Freighting the Whale V: The Rider

No mercy, no power but its own controls it. Panting and snorting like a mad battle-steed that has lost its rider, the masterless ocean overrruns the globe.

- Melville, Moby Dick

***

I read this Saturday afternoon, lounging on the couch watching the first round of football games (few surprises, just Oklahoma losing to TMU, blowouts by USC and Iowa and Georgia, a close one between Colorado/Colorado State providing the main semblance of entertainment) and flipping back to disaster footage on the cable news networks. Outside it clouded, rained often, then stayed bleary and drippy; I got my yardwork done early on Saturday, so the rains were quite welcome.

Melville's identification with his theme took him from being on the boat dragged by a harpooned whale -- full of the merciless and bloody pathos of whale-killing in those days -- and then cranking up the registers by descending down the past, following the whale, riding the whale, living in the whale, becoming the whale, its voice, the organum of the abyss.

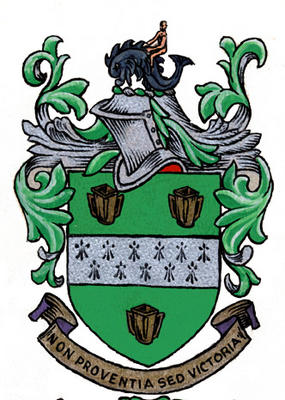

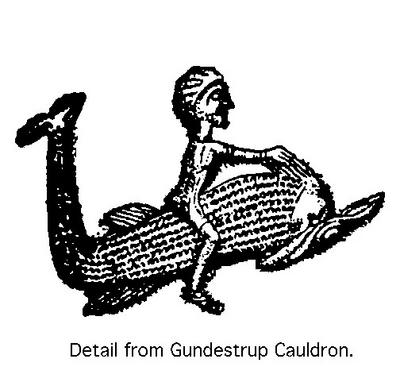

Here I'll admit there is a whale-rider on my father's ancient Gaelic crest -- a name which we have a bastardized English equivalent of, and who knows if there is any bloodline left -- so I'm fascinated with the idea of riding a whale or fish as a primary mythologem; and as I spend hours now trying to figure out where things are headed for me on paper, there is a futurity to the image -- as if by pondering back I ponder the way forward.

One image of genius is that of a dolphin rider -- Arion, archetype of the singer, was carried to shore by a dolphin (after being thrown into the abyss of the sea by pirates); and then there are the dolphin-riding cupidon on Roman gravestones, the genus loci ferrying the soul of the departed on to heaven. My father's family apparently had bardic roots -- three drinking horns also on that crest, the cups of wine, women and song -- we also know of harpers and fiddlers, poets and lawyers along the way -- so weave that strand into the meditation.

Can genius be read as a selfless identification with one's work? Does it connect us with the most primary of sources, as Eros himself was born from the world egg of Phanes, cracking things wide with surprise and delight? Does all good work require so primary, thus watery, a connection? Emerson so believed: "Wisdom consists in keeping the soul liquid," he wrote in his Journal of 1842. "There must be the Abyss, Nyx, and Chaos, out of which all things come, and they must never be far off. Cut off the connection between any of your works and this dread origin, and the work is shallow and unsatisfying."

I got confirmation of this thought on Saturday soon after I switched texts and resumed my reading of Walter Jackson Bate's biography of John Keats, and read that when Keats was 15 he was forced to leave school when his mother died (his father had already passed away) and seek employment to help care for his orphaned brother and sister. He kept reading, though, and ferociously; and he would visit his old schoolmaster, who introduced him to many texts.

One of them was Spencer's Faerie Queene, and it was in reading this old text that Keats's future enterprise seemed to suddenly blossom. The schoolmaster Clarke reminisced many years later about Keats to one of his biographers; the young man's reaction to the book was,

"as a young horse would through a spring meadow -- ramping! Like a true poet, too -- born, not manufactured, a poet in grain, he especially singled out epithets for that felicity and power in which Spenser is so eminent. He hoisted himself up, and looked burly and dominant {he was never more than 5' tall}, as he said, "what an image that is -- 'sea-shouldering whales!''

According to another biographer quoted in Bates,

"It was "Faery Queene" that awakened {Keats's } genius. In Spenser's fairy land he was enchanted, breathed in a new world, and became another being: till, enamored of the stanza, he attempted to imitate it, and succeeded."

Spenser's retelling of an old Celtic tale opened a magic cellar door in his own imagination, unleashing from below an equally if not wilder sea of invention.

Bates confirms the genius of identification as the agency of Keats's unparalleled development as a poet. Remarking on the oft-repeated story above, he said that it shows in Keats "the sort of empathy -- the adhesive, imaginative identification -- the increasingly marked (his) own poetry and that later deepened in his clairvoyant understanding of Shakespeare."

Negative Capability is just that -- "The ability," as Bates put it, "to negate one's identity, to lose it in something larger or more meaningful than oneself." To step aboard that big fish and ride it to hell, highwater and whatever Truths a human heart can abide.

<< Home