Ogres On The Road

... Less than a billow of the sea

That at the last do no more roam,

Less than a wave, less than a wave,

This thing that hath no home,

This thing that hath no grave ...

-- Fiona MacLeod, “In the Night”

TRINITY

2004

Three fins weave this

wave from heart to hand

to page where your eyes shore;

consubstantial, male in

their martial quest for

affect, like the three kings

of Orient who ride their

camels slowly across

the starry desert, each

a third aspect, all pulsing

the obligatos of Empire.

First there is my greed

for sexual plunder, slick

and raw and urgent,

that bell which bears

a tight-balled ache to

hurl the next name of God.

Then there is the voyager

who never gazed at

a margin that he didn’t

wish to escape; his compass

is much different from the

first, pointing just beyond

the beloved toward the

angels she occludes.

Finally, there is the one

with molting wings who

refuses to call this

anything but calling;

he tends a font of quintessential

blue that isn’t blue at all

but sings the blues of it,

the way the ocean is not

blue but heaves great

dreams of blue on every

summer shore. Three

glands ooze their salt

mercurials into the

perplex ardor of this next

poem, rising from one great

body buried deep in me:

Cerne Giant, Oran in

his bone coracle, and

some Shakespearean wog

sawing a Dantean rag

on his bluey violin. Three

tenors warble center

stage of this hall of song,

belting out a three-part

harmony this next poem long.

***

Finally, rains of their own accord, a midmorning mist segueing into harder spiculations, the urgency of the torrent, slathering all with desperately needed moisture ... so there’s a suck to the Sunday, a receipt around and about and down the usual rituals of mowing, cleaning, ironing, cooking, recalibrating the being for the work week. A watered being, refreshened from an aquifer I call my giant past ...

A meditation here on the background of the hero. What he quests, he is, in some former sense, and the progression of his tale is regression, heading into wider and wilder steppes of the dream. Each test heightens the quandary of ego and Self: the weapons which the hero march off with work in the first battles yet are increasingly of no use in the subsequent ones.

Take, for instance, the figure of the giant which the hero encounters. It is one thing to meet and best the ogre on the road; it is another thing to tackle with his mother, a far older and menacing matrix (her jaws open wide beneath us); its is a third thing to enter the lair of the dragon, the oldest figure in this trio of encounters, the third apocalyptic embrace of the hero with his Self. Well, apocalyptic to the ego, because it knows it cannot resist or best the transformation about to take place.

To progress in the tale is to regress to its sources; the next figure on the road is the background of the former. In Iona, Fiona MacLeod traces this course back down in the lineage of St. Michael:

***

The “Iollach Mhicheil” — the triumphal song of Michael — is quite as much pagan as Christian. We have here, indeed, one of the most interesting and convincing instances of the transmutation of a personal symbol. St. Michael is on the surface a saint of extraordinary powers and the patron of the shores and the shore-folk; deeper, he is an angel, who is upon the sea what the angelical saint, St. George, is upon the land: deeper, he is a blending of the Roman Neptune and the Greek Poseidon: deeper, he is himself and ancient Celtic god: deeper, he is no other than Manannan, the god of ocean and all waters, in the Gaelic pantheon: as, once more, Manannan himself is dimly revealed to us as still more ancient, more primitive, and even as supreme in remote godhead, the Father of an Immortal Clan.

***

1. THE OGRE ON THE ROAD

Katherine Briggs writes in The Fairies in Tradition and Folklore

Often monstrous traits are attached to heroes, who sometimes seem to have changed from gods to heroes and from heroes to giants. In a learned and penetrating article in Volume 69 of Folklore, Dr. Ellis Davidson has examined the connection between Wade and Weland, and the beliefs we can deduce from various fragments of the story. It well illustrates the connections between the fairies, the giants, and the dead. In the course of the paper she says:

“Behind the figure of Weland the Smith it seems possible to discern a race of supernatural beings thought of in general as giants (but related also to dwarves and elves), who are both male and female, who live in families, who are skilled at the making of weapons and at stone-building, and whose dwellings may be reached by a descent into the earth of under-water. Wad and Weland are possibly Grendel also. The local traditions of giants who dwell in mounds, caves or stone tombs are of great interest, and Sir Gawain’s Green Knight should perhaps be added to the list.” (H.R. Ellis Davidson, “Weland the Smith,” Folklore Vol 69, 145-59)

(She continues:)

