Pains

Music is a feeling, then, not sound;

And thus it is what I feel,

Here in this room, desiring you,

Thinking of your blue-shadowed silk,

Is music,

-- Wallace Stevens, “Peter Quince at the Clavier”

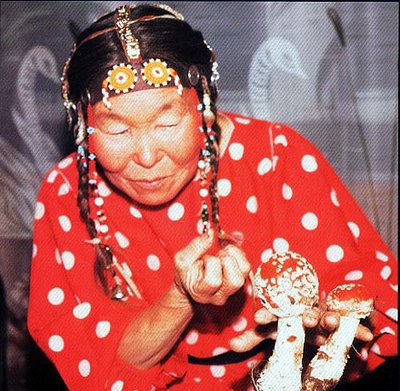

There are also the “pains,” which are thought of both as sources of power and causes of illness. These “pains” appear to be animated and sometimes even have a certain personality. They do not have human forms, but they are thought of as concrete. Among the Hupa, for example, there are “pains” of every color; one is like a piece of raw flesh, others resemble crabs, small deer, arrowheads, and so on. Belief in “pains” is general among the tribes of Northern California, but is rare or unknown in other parts of North America.

The damagoni of the Achomawi are at once guardian spirits and “pains.” A shamaness, Old Dixie, relates how she received the call. She was already married, when, one day, “my first damagoni came to find me. I still have it. It is a little black thing, you can hardly see it. When it came the first time it made a great noise. It was at night. It told me that I must go see it in the mountains. So I went. I was very frightened. I hardly dared go. Later I had others. I caught them. They were damagoni that had belonged to other shamans and that had been sent to poison people on other shamanic errands.” Old Dixie sent out one of her own damagoni and caught them. In this way she had come to have over fifty damagoni, whereas a young shaman has only three or four. The shamans feed them on the blood that they suck during their cures. According to Jaime de Angulo these damagoni are at once real (bone and flesh) and fantasies. When the shaman wants to poison someone he sends a damagoni. “Go find So-and-so. Enter him. Make him sick. Don’t kill him at once. Make him die in a month.”

-- Mercea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy

DUOTONE

Feb. 11, 2006

If you’re going to write this properly

you’d better be prepared to sing it

both ways, as tone and archetypal

drone, as music cauled in conceit.

Call it a duotone of thought and heart,

black inkings of a blue’s deep skein.

A poem is thus pain and cure,

a wound’s own physic retelling

the up- and downsides of life’s

onswelling surf, where loves

and losses join in matrimony

to the strange interior lands

they took you to while you sat

imprisoned in the very self

which ligaments inside to out

as I to Thou. Here memory

finds flesh again the way first light

warmed her hair three decades ago,

so sure as delvings of creation’s

fire that my hand is stabled to

trace her properly all over again

both there in spring’s first exult

and roaming the dark cold

garden outside as I sit

here in a much later,

no less enraptured chair.

Something leapt across the gap

on those glowing strands of hair

scattered wantonly on my thin

pillow, the orchid bounty of

a belling thrall, sadly bellied by the

steely undertow of a fate,

pains I’ll never fully recover from

having altared them so high with

every blue abysm to surge the

siegings of my blood’s receipt of air.

The poem is the eventual name

for that bridge and the shores

it joined at last which bears a

blue infernal traffic in the ballsy

Gaelic brogue of an intercourse

no love can fully scree, much

less domain. Love is just the half

of it, the visible ventricles of

a heart which is much wilder

and dark-lucent and incessant

in its weave inside beneath my

swimming tongue. Sundered psalmist,

defiant weaver of white flags,

marauder whose tines I winnow

like an ancient pilot fish,

this song is betweening’s master,

ever both world and words for it,

never resting, never sated, always

cresting fresh-salted by old

wounds’ superations keeping noun

and verb at odds, ever praising

the difference in which I and Thou

become the fascia of a delight

which never quits or quells or

quakelike thunders and comes hard.

THIS IS MY BOX

Feb. 12, 2006

I loved Menotti’s “Amahl

and The Night Visitors”

when I was a kid, faux-

directing the Pittsburgh

Symphony on TV when I

was three, lounging by

the stereo in my father’s

study when I was ten or

so, reveling in the aching

pathos of a poor shepherd

boy’s night, lamed, fatherless,

tending his meager flock

in wide desert scrabble

as eternal as the desertions

that can kill a heart.

Amahl’s boy fusion of loss and

yearning was surely mine,

starry and cold and powerfully

linked to the infant mewling

in a nearby manger —a

feeling blent of grief and

beauty which was somehow

stronger than all

of the shadows in his house

and mine, millennia away

in fat Evanston where our

family got thoroughly mauled

by each other and God and sex

and The Sixties. I especially

loved that song by Caspar

the silly third wise man—almost

a Stooge—about the box he’d

carried all his years and which

he would offer the child,

a box filled with everything startling

and wonderful in the world.

“This is my box, this is my box,

I never travel without my box,”

Caspar sang, each verse

opening drawers laden with

strangeness and pleasure, lapis

lazuli eggs and dinosaur tears

encased in amber, fragrant dried

flowers and enormous shark

teeth, rude stone goddesses and

jewelled tweezers for plucking

the burning plumage of gold geese

What a collection! I always wanted

a box like that, some treasure

chest of oddities and ardors and

devices not vaulted anywhere

else in the world, at least

not in that peculiar way I

most desired, whatever that

was. That ache was probably

why I was so fascinated with

the devious cigarette lighter

used by the spy hero in “In

Like Flint,” which had,

according to James Coburn,

“87 different uses—

88, if you need a light.”

One day I tried to reverse-

engineer that contraption

on paper, drawing 87 rectangles

in a big rectangle and then

trying to name each one.

What an exercise

in desire’s floral consummations,

impossible and permanently

inked! I believed back then

that plural uses were

necessary if you planned

to win in the world; a hero

required all the mojos he

could muster if he was

to beat his evil adversary,

blowing up the monster’s

island laboratory with

all his goons; surely

the 47th or 59th use

of that Zippo was exactly

how the hero could

escape such devastation

with such harrowing

hair’s-breadth (cunt-hair?)

precision, leaping over

the falls with 5 half-naked

girls in bobbing drums.

Savagery, cunning,

balls, and ire: to light

the fire you need a Flint

and I sure wanted to

be one, paused, flicking

the wheel to say

“88, if you need a light.”

Now I read how shamans

collected damagoni in their

rucksack of ills ‘n’ cures,

each both guardian spirit

and sheer pain, a singular

employ in the choir with

with a two-faced purpose,

as to cure a cold and freeze an

enemy’s pent smile.

A shamaness named Old Dixie

said she had over 50 damagoni

in her truck, queening over

all the young buck magicos

who could only muster

two or three salvos with

their tongues. All that makes

me wonder just what

verbal sprites are cabinned

here inside this trusty

somewhat rusty steamer

of steely verse, yowling and

harrumphing in the engine

room’s hellish mash of

gleaming oiled gears, keeping

these songs chugging along

through a sea of dark mornings,

There’s Oran down his well

decanting old sea gods,

and Roethke sweeting his field

of brually-blowing wheat.

There's Cupid on his high

hard horse cuckolding waves

of their siphoning wives,

there’s Shakespeare booming

through to galaxies beyond

the words we thought

we knew. Some redheaded

siren is raking blue waters

with the nails of her song,

urging every salmon of

fire to leap to the lees

of her hips; and further

out you’ll find the leaky nips

of a dark blue madonna

who delves my every

ejaculation with ululations

of pale shores; and there

in the rip current rides

the hard-galloping gent

whose blue eyes are pure

ice glinting not of any

light borne of days but

belongs to God’s spectra anyway,

far right of violet perhaps

or under the cleft in

Persephone’s red fruit, lending

a cold metallish sound

to these worked-up hooves.

All of those numens -- call ‘em

sprites or jinns or dervish

whirls of verbal moods ---

all of them jackal and jest

the days wash these lines,

vaulted somewhere under

my tongue behind my ear

and under my balls in

the darker vaults of my heart,

the greater half of a heat

which names all it believes

but remains itself unseen,

unridden, urn-bidden to lean

daft against the wind.

This is my box, my

hurlyburly juke of songs,

ferried from a hundred

distant shores:

It is my gift to you,

my unsaved Beloved, my

unsounded depth, my

unslakable destination

for which my soles will

never quite shore. Now

you’ve heard of all

I keep in the first drawer:

you will surely dream

what’s kept in the second.

But what is in the

third drawer I sing?

Here I keep the depths

of my world, the heart

of that lonely shepherd

boy who raptured mine

playing in in a minor key

of major third harmony

on his desert flute,

lit by that perfect

abandoned night where I walk

walk without meters

or crutch, where I store

the most sacred blunts

of all— “Licorice!” the

third wise man sang

and here I refrain,

Black sweet licorish

Black sweet licorish

— Have some!

<< Home