Out and Down, Around and Ground

THE POEM AS CORACLE

AND DIVING BELL

June 27

There, there is nothing else

but grace and measure

Richness, quietness, and pleasure.

-- Baudelaire, “L’Invitation Du Voyage”

This crossing and descending

line both travels and rappels,

extending toward shores

& descending to bottoms

neither yet dreamed of in the

catalogue. I sail; I dive;

I keep the pulse alive

by finding surf-hallowed

ground at the same

time harrowing the

deeper leagues of what I find.

There are ports

which drift and dream

all night of shores

too far to reach, bobbing

all the boats tied there

with swells of sweetest

far-shore booty--

gold chapels, moon

castles, white

birds choralling God

on trees which take

up islands, steaming

plates of meat and

ardor laid out on tables

which no human

hands have cooked.

Also there are salt

Vaginas in the sound of

those far crash-

and booming waves,

the welcome of farewells,

an invitation to travel

down the deepest brines

of the heart, mines of

pure abyss darker and

wilder than any kiss

than I have known.

But will, this dark,

rain-sotted morning insists,

wafting lucent cleavage

in the next blue door

I find as the song gets

down under occluding

riven basics like I to

Thou and other glints

Of surficial seem.

Thus I peruse the ages

and carouse the beds,

dislodge gold psalters

from beneath the sleeping

head of a great blue

dragon circled round

the next island in the main,

a wild not found on

any chart on any ship

except the one inside

my dream. I voyage forth

to froth and foam

past all marges

to the sea god’s throne:

I dive deep along the

descending mile of

the iceberg, tracing

that god’s frozen bones

to where the poem’s

heel at last strikes

his own in the basalt

lingua of first things.

Such motions keep me

square on an unrelenting

thrash of ocean, level

between island and doom,

exceeding both coracle

and bell which tolls the

lees of hell.

From Navigatio sancti Brendani abbatis (“The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbott”), transl. Denis O’Donoghue, 1893:

St Brendan then embarked, and they set sail towards the summer solstice. They had a fair wind, and therefore no labour, only to keep the sails properly set; but after twelve days the wind fell to a dead calm, and they had to labour at the oars until their strength was nearly exhausted. Then St Brendan would encourage and exhort them: ‘Fear not, brothers, for our God will be unto us a helper, a mariner, and a pilot; take in the oars and helm, keep the sails set, and may God do unto us, His servants and His little vessel, as He willeth.’. They took refreshment always in the evening, and sometimes a wind sprung up; but they knew not from what point it blew, nor in what direction they were sailing.

At the end of forty days, when all their provisions were spent, there appeared towards the north, an island very rocky and steep. When they drew near it, they saw its cliffs upright like a wall, and many streams of water rushing down into the sea from the summit of the island; but they could not discover a landing-place for the boat. Being sorely distressed with hunger and thirst, the brethren got some vessels in which to catch the water as it fell; but St Brendan cautioned them: ‘Brothers! do not a foolish thing; while God wills not to show us a landing-place, you would take this without His permission; but after three days the Lord Jesus Christ will show His servants a secure harbour and resting-place, where you ‘may refresh your wearied bodies.’

When they had sailed round the island for three days, they descried, on the third day, about the hour of none, a small cove, where the boat could enter; and St Brendan forthwith arose and blessed this landing-place, where the rocks stood on every side, of wonderful steepness like a wall. When all had disembarked and stood upon the beach, St Brendan directed them to remove nothing from the boat, and then there appeared a dog, approaching from a bye-path, who came to fawn upon the saint, as dogs are wont to fawn upon their masters. ‘Has not the Lord,’ said St Brendan, ‘sent us a goodly messenger; let us follow him;’ and the brethren followed the dog, until they came to a large mansion, in which they found a spacious hall, laid out with couches and seats, and water for washing their feet, ‘When they had taken some rest, St, Brendan warned them thus: ‘Beware lest Satan lead you into temptation, for I can see him urging one of the three monks, who followed after us from the monastery, to a wicked theft. Pray you for his soul, for his flesh is in Satan’s power.’

The mansion where they abode had its walls hung around with vessels made of various metals, with bridle--bits and horns inlaid with silver,

St Brendan ordered the serving brother to produce the meal which God had sent them; and without delay the table was laid with napkins, and with white loaves and fish for each brother, When all had been laid out, St Brendan blessed the repast and the brethren: ‘Let us give praise to the God of heaven, who provideth food for all His creatures.’ Then the brethren partook of the repast, giving thanks to the Lord, and took likewise drink, as much as they pleased. The meal. being finished, and the divine office discharged, St Brendan said: ‘Go to your rest now; here you see couches well dressed for each of you; and you need to rest those limbs over-wearied by your labours during our voyage. ‘

When the brethren had gone to sleep, St Brendan saw the demon, in the guise of alittle black boy, at his work, having in his hands a bridle-bit, and beckoning to the monk before mentioned: then he rose from his couch, and remained all night in prayer.

When morning came the brethren hastened to perform the divine offices, and wishing to take to their boat again, they found the table laid for their meal. as on the previous day; and so for three days and nights did God provide their repasts for His servants.

