A palm tree spears

this morning's caul

of exhausted night.

Sunlight runnels

down the trunk

like an iron age

passing into steel.

WINTER SOLSTICE1996

Season of darkness

round a tiny garland

of light, the winter

solstice is both lovely

and lonely in its

long wake

for the day's return.

How rich the inward

comfort it affords,

its darkness rich

as the deepest cyan

in a crushed velvet

cape, urging us down

to find each other

in what we lost

so long ago, seed to soil,

son to father to son,

the tiniest hold

there upon

all losing, all

hopelessness,

tenuous and fragile

as every baby Jesus,

so weak and mewling,

thrilling the universe

one tiny heartbeat

at a time.

CHRISTMAS 1998This house has never been more our home, love,

and this poem is for the life you now unfold

each day in it, waking and working within it

going about the task in the manner you know

is the right way to go in a life.

Those company jobs never were more than

a bitter pill for you, and you have suffered

long enough in someone else's yoke of duty.

What a delight to see your eyes so lit

with eagerness and expectation as you drink

coffee in the living room, Christmas music

on the stereo, the cats gathered around you like

a shawl and cool morning air streaming in

from open windows, promising a winter yet.

I pray good luck to all your ventures,

the antique booth and refinishing trade,

the joint venture of making with your

sister, and whatever else can earn you

rite of passage forever away from

these fluorescent mills of wrong living.

Thank you for the gift of making a life

worthy for living, and for doing it with a smile.

AWAY IN A MANGER2003

New life burns here in this caul

Of coldest, year’s-end dark, an hour

No friend of love that I can name

Breaking, like a heart, this birth water;

And here, where so much already

Has been said of deep ways’ deep ends

In ripened blue, when there is nothing

More to say or sing, here we find

A tiny form at peace and sleeping

Swaddled in this humble paper shack

Far from cities, schools or spires,

A child not of any known gland

-- Oh praise the mewling vocable

Born of verses from Oran’s Well --

Bright star behind the eastern swell!

MANGER SCENE II2003

Up he rises from the dumpster

Behind the Pink Pussycat, the

Full receipt of every lost and

Forlorn ache which you deigned not

To receive. Amid the empty

Buds and butts and vomit-

Smelling rags he’s the crown prince,

Mewling (OK, groaning) as

Any babe would arising from

Such death. Well, he and I begin

Here, amid Her sordid trash.

The sour light proclaims a cracked and

Bleeding dawn -- poor afterbirth

Indeed though the psalm proclaim

New motion where old salt was lain.