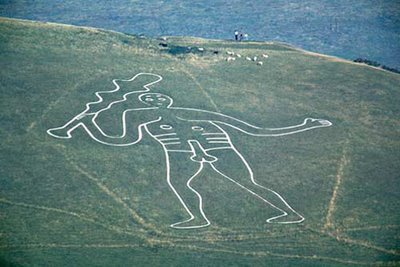

Occasional hill figures, like that at Cerne Abbas, or the Long Man of Wilmington, have generally gathered some kind of vague giant story to them, whatever their origin may have been. So the Cerne Abbas figure is supposed to be the outline of a giant killed by the local people as he slept a gorged sleep after eating their cattle. (see J.S. Udal, Doreshire Folk-Lore, Hertford, 1922, 154-8)

***

GIANT

June 15

Abbas Cerne was cut from chalk

where all the men had killed him,

sleeping on mountain sward

deep in the glut of slaughter.

His six-foot penis still glistens

with moon and sea and wombs

our wives will never speak of

though they smile faintly

when they dream. When he

walked his shoulders cleared

the highest ridges, his feet

connected villages in one stride.

He could stand far out at sea

with his head above the crests

like a darker-browed island,

his smile widening in mist

as he devoured errant ships.

And oh the hauls spilled

from his net, filled with

mackerel as large as bulls,

narwhals and sea-lions,

parcels of sea-treasure

too, fat chests of gold,

barrels of wild whiskey

still corked tight as

a nun’s hoo-ha, steeples

with bells not heard

on land for a thousand

years. It’s said he lived

down there, at the ass-

end of all seas where

dead sailors and lost gods

drift their fabled bones.

His abbey was in

a long-drowned town

and it was piled high

with verboten books

where every lost secret

has been bound, salt

liturgies now ebbed away,

tales of heroes too tall

for skeptic ears, spells for

spinning castle doors

and love-potions for

the maidenheads of kings

who battle and fell beneath

far huger moons of old,

wide as the sea and

gibbous in a heart

blue-blacker than the

one we’ve come to

call our own. His haunt

is drowned by the

thousand leagues of time

down which all tales fall

from ferocity to gleam

to broad shouldered shades

fading yet further down

to a certain ache of absence

which arches back in

welcome when a fragment

of his tale washes up

on this first shore.

A certain wave reveals

in its curved crash

a phosphor of a dream,

reminding us that he’s

still there in ghost relief,

chalk father of the psyche

we married. Oh and

that cock of his

was immense and

unmerciful as the sea,

thick as a drunk tongue

and as long as we are

buried when we’re

planted back into his loam.

My love of tall tales

strides with him out there

on that moony sea; the

wave rider of my song

is just his merry brow;

the singing of the topside

man arises from lungs

of heaving brine and silt

and tides like deep waves

across a basso clef

pure cliff to billowed abyss.

Sing down with me

in his beclouded jisms

of divine ferocity and tooth,

a wut or singing hut

of infernal holiness, eternal

sot and sate and murder

on green fields. He’s no more

me than the pen I her rage

though I sing of him as

hard and deep as I can,

my hand thus a colossal

striding profane man

who totems the singer’s clan,

whose salt-abbey I man

re-scribing all its manuscripts,

verse by spell by rann.

THE OGRE ON THE SHORE

2004

Too much of water hast thou, poor Ophelia.

-- Laertes, Hamlet

As always, my history assumes Your

mystery, insolving seas inside

my mother’s voice that day

she sang over silk-bruited waves.

She and it You meant to pair

on a shore of such narrow degree

that one step right or left

was either witchery or knowledge,

both doomed to boil my bones.

The ogre on the road of souls

may loom close to my father’s height

inside the doors I cannot pass;

surely the monster got

his basso and berserker cock

from my six-year-old’s lack

and reverence of such things;

but he is not there at every

crossroads to mentor me

in song, even though

he’s Poetry and more. Redder

jousts than sweet psalmody

are in his throat, and I’m a fool

to margin all he ravages

and cancels out. Not by Providence

but Victory! the fish-man shouts

astride exultant waves, smashing

every naked shore with the his

uncleffed, sperm-gout gore.

How else can I say it? There is

my father’s dream or vision

of meeting Thor on the northern-

most wild of Iona years ago,

turning from his history

to face that huge churl of

Hebridean gale, the soul

of every rock-browed cliff

devoured by wind and wave.

Was it passion that burst

my father’s heart in love

for that sworded knight of

Northern winds? Was that

first song hot enough to

bid my father turn his gaze

back round to Pennsylvanian

velds where he pried and set

god’s hoar skeleton stone by

cold-ribbed stone? Or was it

enough of the second

song which does not huff and blow

the footers down in any

appeasable way but is wind itself,

unmixed of any abbey’s mortared mould,

defiant even of the words themselves?

