Glaucus' Cloak, My Blue, Blue Book of Seas

Into the full frontal nudity of summer, humid and blowsy, an exult of sensual billows sexually scented and curved but deeper, wilder, everywhere at once ... I sing here of that sot, seated here at my usual dim hour with the night heaving in the window and a distant sea insatiable, sighing and heaving and smashing and ebbing something inside my voice, as if I were borne on waves long ago to a salt sotto voce, the lover born of love rebirthing in each daily verbal baptism, these jaunts on plural blue ... you figure it out, if you care to dare ...

***

ULYSSES AND THE SIREN

Samuel Daniel (1562-1619)

Come worthy Greeke, Vlisses come

Possesse these shores with me;

The windes and seas are troublesome,

And here we may be free.

Here may we sit, and view their toile

That travaile in the deepe

And ioy the day in mirth the while,

And spend the night in sleepe.

***

According to “The Voyage of St. Brendan,” Brendan burned a book containing stories about the wonders of God’s creation out of disbelief. For this reason he is sent on a voyage so as to see with his own eyes certain divine manifestations which earlier he had refused to credit. In this way he is to recover the book by refilling it with the wonders which he witnesses on his voyage. The majority of the phenomena which he comes across are related to man’s actions and behaviour in this life and the circumstances consequent upon them in the Afterlife. Brendan encounters souls in hell, heaven and paradise. The astonishing and sometimes frightening experiences restore his belief.

— Clara Strijbosch, “The Heathen Giant in the Voyage of St. Brendan”

(School of Celtic Studies DIAS 1999, p. 369)

***

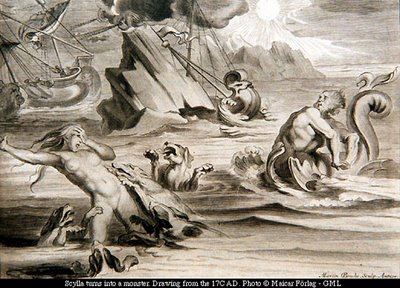

GLAUCUS AND SCYLLA

-- from Bullfinch's The Age of Fable

One day Glaucus saw the beautiful maiden Scylla, the favourite of the water-nymphs, rambling on the shore, and when she had found a sheltered nook, laving her limbs in the clear water. He fell in love with her, and showing himself on the surface, spoke to her, saying such things as he thought most likely to win her to stay; for she turned to run immediately on the sight of him, and ran till she had gained a cliff overlooking the sea.

Here she stopped and turned round to see whether it was a god or a sea animal, and observed with wonder his shape and colour. Glaucus partly emerging from the water, and supporting himself against a rock, said, "Maiden, I am no monster, nor a sea animal, but a god: and neither Proteus nor Triton ranks higher than I. Once I was a mortal, and followed the sea for a living; but now I belong wholly to it."

Then he told the story of his metamorphosis, and how he had been promoted to his present dignity, and added, "But what avails all this if it fails to move your heart?" He was going on in this strain, but Scylla turned and hastened away. Glaucus was in despair, but it occurred to him to consult the enchantress Circe. Accordingly he repaired to her island -- the same where afterwards Ulysses landed ... After mutual salutations, he said, "Goddess, I entreat your pity; you alone can relieve the pain I suffer. The power of herbs I know as well as any one, for it is to them I owe my change of form. I love Scylla. I am ashamed to tell you how I have sued and promised to her, and how scornfully she has treated me. I beseech you to use your incantations, or potent herbs, if they are more prevailing, not to cure me of my love,-- for that I do not wish,-- but to make her share it and yield me a like return."

To which Circe replied, for she was not insensible to the attractions of the sea-green deity, "You had better pursue a willing object; you are worthy to be sought, instead of having to seek in vain. Be not diffident, know your own worth. I protest to you that even I, goddess though I be, and learned in the virtues of plants and spells, should not know how to refuse you. If she scorns you scorn her; meet one who is ready to meet you half way, and thus make a due return to both at once."

To these words Glaucus replied, "Sooner shall trees grow at the bottom of the ocean, and sea-weed on the top of the mountains, than I will cease to love Scylla, and her alone." The goddess was indignant, but she could not punish him, neither did she wish to do so, for she liked him too well; so she turned all her wrath against her rival, poor Scylla. She took plants of poisonous powers and mixed them together, with incantations and charms. Then she passed through the crowd of gambolling beasts, the victims of her art, and proceeded to the coast of Sicily, where Scylla lived.

There was a little bay on the shore to which Scylla used to resort, in the heat of the day, to breathe the air of the sea, and to bathe in its waters. Here the goddess poured her poisonous mixture, and muttered over it incantations of mighty power. Scylla came as usual and plunged into the water up to her waist. What was her horror to perceive a brood of serpents and barking monsters surrounding her! At first she could not imagine they were a part of herself, and tried to run from them, and to drive them away; but as she ran she carried them with her, and when she tried to touch her limbs, she found her hands touch only the yawning jaws of monsters. Scylla remained rooted to the spot. Her temper grew as ugly as her form, and she took pleasure in devouring hapless mariners who came within her grasp. Thus she destroyed six of the companions of Ulysses, and tried to wreck the ships of AEneas, till at last she was turned into a rock, and as such still continues to be a terror to mariners. Glaucus, alas, never stopped loving the she-beast.

The existence of an abundant deep-sea fauna was discovered, probably millions of years ago, by certain whales, and also, it now appears, by seals. The ancestors of all whales, we know by fossil remains, were land mammals. They must have been predatory beasts, if we are to judge by their powerful jaws and teeth. Perhaps in their foragings about the deltas of great rivers and around the edges of shallow seas, they discovered the abundance of fish and other marine life and over the centuries formed the habit of following them farther and farther into the sea. Little by little their bodies took on a form more suitable for aquatic life; their hind limbs were reduced to rudiments, which may be discovered in the modern whale by dissection, and the forelimbs were modified into organs for steering and balancing.

-- Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us

***

When they drew nigh to the nearest island, the boat stopped ere they reached a landing--place; and the saint ordered the brethren to get out into the sea, and make the vessel fast, stem and stern, until they came to some harbour; there was no grass on the island, very little wood, and no sand on the shore. While the brethren spent the night in prayer outside the vessel, the saint remained in it, for he knew well what manner of island was this; but he wished not to tell the brethren, lest they might be too much afraid. When morning dawned, he bade the priests to celebrate Mass, and after they had done so, and he himself had said Mass in the boat, the brethren took out some un-cooked meat and fish they had brought from the other island, and put a cauldron on a fire to cook them, After they had placed more fuel on the fire, and the cauldron began to boil, the island moved about like a wave; whereupon they all rushed towards the boat, and im-plored the protection of their father, who, taking each one by the hand, drew them all into the vessel; then relinquishing what they had removed to the island, they cast their boat loose, to sail away, when the island at once sunk into the ocean.

Afterwards they could see the fire they had kindled still burning more than two miles off, and then Brendan explained the occurrence: ‘Brethren, you wonder at what has happened to this island,’ ‘Yes, father,’ said they: ‘we wondered, and were seized with a great fear.’ ‘Fear not, my children,’ said the saint, ‘for God has last night revealed to me the mystery of all this; it was not an island you were upon, but a fish, the largest of all that swim in the ocean, which is ever trying to make its head and tail meet, but cannot succeed, because of its great length. Its name is Jasconius.’

-- Vita Brendani (“The Voyage of St. Brendan”)

IMMRAMA

Immrama,, medieval Latin,

“wandering about”

St. Brendan’s voyage

made the sea for him

a breviary of depths

and island wonders

unbound by heaven’s

blue. In the arrogance of

youth he had burned

a book of wonders

decrying all wet

sooth as false;

in punishment a blue

God shipped his bones

offshore to immrama

through every salt

chapter of His book,

shoring every

strange and wild receipt

which no one can name

nor return from ever

sold or sane again.

That voyage made

Brendan’s heart

a sainted keel

and then a whale, a

log which wrote itself

so long on water

that its pages paled to

blue, its language

scrawled in finny

majescule. Each time

I write sea songs

the sound of Brendan’s

surf grows deeper,

a Triton's organum

of wet collapsing

thunder arising from

the darkest angels’ throat

to fall two thirds

the way to hell.