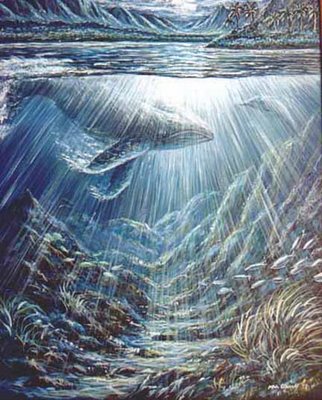

In the “The Honor and Glory of Whaling” chapter of Moby Dick, Melville transforms his lateral, linear sea-tale into something deeper, sinking his American gnostic gospel to its true end in the depths, as the Pequod will dive after Moby Dick at the story’s end.

“The more I dive into this matter of whaling,” he writes in the chapter, “and push my researches up to the very spring-head of it, so much the more am I impressed with its great honorableness and antiquity; and especially when I find so many great demi-gods and heroes, prophets of all sorts, who one way or other have shed distinction upon it.”

Melville then ranges through a variety of mythic whale-sized endeavors, from Perseus freeing Andromeda from Leviathan to Jonah spending three nights in a whale, Hercules battling his way out of one and St. George fighting the Dragon (offering that whales and dragons were often confused, and quotes Ezekiel: “Thou art as a lion of the waters, and as a dragon of the sea”).

Yet that is not enough: his greatest effort calls for an even more fundamental source. So he writes,

“Nor do heroes, saints, demigods and prophets alone compose the whole roll of our order. Our grand master is till to be named, for like royal kings of old times, we find the headwaters of our fraternity in nothing short of the great gods themselves. That wonderful oriental story is now rehearsed from Shaster, which gives us the dread Vishnoo, one of the three persons in the godhead of the Hindoos; gives us this divine Vishnoo himself for our Lord; — Vishnoo, who, by the first of his ten earthly incarnations, has for ever set apart and sanctified the whale.

“When Bramha, or the God of Gods, saith the Shaster, resolved to recreate the world after one of its periodic dissolutions, he gave birth to Vishnoo, to preside over the work; but the Vedas, or mystical books, whose perusal would seem to have been indispensible to Vishnoo before beginning the creation, and which must have contained something in the shape of practical hints to young architects, these Vedas were lying at the bottom of the waters; so Vishnoo became incarnate as a whale, and sending down to the uttermost depths, rescued the sacred volumes. Was not this Vishnoo a whalemen, then? ever as a man rides a horse is called a horseman?”

TWO DOOMS

June 28

I don’t know which deep-

sea image thralls me more:

The once-held notion

that ships & whales &

drowned men float

forever at the league

whose pressure finally

resists their falling weight;

or the later fact that

all things fall down the sea

until they lay at rest

at the bottom of it all.

As tropes go, each

unfurls bright sails

of welcome to the breeze,

lifting and crashing

the poem’s bow over a

wild blue wake startling

for what it travels toward

as reveals so far below.

In the first I see an

afterlife of angels in their zones,

hierarchons of salt abyss

stationed according to

their mass -- first the wide-eyed

men with arms still open

to the flinging of their souls;

then the halves of ships

with broken masts afloat

upon tides too dark for hearts

to see; and then, still further

down, the spiralling gavotte

of dead whales round the seas,

eternally at rest where

they once jawed squid

and spat their offspring

between a hell-dam’s knees.

In the second I read it takes

about three days to fall

all the way down deepest seas,

a nekyia like Christ’s three

days’ walk through Hell,

or St. Oran’s voyage to

Manannan’s north down

the well in which he was

buried in beneath the Iona

abbey’s footers. Three days

and nights to harrow down

the leagues of doom, to reach

at last the country of the

lost and tossed and damned,

a Sidhe-mound of spilled

doubloons and whale hips

and the teeth of dinosaur

divas not seen in seas for

three hundred million years.

It’s all there amid the

trash of a billion year

dreamtime falling, falling,

falling that way. How deep

is that infernal loam, I wonder,

across an acreage which

takes up three quarters of

this globe, a bricolage too

thick to read with all

sorts of endings sticking

out, a mast, a pocket

watch, the eyehole

of Manannan’s huge skull

like a door to mansions

further down?

To float -- or fall?

I’d hire ‘em both

to keel these lines

with the two darkest

lumbers in the sea,

ends which tantalize

the greenhorn pen

to leave behind dry chores

and seek those crashing shores

where all ships convoy out

beyond the metres of the known,

all eyes on deck riveted on

the dream of far adventure

with fear in its undertow,

repasting on the soul for dinner.

The great ships roll

proud and blowsy between

the awe and awfulness,

careering every wilderness

to find the greater shore,

even when it’s one or

three miles further down

from the softest beds

of island girls who

stain their lips with juice.

Two ends of falling

delight as they appall,

harrowing with depths

far wilder than the shores

of the farthest maidenhead

of all: and which, I wonder,

is the truest skipper of the dream:

the ever-drifting Yes of No

or the final failing scream?

<< Home