Must I thus proceed?

How to build a chapel fit

to sing of him whom pronouns quit,

who is instead that dancing fit

which spirals sea and sky?

Build on water, yes; but tower

in no wise semblant to the backward

glance which mints its empire

on a selfish penury, a dime a dance,

vaulting the dervish in mere pedigree,

my resume which overwrites the mystery

into the majescule of history,

nippling seas and crowning winds.

Oh the shore is ever dangerous

which walks between dominions:

Not to drown or fully ebb

nor even say which sands I stride on

—not quite a page, nor sheeted

from that windy rage which grinds

the mortal shell of the earth

to infinitesimals of cosmic dust.

And we just oxidizers and rust,

corrosive as the salty seas,

& uncoagulent as loosened skies,

never one but many throats

professing gorgeous dooms

every time a wave curls high

and rides the poem to hell

down one long choiring boom.

In the Christian era, the saints kept bumping up against their forefathers’ bones, which were usually collossal. s. Heavy upon them was the burden or quest of saving their ancestors from the mortal sin of pagan sooth.

The Life of Colum Cille (Columba), written in Irish by Manus O'Donnell and written in 1532, contains the following episode:

"Once when Colum Cille was walking beside the river Boyne a human skull was brought to him. The size of the skull was much bigger than the skulls of the people of that time. Then his followers said to Colum Cille, "It is a pity we don't know whose skull this is, or the whereabouts of the soul that was in the body on which it was." Colum Cille answered, "I'm not leaving this place until I find this out from God for you."

"Then Colum Cille prayed earnestly to God for that to be revealed to him, and God heard that prayer so that the skull itself spoke to him. It said that it was the skull of Cormac mac Airt, son of Conn of the Hundred Battles, king of Ireland, and an ancestor to himself, for Colum Cille was tenth generation after Cormac. And the skull said that although his faith wasn't perfect, he had a certain amount of faith and, because of his keeping the truth and that as God knew that from his descendants would come Colum Cille who would pray for his soul, He had not damned him permanently, although it was in severe pain that he awaited these prayers.

"Then Colum Cillle picked up the skull and washed it honorably, and baptized and blessed it; then he buried it. And Colum Cille did not leave that place until he had said 30 masses for the soul of Cormac. And at the last of the masses, the angels of God appeared to Colum Cille, taking Cormac's soul with them to enjoy eternal glory through the prayers of Colum Cille."

- O'Donnell, The Life of Colum Cillle, transl. B. Lacey, Dublin 1998

***

THE HEATHEN GIANT

Feb. 2005

(In episode 4 of The Voyage of St. Brendan) Brendan, having had a ship built for him, finds the exceptionally large head of a dead man on the beach. Its forehead measures five feet across. When Brendan asks what kind of life he has led, the man’s head answers that he was a hundred feet tall and very strong. He was a heathen who waded through the sea to rob ships. This he did for a living. In a heavy storm which whipped up the waves to extreme heights he was drowned. Brendan offers to pray for the giant, and to beg God to revive him so that he may be baptized. Once that is done, the giant may even, if he lives to praise God, find forgiveness for his sins, and eventually ascend to paradise. The giant refuses; his is afraid that in his new life he might not be able to withstand the temptation of sin. What if he started robbing again? He would be a lot worse off then as, according to the giant, Christians are punished much more severely in hell than pagans. Moreover, the prospect of having to suffer the pain of death as second time frightens him. He wants to go back to his torments / poor companions in the place of darkness. He departs with Brendan’s best wishes. Brendan then proceeds on his way.

-- Clara Strijbosch, The Seafaring Saint

The old nights lay like massive bones

scattered on the beach, the skull

like a split moon buried in the sand.

Sea-sounds through its occiput

are the voices of memory, faint

and ghastly as the depths I once

fell to find you in the darkest

beds of sweet abyss. He remembers

the feral heart of old, icy and

on fire for plunder, parting thighs

with blue gusto & launching his

dragon ship there with the pith

and pitch of awfulness,

rowing voices crowing one pent

dragon seethe. Eye-sockets big

as church-doors retain the marrow

of those nights, their dark abcessa

still lucent, even lewd, harrows which

invite the next arriving saint to

find a heaven wide enough to

revive and save a soul so massive,

old and hungry. But he will not

rise again, not for all the pearly

virginettes bent in heaven’s

puffy marge. Wholly dark now, he

strides between this beach and

those dark nights, sporting

in a sea of finned and ghostly

salt delights, unrepentant

as my backwards glance which

call his life and ways both holy.