I’ve been writing

his book of sea-ward

thrall so long

a salt-tang malts

my every rhyme and

meter, diving me

ever deeper. There

are down there

nymphs whose

sex is too blue

for mortal peckers,

though I slide

this next song

deep and slow

in the sweetest

shudder of that

slick black sin.

The work completes

the maker in its

forge of verbal froth,

hurling forth the

wave-borne rider

on the first and ever

trope to wash

the shore, ever

deeper down

the blue ladder of

besotted salt

domains, my mouth

that clarion bell

which klaxons

a sweet and stark

abysm more naked

and divine than birth

itself. So bring on

the next isle, old

master, fill it with

strange and stranger

isms of soul fish;

and I will rollick

in that sound

and write that

blue baud down,

past my hips, past

my knees, past my

ankles to the lees

of those first huge

waves to wash

my heart,

anointing the

singer sailor and

lover to start

that first saint’s

work all over again.

***

... No,

In all the argosy of your bright hair I dreamed

Nothing so flagless as this piracy.

But now

Draw in your head, alone and too tall here.

Your eyes already in the slant of drifting foam;

Your breath sealed by the ghosts I do not know.

Draw in your head and sleep the long way home.

- Hart Crane, "Voyages IV"

***

Each girl rose from her chair and walked through her own rising echo into someone else’s, until they all overlapped and I couldn’t tell who might be chosen and who would not. The echo of a laughing eye lightly touched mine on its way up and down my body; long white curtains streamed out an enormous window on an ancient city; a demon whispered to a clitoris as if it were an ear; a girl laughed and ate cherries from a plastic bowl; I pounded a door closed to me forever. These and thousands of other bright-pointed moments became tiny and featureless as grains of sand among grains, condemned to whirl forever.

-- Mary Gaitskill, Veronicca

***

In his novel The Island of the Day Before (transl. to the English 1995) Umberto Eco tells the story of Roberto Della Griva, an Italian noblemen whose ship wrecks in 1643 in the Southern Pacific and floats on a piece of wood to a deserted ship which lies offshore an island -- effectively shipwrecking him on a ship. Eco’s description of the shipwreck is harrowing and precise for every shipwrecked suffered in the imagination:

“From a breach in the flank Roberto sees, or dreams he is seeing, cyclades of accumulated shadow and thunderbolts dart and roam over the fields of waves; and to me this seems excessive indulgence for a taste for precious quotation. But in any event, the Amaryllis tilts in the direction of the castaway ready to be cast away, and Roberto on his plank slides into an abyss above which he glimpses, as he sinks, the ocean freely rising to imitate cliffs; in the delirium of his eyelids he sees fallen Pyramids rise, he finds himself an aquatic comet fleeing along the orbit of that turmoil of liquid skies. As every wave flashes with lucid inconstancy, here foam bends, there a vortex gurgles and a fount opens. Bundles of crazed meteors offer the counter-subject to the seditious aria shattered by thundering; the sky is an alternation of remote lights and downpours of darkness; and Roberto writes that he saw foaming Alps within wanton troughs whose spume was transformed into harvests; and Ceres blossomed amid sapphire glints, and at intervals in a cascade of roaring opals, as if her telluric daughter Persephone had taken command, exiling her plenteous mother.

“And, among errant, bellowing beasts, as the silvery salts boil in stormy tumult, Roberto suddenly ceases to admire the spectacle, and becomes its insensate participant, he lies stunned and knows no more of what happens to him. It is only later that he will assume, in dreams, that the plan, by some merciful decree of heaven or through the instinct of a natant object, joins in that gigue and, as it descended, naturally rises, calmed in a slow saraband -- then in the choler of the elements the rules of every urbane order of dance are subverted -- and with ever more elaborate periphrases it moves away from the heart of the joust, where a versipellous top spun in the hands of the sons of Aeolus, the hapless Amaryllis sinks.”

In Keats’ handling of the tale, Endymion, the eternally thirsting youth of song, travels through the underworld in his quest, coming upon Glaucus, old man of the sea, doomed to a thousand years of senility for having outraged Circe in his love for Scylla. This is how Endymion comes upon that ancient augur of the sea:

***

He saw far in the concave green of the sea

An old man sitting calm and peacefully.

Upon a weeded rock this old man sat,

And his white hair was awful, and a mat

Of weeds were cold beneath his cold thin feet;

And, ample as the largest winding-sheet,

A cloak of blue wrapped up his aged bones,

O’erwrought with symbols by the deepest groans

Of ambitious magic: every ocean-form

Was woven in with black distinctness; storm,

And calm, and whispering, and hideous roar,

Quicksand, and whirlpool, and deserted shore

Were emblemed in the woof; with every shape

That skims, or dives, or sleeps, ‘twixt cape and cape.

The gulfing whale was like a dot in the spell.

Yet look upon it, and ‘twould size and swell

To its huge self, and the minutest fish

Would pass the very hardest gazer’s wish,

And show his little eye’s anatomy.

Then there was pictured the regality

Of Neptune, and the sea nymphs round his state,

In beauteous vassalage, look up and wait.

Beside this old man lay a pearly wand,

And in his lap a book, the which he conned

So steadfastly, that the new denizen

Had time to keep him in amazed ken,

To mark these shadowings, and stand in awe.

-- Endymion III.189-217

***

Keats began his first major poem Endymion by travelling to the Isle of Wight. After reading the phrase, “Do you not hear the sea?” in King Lear, he writes the shorter poem “On The Sea.” According to Jackson Bate in his biography of Keats, “The suggestions of promise, vastness, uncertainties again catch at him -- The ‘eternal whisperings,’ the mighty swell that glutes ‘ten thousand caverns,’ the thought of the wideness of the sea.”

“DO YOU NOT HEAR THE SEA?”

-- King Lear

June 3

Yes, your waters lap this far,

salt regnum, at this margin

which resembles no bright shore

I thought I’d find her on

foolishly believing that

waves of reallest water were

the surest prayer of all:

You are here, at this 4 a.m.

on Sunday morning in the

depths of this next summer,

lapping through the garden

half the blackest whiskey brine

to limn my worst memories

and half of that collapsing foam

which spanks the sun afresh

and sets a stallion wild across

the steppes of the next raging

summer’s day. You fold and

crash Your distant scree

in almost-audibles meshed

just past my window screen,

inside the plush weave of

swoooning crickets, their

sighing siesta of sexual sleep

immensely Yours, tiding in my ear

a lover’s softest cries, wetly

collapsing under the hardest

freight I’ve hurled between

loves’s knees. These words

gout in Your warm sea

like sperm of great antiquity,

a spasm cloud of sea-horse spawn

delved from Arion’s mount

as he sang his shipwrecked heart

to shore. Oh I hear You all right,

old man dreaming deep

beneath the concave sea;

Your shores are biblical enough

to swoon the fey libidos

of ten thousand naiad quim,

their nascence hot in my

verbatim scrawl, their absence

all you brood in the cold

conch-chambers of my dream.

My book is in Your hands;

I’m only writing what I saw

when I slipped her panties down,

her nakedness on pale moonlit

sheets bound in Your breviary.

The watery expanses I dived

there split and spilt my binding

on its spine of certain round

in a slow,glissading sound.

In a way, I have choired so long

Your quintessential text

that I have claimed Your throne

right here, sitting on this white

writing chair at the bottom of

the night so many miles from

actual shores of actually wild seas.

Like Glaucus I am cursed

to eternally rehearse the

propoundings of a sea

where there is none and less

to see of it that it sounds

more real and true, soaking an

ever deeper voice beneath

the silent, dark-hearsed sea.

My book is drowned in he

who shipwrecked long ago

a love too wild, too wide for water

and was condemned for

a thousand years to a

goaty dry senility

when only pages were permitted

to receive the vaster

crashings of the sea,

rescuing the paired numens

love throws like chum to night

by writing their raptures down.

Some day a youth will come

who knows the last line of the tune

and I, like You, will wake,

and like Yours, my love will too

revive on her drifting departing

bed. And the two of us

will come home to this shore

and make of it a home

enthroned on sheets as pure as sand,

as secure as that far sound

that washes me from page to

page in one long farewelling poem

about the soundings of a sea

I cannot hear but do.

***

Glaucus, condemned to a thousand years of senility by Circe, lives out his sentence. He sees a shipwreck, and though he vainlly attempts to rescue the victims, his effort is rewarded. He learns from a scroll in the hand of one of the victims that if he tries to recover all the bodies of lovers drowned at sea, a youth will eventually appear who can help him and also be the means of his deliverance. Endymion turns out to be the long-awaited youth. They must perform certain rites, which they do; the scroll is torn, and the pieces, now invested with magic, bring life and youth at the touch. Glaucus loses his senility; Scilla is revived; one by one the dead lovers come to life.

