Intermission, with Big Stones

Something is still brewing in the thigh of the All-Father, so, in lieu, as intermission music, these early man-poems, and a much much earlier man-tale, the fish all these foundational poems ride ...

MAN

1988

Fuck these poetics, lets

go where it’s so hard

it hurts:

there’s this lead log

swinging between my legs,

calling me to rise up in the night.

Such a small thing! you say,

half a hand and less a shoe.

Perhaps to you; but it’s the

stone bear I live in, my blood’s

dark, purple prowling.

Now, remember,

I’m always thrusting,

being a dick at both romance

and career, vengeful on

the backcourt, ramming the road

with my car.

It’s always

the same, this fucking!

Sorry. I can’t help it.

Every second is wet or

pendulous, there’s a proud

nipple rising up at the end of

every sheer sentence.

The sun-clit rides a boat of fire

and the moon

I love to pound in the dark.

My heads smile at each other.

Their three eyes wink like frat

brothers.

My eyes all see the same

and my heads both think they’re swell.

One head thinks for the other

(though which, I’m not sure).

My hands celebrate the memory of

pressure, the hammering of birth:

I’ll be damned

if I’m not burrowing and sweating

the brine inches home!

How I love the body’s

vaginas, its tight loca -

a virgin’s sealed cunt

or the practiced mouth of a whore,

big boobs or wobbly

ass-cheeks heaved together, a clenched

fist, the lonely space

between two toes!

Deeper and deeper I push, hard

into the home spaces, greased

with the

oils of spit and pussy-juice,

hot as lava on the homeward thrust,

as far as I can go . . .

I close my eyes to see

the roaring redlights, I feel

my balls shudder

and then I’m spouting the sea,

touches she-in-all in

that second or two of coming -

and falls -

too far -

Well, it’s fucking mainly,

and I’ll do it for love

and I’ll do

it for fun and I’ll do it with

you or I’ll do it alone and

I don’t care much what shatters along the way.

I don’t give a fuck.

All I know

is that I must, I’ve got a shark in me

that eats and swims and can never

stop. If you say no, I’ll

just take my frenzy somewhere else.

So c’mon, baby, spread it wide.

Receive me.

God’s calling.

CLOSING THE CASTAWAY BAR

1989

Oh fuck it all, he sighs, and so cuts his sleek black

car through the night. It's cool inside. Nothing intrudes.

Instruments on the dash glow green their phosphor

ghosting his hands. The radio plays old songs.

Miles of road thread back into the corrupt interior.

Home is behind, a throttle of malls and

the ceaseless traffic of broken things.

A battered rondo of bars and bottle clubs.

He flees for the ocean like some latter-day Jonah,

scheming rebirth in the pink cerulean surf of morning.

He enters the beachside town. Streetlights approach

and fan over the windshield. Lowering the window:

the ocean night crowds in warm and briny gusts.

The street deadends at a bar called The Castaway.

Yards away surf wrestles the shore. The bar is decorated

with fishing nets and sweet curving conch shells.

He finds an empty stool next to a battered bar.

The barmaid takes a shine to him and buys him shots

of tequila. The gold fangs pierce, glow. He talks

openly with her as he does when drink and sex coil

his heart late at night. Nice ocean haul, he thinks.

Of course, any mermaid will do. Must do.

The hours dissolve darkly to closing time. He finds himself

laying on a table close to the surf. Muscular breezes work

the naked beach. A zipper of silver paves black water

to a zenith moon. He remembers the barmaid and the bruise

on his cheek. Gulls slide overhead like beggar angels.

Is this night the belly of the whale? Even in his stupor,

he’s sure it is. The poor beast lurches and rolls,

swims shitfaced, nauseated utterly by him. What did

he expect? He's the worm at the bottom of every

bottle. He sighs wearily. Same guts, different bar.

The ocean sings to him in wind and surf like

a mother's soft birthday song. Rising out of nothing's breakers.

He feels he should join in, too, sing back brokenly and

tearful, but his tongue is like whale fat. Doesn't matter, though,

because the sea isn't singing for him, any way, nor nor for the

locked door of the bar, not for the gull that’s crapped on his chin,

nor the hard breezy night. Not for the all world's dark shore.

But will our hero ever learn? What? is his last thought there on the

table, lulled by the boneless choir of the sea. Fade to black

as our hero descends the welcoming gullet.

THE CLINGING

1988

Why are we always clinging, clinging to what we can?

Such a useless gesture . . . Remember birth? how we

were squeezed down those gripless walls?

Wasn’t that the essential lesson? And do we ever stop

sliding? It’s just goes on, one long hilarious

tumble into the grave’s sudden mitt.

Our hero has clung heroically for all his life. Raised

in a Depression home, he learned the trade of salvation

through ownership. Now 50, he’s appropriated well:

a successful career in sales, a beautiful house in a ritzy

subdivision, some sizable chunks of real estate, a Jaguar.

A new wife, young, pretty, manageable.

He had expected his hunger to eventually

sate on this life of big-ticket meals, but every morning

his hunger renews at first light. Predator by day.

He clings not merely to substance but context as well:

club ownership policies, presidential politics, county

zoning pecadillos, lifetime subscriptions, sworn affidavits,

affiliations and memberships, yellowed boxes of memorabilia.

Capitalist of the heart -- grabbing and grubbing all away!

To keep it all intact, he makes deals, he cements things

with shit and blood and semen. His lawyer and accountant

have license to slice off hunks of his ass, so long that

his affairs are presentable. His pretty wife can shop

his Gold Card purple as she neither leaves nor loves him.

If his kids smile at least when his mother comes to visit

they can smoke dope and fuck whoever in their rooms

while he watches the 11 o’clock news.

All in place!

Every autumn, he rides with busloads of drunk boosters

to football games at his alma mater. They all dress

in cartoon blues and oranges, they fill the stadium.

He bets and loses huge sums of money. He gets drunk

on the way home and sings with the boys.

They all know about his secretary, how she can’t type well

nor even take a decent telephone message,

but boy does she take dick-tation! On quiet afternoons

he fucks her on the conference table. Daddy, she whispers,

daddy. Her face clenched and closed as he pumps her.

He lets her cling until her clinging no longer incites him.

On late Saturday afternoons in the summer

our hero barbecues in his back yard. His new wife lounges

by the pool with fashion magazines and manhattans.

He drinks iced vodka as he turns the red spits of meat.

Fat hisses and smokes, rising to no god. Tonight they

are alone: his kids are partying at a beachfront hotel.

He imagines them climbing on balcony

railings, throwing up in elevators, getting the clap.

Fuck 'em. They cling to his wallet like rats.

The Florida sun falls fat and red into the far

bending palms. Sizzle of meat, easy listening, biting

sips of cold booze. Air conditioners and pool pumps

drone around the neighborhood. He tries to add it

all up, this continual assault on Easy Living --

a brutal, a contourless climb. He thinks

he should be on the verge of recovering

something -- that soon he will arrive at some suburban

womb of things, like a lone salmon finally in home waters.

Will he then be able to rest? The music sweetly

segues from song to song. All in place, so still, so immanent . . .

But our hero is already far away, plotting, casting

his desperate silver threads at the sun. The sun sails on

in cruel silence, eternal inches from his grasp,

bloodying the dark horizon.

CLOSING THE DEAL

1990

You stand at the window of your

hotel room, naked and wet from the pool.

Heavy curtains pull back to reveal

palm trees winnowing lazy fronds.

A fountain spouts glass into the

brilliant Florida sky. You feel its deeper

possibilities lift and cast you,

like spray, into the sun. A yearning

infinitude. Your skin burns with it.

All this first class treatment proves

how weak their deal really is:

the black jet that muscled you south,

this hotel of marble and brass,

bright servants, iced salmon

on pale porcelain, golf fairways

neater than carpet, poolside women

in neon bikinis serene in

the torpor of water and sun.

All of this shouts disaster at you.

Later you head for the bar.

You sit on a wicker barstool

sipping a tall glass of rum and fruit.

A combo pulses moody tropic jazz.

Slowly spinning fans whisper

in their tireless cradles:

first class, first class, first class.

How could they know you’d tremble?

As sheets of satin booze settle

over your eyes, you find yourself

wanting to drowse forever in this descent,

to fall gently on all dotted lines,

a chunk of pineapple sinking in rum,

one with whom any deal can be made:

just pour on that dark bossa nova, bartender,

and let the music fade blue to black.

THE STANDOFF

1990

Taken from a photo in the paper:

a man in a doorway holds a gun

to his head with one hand, in the other a beer.

Two police face him from behind a shield.

I stand at the door, half-in, half-out,

the winter morning jagged and cold

like the snout of this .38 jammed in my ear.

This beerís cold too, each swig

falls slow and mean like Harlem sleet.

But my trigger fingerís colder. Frozen.

Funny, no matter which way you point

a gun, this street always stops to watch:

the two cops cowering behind their shield,

squad cars phalanxed on the sidewalk,

radios squawking, lights strobing bluered bluered,

sunglasses and shotguns glittering

like broken glass in the hard morning sun,

beyond them camera crews edging closer

with the crowd, jostling for a gape at splatter.

Only the paramedics seem bored,

smoking together by the ambulance.

The shield before me talks like a TV daddy,

trying to babble me down from here

with such shit about its not too late

and give yourself another chance. I mean really.

But that dull plate looks like my old man,

a shadow in steel that canít be shattered,

sending me off again with that cold winter stare.

Drunk father, dark father, take no prisoners, rage.

How long? An hour, two? It isnít up to me.

I just stand here like the piano man

at the Pussy Prowl on stage between the babes,

that old sorry ass blues mooning

from my fingers like a shot of bad whiskey.

Hold me up to the light and you see

the same malt nigger nothing.

You'd pull the trigger too.

It's too cold for the grace my momma

said would always come if we prayed.

This angel just wants my ass.

A wind off the lake sweeps in,

swirling up litter up in tight funnels,

and a truck backfires, startling the crowd:

Then suddenly itís happening,

everyone screaming Do It, Fucker,

the cameras click and whirl like startled pigeons,

and the cops behind the shield cower holy Jesus,

and the winter sky barrels down on the city

like a molester on a shivering pale girl,

and blood erupts in the stone of my finger,

screaming nothingís getting in, man

I take no prisoners

I squeeze my eyes shut and

shut and shut

and shut

and

THE VIRGIN AND THE DYNAMO

David Cohea

1988

I've been fucking the Madonna

in a frenzy of beds and sweat,

mounted to a crucifix of immortal desire,

unharbored, unholy, messiah and nail --

1.

I met her when I was thirteen.

Back then her name was Sue.

We swam in the pool

in my back yard.

Her body flashed wet

and dazzling in a neon

bikini as she giggled out

of my reach. How my cock

leapt after her, month after

masturbating month, hurling

a joyous fury of sperm into the water.

2.

It is years later and very late at night.

A woman holds my cock in her hand,

pistoning its floral head in her mouth.

I fuck her later on my mother's bed,

her heavy breasts heaving as I thrust.

Salmon leap over us, trailing gin-tasting

waters. There is a half-empty bottle

on a nightstand; inside, a full moon rises.

I hunt on the moon.

Behind me vultures peck at bloody,

glistening eggs. They croak and caw,

sounding like high school buddies trying to

scrabble out of their lockers.

I reach for a magnificent staff in the dust.

Neon signs blink in craters.

I am crying, for I have been

re-united with my foreskin.

Winds pick up and maul the father desert.

Tumbleweeds bound past trailing

shreds of red satin and panty hose.

I approach a bleached shack.

The door is open but women guard the entrance.

I can't remember the words to say and the women

curse me, pitching dead rats at me.

I flee.

3.

The moon is the screen

of a nine inch b&w TV

several feet from this bed.

It is 3 a.m.; a 70's comedy

babbles canned laughter.

I lay on hair, long, long hair

that flows like water

from my head, my face, my

chest, my crotch, my legs.

It has tangled some struggling thing

that makes muffled feminine protests:

what if the kids hear, I'm on my period,

I don't have any protection,

don't you think we should wait

to get to know each other better?

The woman's ass protrudes from all

this hair, framed in scant black panties.

Darling fig leaf, what a beacon her shame!

I run my fingers under the cool material,

over pliant, soft skin, dipping my finger

into swimming lava. The bed hardens,

plunging me into the red cavern.

Here the air is hot and smells of the distant sea.

Tears fill me: home!

I watch the woman's face as I shudder then spasm.

Her smile melts and becomes a snake that

tightens round my throat, becomes an

umbilical cord knotting me in the ground.

A stone man crashes out of the forest

swinging an axe and severing the snake's head.

The head rolls along down a hill and into a boat.

I chase after it but the boat slips free

and floats out into Chinese waters.

Tall cliffs hump above dense mist.

I swim after the boat, calling out my own name.

4.

More years pass. