Quest

The office of medicine man is not hereditary

among a considerable number of primitive

peoples ... This means that all over the world

magico-religious powers are held to be

obtainable either spontaneously (sickness,

dream, chance encounter with a source of

“power,” etc.) or deliberately (quest).

-- Mercea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic

Techniques of Ecstasy, 22

When Minos, judge of souls in Dante’s

Inferno, warns Virgil and Dante

about entering Hell, Virgil replies,

... “That is not your concern

It is his fate to enter every door.

(Inferno, V 21-2, transl. Ciardi)

***

For half of my life the quest flowed

underground, its ends unknown

to me, its means so upside-down,

the way a fool inverts a king’s gold

crown into a potty of mired sounds.

Untimely ripped from my parents’

God, I salvaged those tossed angels

as best I could, plundering every bed

from which it seemed they’d fled,

like a blue moon falling on blood-western

waves. For years the quest was what I

failed to wing, a magnitude I was too

busy barreling down to utter, much

less for more than one night sustain

But when I’d had enough of what

I never could quite find enough,

the quest appeared in opened books,

in that thirst which slaked in

reading them, each book an isle

of sufficient blue to praise new

Gods with freshened lips. In surfacing

the quest exchanged one lucre for

a next, the clout of former nights

smelt down to unfiltered umbrage

which hums low a wild humility,

the sense of who rules what below

and how little my shape counts in

the swirl of years I’m lent. The quest

topside has woven my days into

a productive, fertile loom,

jaunting across and down the inside

pages of a life which I can only

seam, my voice astride the power

chords of dragons far below

the range of human throats,

beings no moat or ramparts will

ever full challenge, much less name.

That quest I daily name as if a shore,

and, thus hallowed, free its keel

once more to harrow what it once revelled,

crossing oceans whose marge I am.

Who knows just what I’ll say

tomorrow, what strange sooth

will brogue my tongue with salt?

For years the quest rode me

underground on swells of big-night

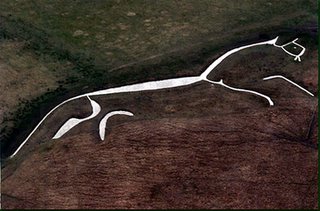

sound: For more years now I’ve

saddled Uffington with verbs

to gallop back across those

ancient mating grounds,

singing here all that I found.

And this I suspect is just two

thirds of it, the quest I mean:

just what wings will grow

from the last lines of these poems

some night I’ll drown and dream.

THE SECRETS OF THE SEA

— Lady Gregory, A Book of Saints and Wonders, 1906, Chapter 5: “Great Wonders of the Olden Time”

There are three waters of the sea now around the world, The first of them is a seven-shaped sea under the belly of the world, and against that sea hell is roaring and raising up a shout in die valley. The second is a sea green and bright round about the earth on every side; ebbing and flood it has and casting up of fruits. The third sea is a sea aflame, nine winds are let out of the heavens to call it from its sleep; three score and ten and four hundred songs its eaves sing, and it awakened; a noise of thunder comes roaring out of its wave-voice; flooding and ever flooding it is from the beginning of the world, and with all that it is never full but of a Sunday. In its sleep it is till the thunders of the winds are awakened by the coming of God’s Sunday from heaven, and by the music of the angels. Along with those there are many kinds of seas around the earth on every side; a red sea having many precious stones, bright as Flood, well coloured, golden, between the lands of Egypt and the lands of India. A sea bright, many-sanded, of the colour of snow, in the north around the islands of Sabarn. So great is the strength of its waves that they break and scatter to the height of the clouds. Then a sea waveless, black as a beetle; no ship reaching it has escaped from it again but one boat only by the lightness of its going and the strength of its sails; shoals of beasts there are lying in that sea. A sea there is in the ocean to the south of the island of Ebian. At the first of the summer it rises in flood till it ebbs at the coming of winter; half the year it is in flood it is, and half the year always ebbing. Its beasts and its monsters mourn at the time of its ebbing and they fall into sadness and sleep. They awake and welcome its flooding, and the wells and the streams of the world increase; going and coming again they are through its valleys.

THE SINGERS CHANGE,

THE MUSIC GOES ON

Linda Gregg

No one really dies in the myths.

No world is lost in the stories.

Everything is lost in the retelling,

in being wondered at. We grow up

and grow old in our land of grass

and blood moons, birth and goneness.

A place of absolutes. Of returning.

We live our myth in the recurrence,

pretending we will return another day.

Like this morning coming every morning.

The truth is we come back as a choir.

Otherwise Eurydice would be forever

in the dark. Our singing brings her

back. Our dying keeps her alive.

- from The Best American Poetry 2001,

orig. published in AGNI

UFFINGTON HORSE

2003

The locals say I am the beast

St. George slew, his white sword nailing

My heart to this hill. Well, time weaves

Tales around the hearts of men, but

I am no altar to the need

To kill the winged insides of

Every kiss. Recall how kings of

Old were taken up the hill to

Mount a pure white mare, his flesh in

Hers turned sceptre beneath the white

Applause of stars. I Rhiannon

Ride this high ground like the crest of

The ninth wave. My saddle is a

High hard throne -- mount me, if you dare.

Plunge your song in salt everywhere.

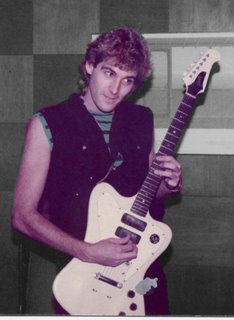

BADASS ANGELS

from “A Breviary of Guitars,” 1999

Summer 1983:

What music we

made in that

tiny hot room

on acoustic

guitars was

combustible in

a way no

prior or further

flights of song

could light:

As the sun

rose behind Kay

at the ocean

after a night

of delicious

surrender to

oceans along

the isthmus

of our bodies,

so what a

song like “Savage

Hearts” struck

flint to the

composite tinder

of our lives:

Two guys in

their mid 20s

embittered by

lost love & now

ready to howl

it loud & hard:

Rightburn in

the passion that

gripped our

guitars and

teased the flame

of songs up

from fallen

timbers, the

same old chords

from a million

same old songs

finding a new

gradient within

the music, a

beat which pounds

down and rises,

not hurrying

not stopping

but pleasuring

if you will a

center which

burns blue to

red: A killer

song, if you

will, at least

when we played

it with hearts

slapped awake

by possibility,

rising from

suburban

ordinaries on

hawk wings

up the towering

cloudbank aeries

of summer up

where the air

is thin and

cold and clear

as ice and

the archangels

glow blue and

red and the

final chorus is

a sheer swoop

down at 300

miles per hour

fixed on that

prey of lost

love: Badass

angels with

spurs & stallions

riding the

narrow edge

of anger between

loss and fury

with only the

hooves of song

to find safe

passage through

the night we

invoked:

Everything else

we added —

singer, drums,

a name, gigs —

Were all mere

accoutrement:

We both knew

the forges where

we crossed guitars:

Just not how

to tend them:

For as soon

as we crashed

down the last

chord & high

fived the future

we heard there,

the wax on our

wings kissed an

subtle urgent

fire: After practice

the nights that

unfolded were easy

because we’d

already stormed their

walls in song: Our

hearts knuckled and

muscular as we

slap some cologne

over the sweat

and rooster up the hair

and speed off

to the bars: O

we were young

and angry and

horny, our hearts

sure in the howl

of the edge: Take

some speed, smoke

a couple of bowls

of pot, pour down

a bunch of

Bud longnecks

with shots of

Old Bushmills:

That was the

correct way

to triangulate

and maze the night,

our eyes burning

behind heavy sensual

lids, as if one

glint of something

pure would burn

us to cinders:

Just a couple

of the boys

in the band

cutting into the

crowd at

Fern Park Station

like 2 blades

of moon, partying

a while before

plucking what

hung heavy and

ripe from the

pussy tree: It was

easy to score

when you

had already soared:

Four In Legion

onstage rocking

the Stones’ “Start

Me Up” and George

Thorogood’s “Bad

to the Bone” &

Ziggy walloping

his Strat like

a 19 year old

girl drunk in the

back of his van:

For what’s fire

but a bridge

between fury

and doom? Forget

finery: The

makers toil deep

in the sulphur

of their forges

grimed with sweat

and char: I

was tethered to

horses long

turned to salt

by my past: Cindy

a cipher of

other losses I

refused to read

by any light

of day: Kept

running into

her in varied

Winter Park bars

& we’d smile say

hello & then all

the walls came

tumblin’ down

between us:

The next day

shoveling purchase

orders into the

corporate forge

my heart hammering

for fear of losing

what had long

fled: And I

wonder how song

could ever suffice

for swoon: Out

in the bars

at night feeling the

ice of other

rages, the long

winter passages

in Spokane where

the song had died

in an otherwise

trackless waste,

my nights then

walking isolate

& alone through

a frozen dead

city of sleeping

citizens & dead

drunks & dead

fucks & madness

gripping down

from the north

with its bower

of absolute

zero: Draughts

of that in the

iced Stoli I

knocked back

listening to bands

overplay and strut

on other wings:

Cover songs

covering it all

up: The new songs

I was finding

(or which found

me) dipped in

that cold past

like a pen:

That’s the breath

of art: A wind

from inside

zero: It walks

the far boundary

& calls it

a homeland: Outside

summer a night

in full humid

fury, streets still

glistening with

eddies of storm

distant lightning

trilling violent

& aghast at

this order of

things & the

song making all

of that anew

& dangerous &

wildly critical

of my every

waste &

dalliance: So

when I went

out again with

Cathy to dance

again I was

hostile to her

endearments, as

if dancing were

a drowse into

love’s dungeon:

She gets drunk

real fast & I

tow her back

to my place to

nibble her clit

on the living

room floor &

Graham Parker’s

“Squeezing Out

Sparks” on the

stereo & she

falls asleep

while all the

blades are flashing

above: Next day

we hit a

matinee while storms

wrack the city

& it’s a love

scene from

a movie I recoil

from: Back at

her apartment

she pulls me from

door to bed in

one long motion

yanking down

my pants & hauling

my cock up

into her dark

furrow: I slam

away as she

grips my ass

grunting & her

big breasts mashed

against my

chest & then

bouncing every

which way

abandoning

herself to what’s

hard and harder

and thus crueler

in me: I harden

& shout or

bark this

bright angry

brass angel

which peals white

from the top

of my skull

then lets it

pour jazzy and

hot, a syrup

filling & spilling

all over her

thighs: I want

to go but for

her the sex just

opens the door

to more real

stuff, endearments

in late afternoon

& baby talk with

the cat & get

me outta here

as I fling out

at 6 p.m. enraged

& ready to

sing about it:

DRAGON’S TAIL

2003

For arrested drunks like me, there

Are only two ways to live -- The

One astride the dragon’s tail, the

Other rowing lifelong here. When

I’m riding red I’m far afield

Burning cities, hearts, and sense to

Char, backwarding on the blade which

Slices off my own ass, grabbing

All I cannot have. Off tail I’m

Pure drollery, the sea before dawn,

Nothing in my moves to catch the

Torching eye. Drunks climb on that wild

Thirst and never wake; their nightmare

Flies for life. Let them sear in soar.

My living’s calm though words here roar.

ST. BRENDAN AND THE HEATHEN GIANT

(In episode 4 of The Voyage of St. Brendan) Brendan, having had a ship built for him, finds the exceptionally large head of a dead man on the beach. Its forehead measures five feet across. When Brendan asks what kind of life he has led, the man’s head answers that he was a hundred feet tall and very strong. He was a heathen who waded through the sea to rob ships. This he did for a living. In a heavy storm which whipped up the waves to extreme heights he was drowned. Brendan offers to pray for the giant, and to beg God to revive him so that he may be baptized. Once that is done, the giant may even, if he lives to praise God, find forgiveness for his sins, and eventually ascend to paradise. The giant refuses; his is afraid that in his new life he might not be able to withstand the temptation of sin. What if he started robbing again? He would be a lot worse off then as, according to the giant, Christians are punished much more severely in hell than pagans. Moreover, the prospect of having to suffer the pain of death as second time frightens him. He wants to go back to his torments / poor companions in the place of darkness. He departs with Brendan’s best wishes. Brendan then proceeds on his way.

BLACK ANGUS AND THE SAINT

The Works of Fiona Macleod, Volume IV, Iona

Elsewhere I have told how a good man of Iona sailed along the coast one Sabbath afternoon with the Holy Book, and put the Word upon the seals of Soa: and, in another tale, how a lonely man fought with a sea-woman that was a seal: as, again, how two fishermen strove with the sea-witch of Earraid: and, in “The Dan-nan-Ron,” of a man who went mad with the sea-madness, because of the seal-blood that was in his veins, he being a MacOdrum of Uist, and one of the Sliochd nan Ron, the Tribe of the Seal. And those who have read the tale, twice printed, once as “The Annir Choille,” and again as “Cathal of the Woods,” will remember how, at the end, the good hermit Molios, when near death in his sea-cave of Arran, called the seals to come out of the wave and listen to him, so that he might tell them the white story of Christ; and how in the moonshine, with the flowing tide stealing from his feet to his knees, the old saint preached the gospel of love, while the seals crouched upon the rocks, with their brown eyes filled with glad tears: and how, before his death at dawn, he was comforted by hearing them splashing to and fro in the moon-dazzle, and calling one to the other, “We, too, are of the sons of God.”

What has so often been written about is a reflection of what is in the mind: and though stories of the seals may be heard from the Rhinns of Islay to the Seven Hunters (and I first heard that of the MacOdrums, the seal-folk, from a Uist man), I think, that it was because of what I heard of the sea-people on Iona, when I was a child, that they have been so much with me in remembrance.

In the short tale of the Moon-child, I told how two seals that had been wronged by a curse which had been put upon them by Columba, forgave the saint. and gave him a sore-won peace. I recall another (unpublished) tale, where a seal called Domnhuil Dhu—a name of evil omen—was heard laughing one Hallowe’en on the rocks below the ruined abbey, and calling to the creatures of the sea that God was dead: and how the man who heard him laughed, and was therewith stricken with paralysis, and so fell sidelong from the rocks into the deep wave, and was afterwards found beaten as with hammers and shredded as with sharp fangs.

But, as most characteristic, I would rather tell here the story of Black Angus, though the longer tale of which it forms a part has been printed before.

One night, a dark rainy night it was, with an uplift wind battering as with the palms of savage hands the heavy clouds that hid the moon, I went to the cottage near Spanish Port, where my friend Ivor Maclean lived with his old deaf mother. He had reluctantly promised to tell me the legend of Black Angus, a request he had ignored in a sullen silence when he and Padruic Macrae and I were on the Sound that day. No tales of the kind should be told upon the water.

When I entered, he was sitting before the flaming coal-fire; for on Iona now, by decree of MacCailein Mòr, there is no more peat burned.

“You will tell me now, Ivor?” was all I said.

“Yes; I will be telling you now. And the reason why I never told you before was because it is not a wise or a good thing to tell ancient stories about the sea while still on the running wave. Macrae should not have done that thing. It may be we shall suffer for it when next we go out with the nets. We were to go to-night; but, no, not I, no, no, for sure, not for all the herring in the Sound.”

“Is it an ancient sgeul, Ivor?”

“Ay. I am not for knowing the age of these things. It may be as old as the days of the Féinn, for all I know. It has come down to us. Alasdair MacAlasdair of Tiree, him that used to boast of having all the stories of Colum and Brigdhe, it was he told it to the mother of my mother, and she, to me.”

“What is it called?”

“Well, this and that; but there is no harm in saying it is called the Dark Nameless One.”

“The Dark Nameless One!

“It is this way. But will you ever have heard of the MacOdrums of Uist?

“Ay; the Sliochd-nan-ròn.

“That is so. God knows. The Sliochd nan-ròn . . . the progeny of the Seal. . . . Well, well , no man knows what moves in the shadow of life. And now I will be telling you that old ancient tale, as it was given to me by the mother of my mother.”

On a day of the days, Colum was walking alone by the sea-shore. The monks were at the hoe or the spade, and some milking the kye, and some at the fishing. They say it was on the first day of the Faoilleach Geamhraidh, the day that is called Am Fhéill Brighde, and that they call Candlemas over yonder.

The holy man had wandered on to where the rocks are, opposite to Soa. He was praying and praying; and it is said that whenever he prayed aloud, the barren egg in the nest would quicken, and the blighted bud unfold, and the butterfly break its shroud.

Of a sudden he came upon a great black seal, lying silent on the rocks, with wicked eyes.

“My blessing upon you, O Ròn,” he said, with the good kind courteousness that was his. “Droch spadadh ort,” answered the seal, “A bad end to you, Colum of the Gown.”

“Sure now,” said Colum angrily, “I am knowing by that curse that you are no friend of Christ, but of the evil pagan faith out of the north. For here I am known ever as Colum the White, or as Colum the Saint; and it is only the Picts and the wanton Normen who deride me because of the holy white robe I wear.”

“Well, well,” replied the seal, speaking the good Gaelic as though it were the tongue of the deep sea, as God knows it may be for all you, I, or the blind wind can say; “well, well, let that thing be: it’s a wave-way here or a wave-way there. But now, if it is a druid you are, whether of fire or of Christ, be telling me where my woman is, and where my little daughter.”

At this, Colum looked at him for a long while. Then he knew.

“It is a man you were once, O Ron?”

“Maybe ay and maybe no.”

“And with that thick Gaelic that you have, it will be out of the north isles you come?”

“That is a true thing.”

“Now I am for knowing at last who and what you are. You are one of the race of Odrum the Pagan?”

“Well, I am not denying it, Colum. And what is more, I am Angus MacOdrum, Aonghas mac Torcall mhic Odrum, and the name I am known by is Black Angus.”

“A fitting name too,” said Colum the Holy, “because of the black sin in your heart, and the black end God has in store for you.”

At that Black Angus laughed.

“Why is the laughter upon you, Man-Seal?”

“Well, it is because of the good company I’ll be having. But, now, give me the word: Are you for having seen or heard of a woman called Kirsteen M’Vurich?”

“Kirsteen—Kirsteen—that is the good name of a nun it is, and no sea-wanton!”

“O, a name here or a name there s soft sand. And so you cannot be for telling me where my woman is?”

“No.”

“Then a stake for your belly, and nails through your hands, thirst on your tongue, and the corbies at your eyne!”

And, with that, Black Angus louped into the green water, and the hoarse wild laugh of him sprang into the air and fell dead upon the shore like a wind-spent mew.

Colum went slowly back to the brethren, brooding deep. “God is good,” he said in a low voice, again and again; and each time that he spoke there came a daisy into the grass, or a bird rose, with song to it for the first time, wonderful and sweet to hear.

As he drew near to the House of God he met Murtagh, an old monk of the ancient race of the isles.

“Who is Kirsteen M’Vurich, Murtagh?” he asked.

“She was a good servant of Christ, she was, in the south isles, O Colum, till Black Angus won her to the sea.”

And when was that?”

“Nigh upon a thousand years ago.”

“But can mortal sin live as long as that?”

“Ay, it endureth. Long, long ago, before Oisin sang, before Fionn, before Cuchullin, was a glorious great prince, and in the days when the Tuatha-de-Danann were sole lords in all green Banba, Black Angus made the woman Kirsteen M’Vurich leave the place of prayer and go down to the sea-sbore, and there he leaped upon her and made her his prey, and she followed him into the sea.”

“And is death above her now?”

“No. She is the woman that weaves the sea-spells at the wild place out yonder that is known as Earraid: she that is called the seawitch.”

“Then why was Black Angus for the seeking her here and the seeking her there?”

“It is the Doom. It is Adam’s first wife she is, that sea-witch over there, where the foam is ever in the sharp fangs of the rocks.”

“And who will he be?”

His body is the body of Angus, the son of Torcall of the race of Odrum, for all that a seal be is to the seeming; but the soul of him is Judas.”

“Black Judas, Murtagh?”

“Ay, Black Judas, Colum.”

But with that, Ivor Macrae rose abruptly from before the fire, saying that he would speak no more that night. And truly enough there was a wild, lone, desolate cry in the wind, and a slapping of the waves one upon the other with an eerie laughing sound, and the screaming of a seamew that was like a human thing.

So I touched the shawl of his mother, who looked up with startled eyes and said, “God be with us”; and then I opened the door, and the salt smell of the wrack was in my nostrils, and the great drowning blackness of the night.

<< Home