Freighting the Whale VI: The Bard as Brute

In "The Poet," Emerson called this Capability "abandonment to the nature of things." "As the traveller who has lost his way throws his reins on his horse's neck and trusts to the instinct of the animal to find his road, so must we do with the divine animal who carries us through this world. For if in any manner we can stimulate this instinct, new passages are opened for us into nature; the mind flows into and through things hardest and highest, and the metamorphosis is possible."

Interesting that Emerson sides the activity with the animal and not the angel, or, if divine, astride a divine brute. Whale, or man as demiurge, as words of basalt and brine and unsounded abysms carved?

Both Melville and Keats crossed a great water in the works. The dove on those verbal whales to depths perhaps only Shakespeare, whom both so revered, had formerly been able to reach.

Perhaps it was Shakespeare himself who was the whale that Melville rode, a Leviathan of language at the bottom of our selves(or our sense of ourself, if you take Harold Bloom's contention that Shakespeare created our sense of human being.) Certainly the man was daunting -- Bloom says the Bard had a vocabulary of more than 21,000 words, and his creation of Hamlet rivals that of Jesus as the central figure of Western consciousness, embodying "a vision that is everything and nothing, a person who was ... everyone and no one, an art so infinite that it contains us, and will go on enclosing those likely to come after us." (Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human

But what is amazing -- and, I believe, essential -- is that both Melville and Keats found their Shakespeare -- himself no academic -- outside of the academy; they were both unschooled in their approach, identifying and ratifying with him out of their own raw and vital natures. Their embrace of Shakespeare occurred at an animal level.

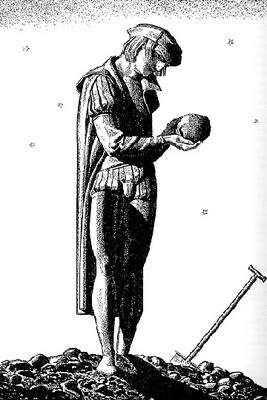

Melville read and re-read Shakespeare's plays in the months before and during the writing of Moby Dick, and remarked on the plays that what he found most vitally in them was not purity of drama or a broad understanding of human psychology but "those deep far-way thing in him; those occasional flashings-forth of the intuitive Truth in him; those short, quick probings at the very axis of reality .... "the things which we feel to be so terrifically true" that no merely good man would ever speak them. Melville found his Vedas at the bottom of Shakespeare, in his terrifying depths. One of my favorite passages from Moby Dick, which I've quoted here before, comes when the crew of the Pequod have caught their first whale; the head is cut off and tied to the ship-- later it will be mined for the spermacetti trapped in the honeycombs of its skull while the crew work at stripping the blubber from the corpse and boiling it down for the whale oil. After the crew retires below decks, Ahab comes upon on the deck and contemplates the massive had hanging there, as if he were Hamlet observing the huge skull of the jester Yorick-or that of Shakespeare -- certainly the soliloquy is Shakesperean at its darkest and deepest:

"It was a black and hooded head, and hanging there in the midst of so intense a calm, it seemed the sphynx's in the desert. 'Speak, thou vast and venerable head,' muttered Ahab, 'which, though ungarnished with a beard, yet hear and there lookest hoary with mosses; speak, mighty head, and tell us the secret thing that is within thee. Of all divers, thou hast dived the deepest. The head upon which now the upper sun now gleams, has moved amid the world's foundations, where unrecorded names and navies rust, and untold hopes and anchors rot, where in her murderous hold this frigate earth is ballasted with bones of millions of the drowned. There, in the awful water land, there was thy most familiar home. Thou hast been where bell or diver never went, hast slept by many a sailor's side, where sleepless mothers would give their lives to lay them down. Thou saw'st the locked lovers leaping from their flaming ship; heart to heart they sank beneath the exulting wave; true to each other, when heaven seemed false to them. Thou saw'st the murdered mate when tossed by pirates from the midnight deck; for hours he fell into the deeper midnight of the insensate maw; and his murderers still sailed on unharmed -- while swift lightnings shivered the neighboring ship that would have borne a righteous husband to outstretched, longing arms. O head! thou hast seen enough to make an infidel of Abraham, and no syllable is thine!"

***

That's a dark dark truth, ainit? A mad truth, and ripe with knowledge of the far lands, bournes which no mortal traveller returns from. (Remember, Hamlet's soliloquy holding the skull of Yorick happens just after his own sea voyage.) And when Oran's head alights from the dirt of St. Columba's abbey, offering news of the Celtic hell that St. Columba was so eager to learn of, the truth was not one the saint could much abide ("Heaven is not as you have said, nor is hell as you have supposed," went the line), and thus the dead monk was promptly reburied.

Bloom again: "The ultimate use of Shakespeare is to let him teach you to think too well, to whatever truth you can sustain without perishing." Melville and Keats gain those truths at sea -- not in the aeries of thought, not from what they knew, but with skulls that poured far countries of brine.

<< Home