Learning To Write

Avoid what tempts,

move toward what threatens..

-- L.S. Asekoff

Jack London believed that a writer needed three things in order to write: technique, experience and a philosophy. That’s a good way to describe how I finally got around to writing. For me, learning to write meant first becoming an apprentice to words, then soaking those words in the darkness of the world, and finally distilling them into a truth or two. The result, I found, was a beginning.

* * *

Until April 1978, I’d been a committed student, dedicated to a fault to my courses at a small college in Washington state. For two and a half years, nothing else mattered. I walked alone, sometimes content with that uninterrupted solitude, at other times banging on inner walls. But I kept studying.

I wanted to become a poet. Professors had been encouraging. I had a way with words, a knack for the nice phrase, an eye for description. However, I found myself blocked. I thought I had little to write about. I saw nothing noteworthy in my daily routines. I also feared the darkness in the poets I most identified with. How well I understood Theodore Roethke’s fall in “The Lost Son”:

At Woodlawn I heard the dead cry:

I was lulled by the slamming of iron,

A slow drip over stones,

Toads brooding wells.

All the leaves stuck out their tongues;

I shook the softening chalk of my bones,

Saying,

Snail, snail, glister me forward,

Bird, soft sigh me home,

Worm, be with me.

This is my hard time...

At harder moments when the cold closed in, the poetry of a Sylvia Plath could be lethal.

And the message of the moon? Blackness —

blackness and silence.

--The Moon and the Yew Tree”

But do you know what was worse? I was lazy. If there was an easy way to forego training and start hitting the real stuff, I was game. The lifestyle of Writer appealed far more than the drudgery of training to become one. Studiousness, my only competency, was complicated by an arrogance that said there was really no need to study further.

I didn’t know it, but I was ripe for a sea change. Spring arrived and I met a woman at a party. We talked late, exchanged phone numbers, had lunch, walked spring streets. Spent the night together. I woke in a strange, sun-soaked world where none of my words fit. How arid and dim my former world seemed, how ill-fitting those solitary adjectives! This woman came from beyond the college pale, a high school dropout; my courses had taught me nothing about making love. I had no vocabulary for such immediacy, no dark flavors, too few vowels. I fell short. She announced plans to leave for Los Angeles to live with a brother. I was wild, I babbled, I hurled my entire art at her to convince her to stay: but in seven days she drove off. My world became silent again.

I got drunk that day. Cried, raged. I had no words for the sulphur of those feelings. Poetry couldn't refine their torrent without damming the source. Outside it rained and rained and rained. I strapped on my guitar, plugged into my amp, cranked it up and began to play, not with dexterity or grace but with the singular fury of rock and roll: a black horse pounding wild tundra, a dragon belching molten fevers at the moon. Here was pure verb, whole motion. The notion of writing was eclipsed by a wetter, warmer, wilder moon. I had come to a fork in the road, and the sinister, mistral way seduced me.

That night I took a bus downtown. Lights of the city blurred surreal through the wet window. I got off at the park, deserted at that late and raw hour. Empty but for the initiate, the desperate. My shadow leaped before me then shrank as I passed under the sidewalk lamps.

A sound was slowly building up ahead, at first only a whisper between the hiss of wet tires on the downtown streets. As I walked closer, it developed, adding lower tones. Billows of mist shrouded the lamps. There was a rumbling in my feet.

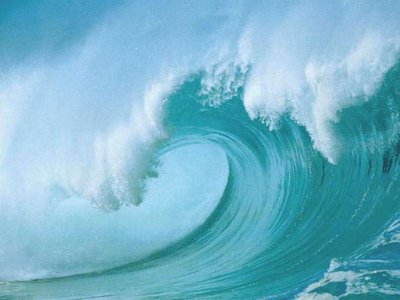

I came to the bridge. The Spokane river hit the falls with a fundamental roar, engorged with spring runoff from the mountains outside town. Two weeks ago it was a frail ribbon snaking around icy boulders on the riverbed; all that disappeared under a black assault of water that hurtled over the falls into crashing smithereens. Stinging mist choired up from the devastation. I stood on that shaking bridge, one with the coiled roar. The river rushed toward me, through me, it hauled me seaward. I was gone. I flowed south, to spring, to sun, song, communion. On and on and on!

Ah, I drank. Insatiably I drank.

But I was filled up also, with too much

World, and, drinking, I myself ran over/

-- Ranier Maria Rilke, World was in the face of the beloved,” (transl. Steven Mitchell)

On a rainy afternoon in late October 1986 I walked Cocoa Beach with a German woman. Sheets of rain whipped ashore, fled, jagged angels of the dying year. The woman walked ahead of me, tall and frail, silent, shelled in her mood. Her blonde hair whipped everywhere in the wild wind.

She would fly back to Germany the next day.

Gulls flew over in formation. Sullen waves plashed ashore, hissed over my toes exhausted, receded. The sad rhythms of that day remind me of an I Ching reading I’d cast sometime back then: K’an, the trigram of the watery Abyss doubled. It meant danger everywhere, the heart drowning in bankrupt passions. Surrender is the only escape, it advised.

I wanted to, but I was clinging desperately to the tattered remnants of the belief that had led me to that beach. My third rock-n-roll band had ground to dust the summer before without ever turning a dime. I would not start again. The women were gone too, so many slim bandwidths of joy, a rare night’s harbor gone dry. The closest relationship I’d seen in a long while walked with me that day, looking across the sea. Nothing I could say. I didn’t believe much any more in drinking, either; once a catalyst, it had become the warden of my days.

Rain picked up again. The woman had almost disappeared in it. Through the mist she seemed almost birdlike, both child and specter, ready at any moment to lift her wings and fly far away.

During that sad season, I finally admitted that the experience I had set out to discover had become a dangerous addiction. An addiction, I found, is a short cut leading to a cliff. The golden moments I sought -- a crescendo onstage, one night in an affair -- had grown faint, became memories, fantasies, then bitter ironies. Those moments weren’t something to be gambled for; rather they were summations of a wholly other order that I avoided, terrified of its demands, its banality, its small incremental rewards. Those moments arrive after the work. As long as I believed otherwise, life would be my enemy. I was swimming against the real current.

The woman turned around and walked back. She wanted to go. There was a question in her eyes at first; but as she got closer it drained away. Finally her eyes were as gray and empty as the sea. Fine, I said. We headed for my car. We were soaked by then, sharpening the wind’s chilly blades. We said nothing more. We got in my car, drove back the long miles of scrub and saw palmetto to Orlando. It was raining when we got out in the parking lot where she had parked her car. She hugged me, smiled distantly, then walked away. I leaned against my car and watched her unlock her car, get in and turn the ignition. She was a ghost behind a wet window, a fragment of memory, three curving strokes of blonde hair and grey eyes disappearing in shadow. She drove off into the great silence.

Philosophy, or a discrimination of truths, began to come to me some months later, following a furious spate of final drinking I somehow survived. During long quiet nights in the winter of 1987 I began to take stock. It was clear to me that the turn I had taken ten years before had been the wrong one, but understandable. The acute and painful inwardness of my college days had created a condition for learning words. But I had focused on words to the exclusion of all else; so when the rites of spring flooded me, I believed there was no way I could write another word without those sweet waters. I had believed my words needed world if they were to have any meaning.

So I set out for the wild, initiate to a relation I sensed but rarely found. It was fun for a while. But I was looking in the wrong places. I had literalized a dazzling experience of life into dull repetitions. The endless outpour was like a wound unable to coagulate and festering easily. High art fell to low folly: meaningless experience played itself out just as false and dangerous as my former position of extreme introversion.

Two alternatives remained: oblivion, or a shared middle ground. It was possible that word and world might find each other through a mediation. I didn’t see it quite so clearly then, but the sense was strong enough to point a new direction. I was free to enter the mainstream; I could get to work.

And so the desire to write returned. I bid on a position in my company that involved more writing. Within a few years this led to another in employee communications. From it I plan to get the experience and training to launch a broader, more independent writing career. Learning to write apropos to the workplace puts word in the service of world: the end directs the means.

The desire to write poetry also returned, fostered by a wakened passion for literature. Saul Bellow said, “A writer is a reader moved to emulation,” and reading great poetry underscored the poverty of my own. I was called to work harder. Poetry puts world to the service of word; I take the events of my day and strain them through a net of words. How wonderful to find something gold wriggling in the net.

In my reading I discovered the German poet Rainier Maria Rilke; his Sonnets to Orpheus are still my favorite group of poems. In a way, these poems arrived readily to Rilke; he characterized the experience as “the most enigmatic dictation I have ever endured and achieved.” But we must remember these poems came to Rilke late in life, the harvest of unparalleled attention and effort

.

The poems are about their own domain: poetry, writing’s primal father, a magic that so enchanted the world that animals, trees, even stones stopped and turned to listen. Word and world harmonized in the song of Orpheus.

Orpheus paid dearly for this magic. He lost his wife Eurydice on their wedding day. Grieving, he sought her in the underworld, enchanting all the dread and dead with his song; but his own eagerness to look upon her face doomed his quest. He emerged alone. Later she woke — in his song.

Rilke understood the cost of poetry. But by looking deeper and deeper at what he feared — the fatal embroilment of love, the terrible silence of the natural world, the insinuating tendrils of death— he was able to make the strongest affirmation of the unity of life and death in art.

... Song, as you have taught it, is not desire,

Not wooing any grace that can be achieved;

Song is reality. Simple, for a god.

But when can we be real? When does he pour

The earth, the stars, into us? Young man,

It is not your loving, even if your mouth

Was forced wide open by your own voice — learn

To forget that passionate music. It will end.

True singing is a different breath, about

Nothing. A gust inside the god. A wind.

“Sonnets to Orpheus” I.3

(transl. Steven Mitchell)

For Rilke, truth, or “true singing,” goes beyond word and world, beyond technique and experience. It is the music of the world as it is. The writer polishes a mirror and holds it up to the world. If the reflected music is real, all creation gathers around to listen. Simple, for a god, but a life’s work for one who is just learning to write.

<< Home