***

STRING OF PEARLS

June 4

My love and choiring song

of it are united by the sea

along a string of pearls

hung round its blue neck,

each heavy, swirled,

noctilucent, wild:

I recall them here

as islands of a tale

You wove me through

on waves of heartbreaking

so sexual yet deeper hue:

There’s my mother singing

over me as I played on

the beach near Jacksonville,

eating shovels of sand

to build a castle of that sound

of my mother singing

over the sea -- I was blithe

to the birthmark I displayed,

a heart with an arrow through

it right over my right breast

but surely it was highly

pleased with our sweet

mythologem, and plunged

it deep into my depth:

That’s me at three years

old at Cape Cod when

waves of song rose from

that vault, my mouth

wide as sang loves songs

to Big Toad, my captive

frog, who watched me

from the bottom of

a yellow plastic pail --

jail perhaps for

that amphibian,

but Yale for me,

my college of

water songs as my

little voice sang

all the way from

here to that mashed

pre-literate sea;

There is the girl

I watched on Pillow

TV at five

(face down on

my bed) who walked

around that well

within and fell,

whose body welcomed

mine as I hauled

her up to safety;

There is that

Naiad shape which

invoked those

sand castles

I built on vacations

to Florida throughout

childhood, each a

shining mound of her

cupped in my wet

hands, breasts and

hips and buttock-curves

the waves erased

in a long ebbing hiss;

There is the June morning

when I was baptized

off Melbourne Beach -- I

was thirteen -- The wave

which passed over me

washed me clean

and freed me to fall

down all the way to God;

And there is that

April morning seven

years later when

I dreamt of summer’s ocean

gleaming bright and blue

far offshore, my

limp cock still buried

in my first love’s

cunt as we slept

off our second wild

night -- the peace

I felt was like a clear blue

space, the floating

wash of an infinitely

wild baptism -- Two days

later when I woke

she was forever gone;

There is that morning

at Cocoa Beach four

years later when my

second great love

and I walked out onto the

sand after a a night of

four-condom sex -- she

stood smiling at me in the

surf as the sun rose over

her shoulder, raising love

to some highest altar

from which we fell like stones;

There is that breezy too-

late summer afternoon at

Playalinda beach three years

later when my third love

sucked me off so good --

the choiring mash of waves

greeted the spasm of my

sperm which gouted up

into her greedy mouth

with something if not

quite welcome a booming

receipt, the song’s

rapture now complete --

She smiled with that

foamed-up mouth and

kissed me for the last time,

heading up to Chicago

with her son to live

with a better man;

There is that hotel

at Melbourne Beach

three years later

when first wife and I

tried to make love for

a while, the morning

in the east window

too sacred to be horny,

too riddled with old shots --

brilliant sunshine

over the sea, a choir

of washing waves, yes,

but every fish in the

sea vacated between

us, though we tried

our best;

There is that same

hotel six years later

when my poet-lover and

I went wild for three

nights in crashing June,

exhausting our exult into

each other in the

raptest hours of summer’s

day and night -- Our first

night there a full moon

rose ferally on black water

as I licked and sucked

her lunula (she sprawled

back on the dinette table)

next to the eastern windows

as thunders split the west,

that sound far deeper than

we could ever find words

together, fools though we

were for believing such

pages could exist;

There is the night in

mid-September two years

later when a girl-woman

I would never be permitted

to love drove with me to

Cocoa Beach. We stood

on the pier watching huge

waves approach in greenblack

sets, hurled by a distant

hurricane -- The sight of her

leaning over the rail enrapt at

those moony booming waves

was all that was meant,

her red dress fluttering my

flag of surrender and

defeat which it seems the

ocean always bids me raise;

And there is that winter’s

night at that same hotel

at Melbourne Beach four

months later when it almost

froze outside, when my

future second wife emerged

from the bathroom in a sleek

white Calvin Klein sleep-gown --

she stared at me across the

room with her arms crossed

on her breasts, and whispered

“I’m so scared” -- the purest

invitation to a dance which

ten years later still defines

the wildest raptures of a beach

I’ll always sing and rarely

visit and never truly reach;

You wended all those pearls

on the strand which threads

my heart and voice and song,

blue master, salt queen,

disaster of the real life

and siesta of my dream:

I give it back to You

inside the plush covers of

this box of poems no one

wants to read;

If this is just brined

fridge art for the mother

of the ages, then so be it;

I’ve nothing else for you to

read but this next summer’s

day with my wife sick in

our bed upstairs and the

world ever more frayed and

desperate and weary.

So here’s Your’s; and now

I go to softly stroke my

wife’s soft curves, and say

my prayers to every wave

to wake and wild my verbs.

Indeed -- the verse always finds renewal in the youngest wave, finding in the splash of wet wild blue soak the deepest inkwell of all ...

***

GLAUCUS REVIVED

The old man raised his hoary head and saw

The wildered stranger -- seeing not to see,

His features were so lifeless. Suddenly

He woke as from a trance; his snow-white brows

Went arching up, and like two magic ploughs

Furrowed deep wrinkles in his forehead large,

Which kept as fixedly as rocky marge,

Till round his withered lips had gone a smile.

Then up he rose, like one whose tedious toil

Had watched for years in forlorn hermitage,

Who had not from mid-life to utmost age

Eased in one accent his o’er-burdened soul,

Even to the trees. He rose: he grasped his stole,

With convulsed clenches waving it abroad,

And with a voice of solemn joy, that awed

Echo into oblivion, he said:

“Thou art the man! Now shall I lay my head

In peace upon my watery pillow: now

Sleep will come smoothly to my weary brow.

O Jove! I shall be young again, be young!

O shell-borne Neptune, I am pierced and stung

With new-born life! What shall I do? Where go,

When I have cast this serpent-skin of woe?

I’ll swim to the syrens, and one moment listen

Their melodies, and see their long hair glisten;

Anon upon that giant’s arm I’ll be,

That writes about the roots of Sicily;

To northern seas I’ll in a twinkling sail,

And mount upon the snortings of a whale

To some black cloud; thence down I’ll madly sweep

On forked lightning, to the deepest deep,

Where through some sucking pool I will be hurled

With rapture to the other side of the world!

O, I am full of gladness! Sisters three,

I bow full hearted to your old decree!

Yes, every god be thanked, and power benign,

For I no more shall wither, droop, and pine.

-- Keats Endymion, III.235-54

***

Concluding with this conclusion to the Vita Brendanii:

XXVI

St Brendan afterwards made sail for some time towards the south, in all things giving the glory to God. On the third day a small island appeared at a distance, towards which as the brethren plied their oars briskly, the saint said to them: ‘Do not, brothers, thus exhaust your strength. Seven years will have passed at next Easter, since we left our country, and now on this island you will see a ‘holy hermit, called Paul the Spiritual, who bas dwelt there for sixty years without corp9ral food, and who for twenty years pre-viously received his food from a certain animal.’

When they drew near the shore, they could find no place to land, so steep was the coast; the island’ was small and circular, about a furlong in circumference, and on its summit there was no soil, the rock being quite bare. When they sailed around it, they found a small creek, which scarcely admitted the prow of their boat, and from which the ascent was very difficult. St Brendan told. the brethren to wait there until he returned to them, for they should not enter the island without the leave of the man of God who dwells there. ‘‘When the saint hail ascended to the highest part of the island, he saw, on its eastern side, two caves opening opposite each other, and a small cup-like spring of water gurgling up from the rock, at the mouth of the cave in which the soldier of Christ dwelt. As St Brendan approached the opening of one of the caves, the venerable hermit came forth from the other to meet him, greeting him with the words: ‘Behold how good and how pleasant for brethren to dwell together in unity.’’ And then he directed St Brendan to summon all the brethren from the boat. When they came he gave each of them the kiss of peace, calling him by his proper name, at which they all marvelled much, because of the prophetic spirit thus shown. They also wondered at his dress, for he was covered all over from head to foot with the hair of his body, which was white as snow from old age, and no other garment had he save this.

St Brendan, observing this, was moved to grief, and heaving many sighs, said within himself: ‘Woe is me, a poor sinner, who wear a monk’s habit, and who rule over many monks, when I here see a man of angelic condition, dwelling still in the flesh, yet unmolested by the vices of the flesh.’ On this, the man of God said: ‘Venerable father, what great and wonderful things has God shown to thee, which He has not revealed to our saintly predecessors! and yet, you say in your heart that you are not worthy to wear the habit of a monk; I say to you, that you are greater than any monk, for the monk is fed and clothed by the labour of his own hands, while God has fed and clothed you and all your brethren for seven years in His own mysterious ways; and I, wretch that I am, sit here upon this rock, without any covering, save the hair of my body.’ Then St Brendan asked him about his coming to this island, whence he came, and how long be had led this manner of life. The man of God replied: ., For forty years I lived in the monastery of St Patrick, and had the care of the cemetery. One day when the prior had pointed out to me the place for the burial of a deceased brothel’, there appeared before me an old man, whom I knew not, who said: ‘Do not, brother, make the grave there, for that is the burial-place of another.’ I said’ ‘Who are you, father?’ ‘Do you not know me?’ said he. ‘Am I not your abbot?’ ‘St Patrick is my abbot,’ I said. I am he,’ he said; and yesterday I departed this life and this is my burial-place.’ He then pointed out to me another place, saying: ‘Here you will inter our deceased brother; but tell no one what I have said to you. Go down on to-morrow to the shore, and there you will find a boat that will bear you to that place where you shall await the day of your death.’ Next morning, in obedience to the directions of the abbot, I went to the place appointed, and found what he had promised. I entered the boat, and rowed along for three days and nights, andthen I allowed the boat to drift whither the wind drove it. On the seventh day, this rock appeared, upon which I at once landed, and I pushed off the boat with my foot, that it may return whence it had come, when it cut through the waves in a rapid course to the land it bad left.

‘On the day of my arrival here, about the hour of none, a certain animal, walking on its hind legs, brought to me in its fore paws a fish for my dinner, and a bundle of dry brushwood to make a fire, and having set these before me, went away as it came. I struck fire with a flint and steel, and cooked the fish for my meal; and thus, for thirty years, the same provider brought every third day the same quantity of food, one fish at a time, so that I felt no want of food or of drink either; for, thanks to God, every Sunday there flowed from the rock water enough to slake my thirst and to wash myself.

‘After those thirty years I discovered these two caves and this spring-well, on the waters of which I have lived for sixty years, without any other nourishment whatsoever. For ninety years, therefore, I have dwelt on. this island, subsisting for thirty years of these on fish, and for sixty years on the water of this spring. I had already lived fifty years in my own country, so that all the years of my life are now one hundred and forty; and for what may remain, I have to await here in the flesh the day of my judgment. Proceed now on your voyage, and carry with you water-skins full from this fountain, for you will want it during the forty days’ journey remaining before Easter Saturday. That festival of Easter, and all the Paschal. holidays. you will celebrate where you have celebrated them for the past six years, and after-wards, with a blessing from your procurator, you shall proceed to that land you seek, the most. holy of all lands; and there you will abide for forty days, after which the Lord your God will guide you safely back to the land of your birth.’

XXVII

St Brendan and his brethren, having received the blessing of the man of God, and having given mutually, the kiss of peace in Christ, sailed away towards the south during Lent, and the boat drifted about to and fro, their sustenance all the time being the water brought from the island, with which they refreshed themselves every third day, and were glad, as they felt neither hunger nor thirst. On Holy Saturday they reached the island of their former procurator, who came to meet them at the landing-place, and lifted everyone of them out of the boat in his arms. As soon as the divine offices of the day were duly performed, he set before them a repast.

In the evening they again entered their boat with this man, and they soon discovered, in the usual place, the great whale, upon whose back they proceeded to sing the praises of the Lord all the night, and to say their Masses in the morning. When the Masses had concluded, Jasconius moved away, all of them being still on its back; and the brethren cried aloud to the Lord: ‘Hear us, O Lord, the God of our salvation.’. But St Brendan encouraged them: ‘Why are you alarmed? Fear not, for no evil shall befall us, as we have here only a helper on our journey.’

The great whale swam in a direct course towards the shore of the Paradise of Birds, where it landed them all unharmed.

<< Home