I appoint that house of bleached

ribs apt chapel of the wilder

half of my heart and God’s and

yours, you who would embrace

the seven seas to slake

your womb’s blue belling need.

SKULL MUSIC

2004

My head is also Yours, rude stone,

Bone petra: A vault of verbal

Coins and blue booty, the old slush

Pile of all my days and what You

Make of them. I now believe that

Each event enfolds three cups here:

The tale, its bedding, and the dream

It opens like a door. It’s no

wonder that skulls were set in the

Lintels of barrows, and pitched down

Wells. Nor that I’ve found so many

Here. Each poem is but a tongue both

Back and forward of Your own, my

Totem father, my old stone cross.

May Your bone summit bless this toss.

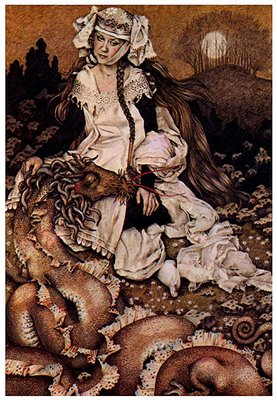

2. GRENDEL’S DAM

They went to sleep. And one paid dearly

for his night’s ease, as had happened to them often,

ever since Grendel occupied the gold-hall,

committing evil until the end came,

death after his crimes. Then it became clear,

obvious to everyone once the fight was over,

that an avenger lurked and was still alive,

grimly biding time. Grendel’s mother,

monstrous hell-bride, brooded on her wrongs.

She had been forced down into fearful waters,

the cold depths, after Cain had killed

his father’s son, felled his own

brother with a sword. Branded an outlaw,

shunned company and joy. and from Cain there sprang

misbegotten spirits, among them Grendel,

the banished and accursed, due to come to grips

with that watcher in Heorot waiting to do battle.

The monster wrenched and wrestled with him

but Beowulf was mindful of his mighty strength,

the wondrous gifts God had showered on him:

He relied for help on the Lord of All,

on His care and favour. So he overcame the foe,

brought down the hell-brute. Broken and bowed,

outcast from all sweetness, the enemy of mankind

made for his death-den. But now his mother

had sallied forth on a savage journey,

grief-wracked and ravenous, desperate for revenge.

-- Beowulf, 1251-78, transl. Seamus Heaney

***

DAM

June 17

If you think sons Grendel

Cerne & Caliban were bad,

try stepping back into their

moms, those giant dams of

heart so hot with Hekatean

spleen you’d think their wombs

were lava casks, fountains

of deranging ire. Beowulf dove

in the mere to have it out

with she who nursed Grendel

on blue gall, who after the

son was dispatched became

the greater hurt of Heorot,

a fen of gore-dripping jaws.

At the bottom of the lake

the hero met the mama

and battled in a swallowed

court where body parts still

drifted about the abysmally

dark pall, the witched waters

almost too deep and drear

for Beowulf’s greatest test

which he would yet survive.

(The third test with the worm

went back, sadly, too far.)

The Cally berry of Ulster

would fly over the heights

in the thick of night

with Cerne’s big balls

bound in her skirt, tonnish

boulders which she ferried

far to build a mobile

court, the castle which

moves every night from

one man’s dream to

the next. And then there’s

Sycorax, the prioress

of Shakespeare’s final isle,

gone when the tale begins, her

rude magic rough in Properero’s

hands, leeched in his book

of charms, her ancient

darkness washing against

the play like tides

against the island’s shores,

haunting every line.

These dames don’t fuck

around, if you know

what I mean; or they

do and wildly so,

off every psalter page,

deep down beneath

the bleaching altars of

the male god’s history

when his loins and

hands were colossal

havocs of libido

cockstrutting across

the earth. Behind

every of those big lugs

there’s a dam, a walled-

off lake of fire whose

womb is bottomless,

whose will cements

her sons into Green Chapels

of headless rapine

and sea-wide ravages.

In her name those giants

wreak havoc on the

later realm, like adulterated

children of the booze,

drowning all they touch

dementing every kiss with

fire. The father in those

old tall tales can never

quite be found, much less

named, though he’s a bastard

to be sure, god in his

nth iniquity, saddled to

his black hips and armed

with dragon’s teeth. He

broke in one night

and had his way with

her (who once was young

and beautiful, betrothed

to kings of men) -- Had

his way with her all night,

fucking her so hard

and deep as to pockmark

the very moon with

gouges and crevasses

amid tranquil seas

of hurled sperm. The

son she bore was her

revenge on the

eviction of her rule

by men more conscious

than they dared

or knew was death to try.

Up from the fens

and moors she sent

her monster son,

and when he fell to

knights and priests

she washed out from

the tide, a fell

malignant tree-sized

thing no sword has

ever touched, nor

gospel ever quelled.

I leave her rasping

at the door outside

at the hag ends of

this poem’s hour,

a pent growl of a purr

with every claw distended

one inch from coming through.

Say what you will of

her but only mud and fire

will do to see her standing

there outside my writing

room, an invitation

to the dance and die

amid the echoes of salt doom.

***

GIANTESS

I am Cupid’s WMD, a

Catapult of blue breasts. The skulls

Of my scooped-out lovers line the

Mazes of my cave, far beneath

The rolling sea. By day I dream

Of your cock and balls in this mouth

Of stone; by night I feed, tapping

O so gently my suckered limbs

Against your window panes, calling

You out to drown my way. My rule

Has lasted here some four hundred

Million years, yet every dusk which

Darkens abyss I wake afresh,

Starved wet in uncoiling desire,

Beak snapping for your milk of fire.

-- In an article in Geology 28, L. Piccard finds tectonic roots for Grendel’s mam:

A multidisciplinary study reveals close correspondences between mythological descriptions, arrangement of the cult-sites and local active faults in ancient Greece (Piccardi, 2000a and 2000b). Chthonic dragons, mostly feminine polymorph creatures, were also indicated at many of these special sacred places, and their lairs are located directly above major active faults (Piccardi, 2000c). The veneration of these places might have been a consequence of the observation of peculiar natural phenomena, such as gas and flames emissions, underground roaring, ground shaking and ground ruptures. Maybe this coincidence is simply circumstantial in the East Mediterranean due to the abundance of myths in such a highly seismic region. However, it can likewise be observed in areas less active seismically, and with different mythologies. Scotland, for example, is famous for its modern myth of the Loch Ness monster, affectionately called Nessie. Known to derive from a primitive cult of the water-horse, sacred to the Picts, its first written mention appears in Adomnan's 'Life of St. Columba' (7th century AD). In the original Latin description the dragon appears "cum ingenti fremitu" (with strong shaking), and disappears "tremefacta" (shaking herself), which seems to point to a telluric nature of the monster living in the lake. In fact, Loch Ness is positioned directly over the fault zone of the most seismic sector (for example the M=5 earthquake of 18.09.1901) of the Great Glen Fault, the major active fault in Scotland. In this light, many modern eyewitness reports attributed to Nessie may find a simple natural explanation.

-- “Active faulting at Delphi: seismotectonic remarks and a hypothesis for the geological environment of a myth.” Geology, 28, 651-654.

****

Jung frames the giantess as the mother and consort of the giant whom the hero first encounters, a greater door to the inner dark. He writes in a 1932 article on Picasso:

...When I say 'he,' I mean that personality in Picasso which suffers the underworld fate - the man in him who does not turn towards the day-world, but is fatefully drawn into the dark; who follows not the accepted ideals of goodness and beauty, but the demoniacal attraction of ugliness and evil. It is these antichristian and Luciferian forces that well up in modern man and engender an all-pervading sense of doom, veiling the bright world of day with the mists of Hades, infecting it with deadly decay, and finally, like an earthquake, dissolving it into fragments, fractures, discarded remnants, debris, shreds, and disorganized units. Picasso and his exhibition are a sign of the times, just as much as the twenty-eight thousand people who came to look at his pictures.

When such a fate befalls a man who belongs to the neurotic, he usually encounters the unconscious in the form of the 'Dark One,' a Kundry of horribly grotesque, primeval ugliness or else of infernal beauty. In Faust's metamorphosis, Gretchen, Helen, Mary, and the abstract 'Eternal Feminine' correspond to the four female figures of the Gnostic underworld, Eve, Helen, Mary, and Sophia. And just as Faust is embroiled in murderous happenings and reappears in changed form, so Picasso changes shape and reappears in the underworld form of the tragic Harlequin - a motif that runs through numerous paintings. It may be remarked in passing that Harlequin is an ancient chthonic god.

The descent into ancient times has been associated ever since Homer's day with the Nekyia. Faust turns back to the crazy primitive world of the witches' sabbath and to a chimerical vision of classical antiquity. Picasso conjures up crude, earthy shapes, grotesque and primitive, and resurrects the soullessness of ancient Pompeii in a cold, glittering light - even Giulio Romano could not have done worse!

Seldom or never have I had a patient who did not go back to neolithic art forms or revel in evocations of Dionysian orgies. Harlequin wanders like Faust through all these forms, though sometimes nothing betrays his presence but his wine, his lute, or the bright lozenges of his jester's costume. And what does he learn on his wild journey through man's millennial history? What quintessence will he distill from this accumulation of rubbish and decay, from these half-born or aborted possibilities of form and colour? What symbol will appear as the final cause and meaning of all this. In view of the dazzling versatility of Picasso, one hardly dares to hazard a guess, so for the present I l would rather speak of what I have found in my patients' material.

The Nekyia is no aimless and purely destructive fall into the abyss, but a meaningful katabasis eis antron, a descent into the cave of initiation and secret knowledge. The journey through the psychic history of mankind has as its object the restoration of the whole man, by awakening the memories in the blood. The descent to the Mothers enabled Faust to raise up the sinfully whole human being - Paris united with Helen - that homo totus who was forgotten when contemporary man lost himself to one-sidedness.

ORAN AND THE GIANTESS

You found her sleeping in that cave

Which fonts the western sea, below

All depths I dream. Kissed her gently

As a shade and watched her stir and

Sigh and slowly open her deep

Eyes. She whispered your name as you

Climbed in next to her, singing

All the while. What happened next you

Would not say, except to smile that

Dolphins and sea horses pranced round

The bed while sea-blooms widened to

Hurl wavelike a wild blue perfume.

You drank in draughts the distillate

Of her salt souterrain, till dawn

Awoke me startled here, blank page

Beneath, and pen like her in hand.

My joy’s your shore, this crashing land.

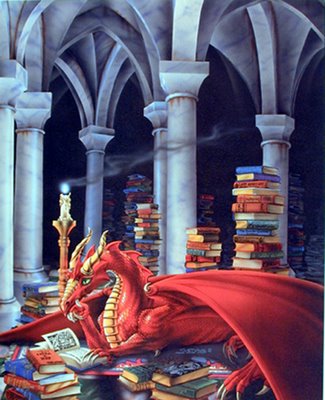

THREE: ENTER THE DRAGON

When the dragon awoke, trouble flared again.

He rippled down the rock, writhing with anger

when he saw the footprints of the prowler who had stolen

too close to his dreaming head.

So may a man not marked by fate

easily escape exile and woe

by the grace of God.

The hoard-guardian

scorched the ground as he scoured and hunted

for the trespasser who had troubled his sleep.

Hot and savage, he kept circling and circling

the outside of the mound. No man appeared

in that desert waste, but he worked himself up

by imagining battle; then back in he’d go

in search of th cup, only to discover

signs that someone had stumbled upon

the golden treasures. So the guardian of the mound,

the hoard-watcher, waited for the gloaming

with fierce impatience; his pent-up fury

at the loss of the vessel made him long to hit back

and lash out in flames. Then, to his delight,

the day waned and he could wait no longer

behind the wall, but hurtled forth

in a fiery blaze. The first to suffer

were the people on the land, but before long

it was their treasure-giver who would come to grief.

The dragon began to belch out flames

and burn bright homesteads; there was a hot glow

that scared everyone, for the vile sky-winger

would leave nothing alive in his wake.

Everywhere the havoc he wrought was in evidence.

Far and near, the Geat nation

bore the brunt of his brutal assaults

and virulent hate. Then back to the hoard

he would dart before daybreak, to hide in his den.

He had winged the land, swathed it in flames,

in fire and burning, and now he felt secure

in the vaults of his barrow; but his trust was unavailing.

-- Beowulf 2287-2323, transl. Heaney

***

Heaney writes in an introduction to his translation,

... the dragon has a wonderful inevitability about him and a unique glamour. It is not that the other monsters are lacking in presence and aura; it is more that they remain, for all their power to terrorize, creatures of the physical world. Grendel comes alive in the reader’s imagination as a kind of dog-breath in the dark, a fear of collision with some hard-boned and immensely strong android frame, a mixture of Caliban and hoplite. And wile his mother too has a definite brute-bearing about her, a creature of slouch and lunge on land if seal-swift in the water, she nevertheless retains a certain non-strangeness. As antagonists of a hero being tested, Grendel and his mother possess an appropriate head-on strength. The poet may need them as figures who do the devil’s work, but the poem needs them more as figures who call up and show off Beowulf’s physical might and his superb gifts as a warrior. They are the right enemies for the young glory-hunter, instigators of the formal boast, worthy trophies to be carried back from the grim testing-ground -- Grendel’s arm is ripped off and mailed up, his head severed and paraded in Heorot. It is all consonant with the surge of youth and the dire compulsion to win fame “as wide as the wind’s home/as the sea around cliffs,” utterly as manifestations of the Germanic heroic code.

Enter then, fifty years later, the dragon. From his dry -stone vault from a nest where he is heaped in coils around the body-heated gold. Once he is wakened, there is something glorious in the way he manifests himself, a Fourth of July effulgence fire-working its path across the night sky; and yet, because of the centuries he has spent dormant in the tumulus, there is a foundedness as well as a lambency about him. He is at once a stratum of the earth and a streamer in the air, no painted dragon but a figure of real oneiric power, one that can easily survive the prejudice which arises at the very mention of the word “dragon.” (xvii-xix)

WYRM

June 18

He’s the old bastard at the

bottom of my brain, coiled

in a vault deeper and older

than the sea, rounding his

thousand drear vertebrae

around a million years of

gold lost down the booty well.

The son was awful, a wreaker

of wrecked halls; the mother

was worse at the bottom

of her mere, defeated only

with a giant’s blade found

hanging on her treasure-wall.

But this guy was the worst

in England’s oldest written

tale, a berserker of wing

and soil awakened from

long stupor to raven

sky and land with pre-mother

pagan fire, the genius

of the tomb that wombs

all later mater father-hater

ire. Here’s the rouge

spermatazoon who cracked

the cosmic egg, bellowing

in sky thunder while

the earth squirmed in

receipt, the oceans

parted like thighs as the

lightning pealed and rang

the bells of hell

all the way from heaven

in addered spits of foam.

Here’s drunk daddy

Saturn eating all his

chillen as they birthed,

the boggler who stained

his chops with every

demiurge to quim the

roiled brain. Here’s the worm

of Uffington who meanders

every night the sky,

feeding his wings on

moon star milk,

ferrying wyrd lucence

back down into his lair

beneath the mountain

under the sea which

lies undermost my

dimmest memories

where all the fathers go

when their persons

have been laid to rest

& battened through

the guts of worms

and shat in dirt as

dusts. It all rains

down that far in a

a ghastly spiculate,

drip by drip of

blood, like shots of

booze upon the tongue

of sleeping beast.

Our final receipt

thus feeds the wyrm

who’s always got one eye

open, no matter how

deep we sleep. Oh

he’s something,

that dragon father

in his lair, brute

and horrid as first

things go. Who am

I to creep down there

and pry this cup

from his coils, so

gold and weirdly

carved with the

world’s seven days?

He only seems to be

sleeping, you know: it’s

more like senescence,

an old man’s swoon where

his thoughts loose in

a river where nothing

quite takes hold

nor ever can let go.

I sing him here

this far down,

singing low as I can

for fear of waking

what will never stop

enraging this sweet land

with that old violence

that dark time’s

secret wand.

THE LAMBTON WORM

Like the monster whom Andromeda was to be sacrificed, the Lambton Worm was the punishment of impiety. The young Heir of Lambton was a wild lad, and one Sunday morning, when everyone else was going to church, he insisted on sitting fishing in the river, in full sight of the worshippers. When the bell had stopped and the church door was closed, the Heir had a catch. A stranger was passing that way, and the Heir called to him to come and look at it. “He’s shaped like an eft,” he said, “and it has seven holes in its head like a lamprey. What is it?”

“I never saw its like,” said the stranger. “It seems to me to bode no good.” The Heir took the thing off the hook, and threw it in disgust into the Castle Well. He thought no more of it for a long time.

But years passed, and the thing grew. The Heir steadied down, and went off to the Holy Land. But while he was away the thing grew too big for the well, and came out and began to ravage the countryside.

At length it got so big that it coiled three times around Lambton Hill, and every night it had to be given the milk of seven cows to keep it quiet. Many people tried to destroy it, but its breath was venemous, its hide was thick and when it was cut to pieces they joined up again.

At last the Heir came back, and by the advice of a wise man he destroyed the creature, wearing spiked aromour so that it wounded itself when it bit him, standing in the rushing waters of the Weare, so that the dragon’s limbs were carried down one by one as he cut them off, and could not re-unite.

But he had to pay for his success by killing the first creature that met him on his return. He failed in this condition, and since then no heir of Lambton has died in his bed.

-- W. Henderson, Notes on the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England, 1879, in Katherine Briggs, The Fairies in Tradition in Literature

Briggs comments: “The dragon which joins itself when it is cut and which coils round hill belongs to an old tradition. We are within hearing of primitive things.”

ENTER THE DRAGON

2004

The Dark -- felt beautiful.

-- Emily Dickinson (Fr. 627)

Beware the scented bed of

Love: it rides upon the

dragon’s back who swims

abyssal realms. Drowse

there and you’ll wake

a molted man of fire,

enrapt inside the rupture

of the devil of deep

welcome. Your wings

will lift you into nights

the size of titan ire,

your eyes whet and keen

for any trace of blue

embroilment to fall,

silklike, from yet

knowable breasts

ripe and leaking

dragon’s milk, booze

poured from paps

of doom. Ride such

nights at your peril,

son of ancient smiles:

Do not presume you

have tooth or troth

sufficient for that dark

demanding angel ride

into the chasm which

splits the fundaments.

Just hold on for your

immortal soul

and let heavens collide

and smash down

every shore. Let every

numen reveal the bestial

depths below, like buoys

singing on blackened tides,

rippled by deep waves

fanning deeper lands

than undreamt Love can go.

RED DRAGON

2005

Lucifer (“Fire-bearer”) in Hebrew is

Helel ben Sahar, “Bright Son of the

Morning.” Later tradition has linked him

to the planet Venus and, somewhat

ambiguously, to other fiery falling

figures: Hephaestus, Prometheus, Phaeton,

Icarus. The pride that made him sit

“in the seat of God” led to his fall; this

is the Greek hubris so often punished

by cosmic justice. The final battle of

Revelation was also interpreted as a

primal battle, the war in Heaven between

Lucifer's forces and those of St. Michael

at the beginning of time. After the fall,

Lucifer, identified with the red dragon,

becomes as hideous a he had become

beautiful -- and changed his name to

Satan.

-- Alice K. Turner, A History of Hell

Oh you should have seen me back then

as I ravened starry heavens in

my silver Rolls convertible, my black

hair like a mane wild in courses of the

night, my hands more perfect than

poured marble at the wheel. There wasn’t

an angelette in all eternity who could

resist my warm smile and icy eyes;

I could plunge a phallus of pure blue fire

right through ‘em with a glance. All those

downy wings spread wide in hot delight

of me! The O-mouths of ecstasy like

black holes birthing a legion suns with

each new name of God they called me

as I plunged and pumped the rebel fire.

I nailed ‘em all in the aeons of my youth,

each a campaign to mount the Master’s throne.

So many followed after me like whorls

of musky afterburn, cupping starlight

from the pools of sweat I left behind

between their ravished breasts, that cold

fire small comfort for eternity yet

infinitely far too much for life The rosewood

inlay above the backseat of that beastly Rolls

toward my end was notched ten billion

times, each scar and angel star, the

only true map of the horny heavens.

That fabled car is now smashed into the rocks

at the bottom of an abyss of black fire.

That’s where me and my element and

vampiric brood were hurled to when the Master

decreed I’d hurled rebellious oats around

the gables of his mansions long enough.

Every way I once shone bright is now

a hellish underglow; the smile I once

reaped angels with in a flash is now

this dragon’s snarl. I once was Lucifer

but that was long ago, before every thrill

heisted from the Master’s lap returned

to me, crying, Satan. Every delight I halved

from His light is now a scale heaped on my flesh,

a coil which circles now the undersides of the

earth’s own mortal plunge to smoking ruin.

But don’t be scared, my friend: I don’t

reveal the visage of desire’s fate till long

after you have fallen through the last bed

of your ding dong dorking life. By day you

only see this middle-aging man who shows

not an inkling of his former years. Who would

guess that the bland man driving in traffic

next to you was once the rapture of an angel’s

crease, the feral pillage of gossamer skirts

in the back seat of a hot car at the darkest

edge of town? No one: that’s the Master’s

curse, to burn the wings off every ache to

romp and roger His high heaven. That outer

fire burned wholly down and in, hurling

in its fumes that tell-all-book of big-night

drives to a place where none will ever

read it. My hell’s found in what burned from

my smile when the tide turned the other

way: when she at last refused to get in

and walked demurely off, leaving me with

this endless ache which no thrust skyward

could ever again slake. Forever now I am

the road not taken by every good impulse,

the shadow of infernal lust which no longer

must compulse maturing virgins of the heart

toward bad and worser ends. The hood

ornament of my Rolls was once the ikon

of my war with God is now all that remains

of my desire, washed on some faraway beach:

I am he who all put behind to start their

histories, the forever middle-aging man

between God and His procreative mysteries.

<< Home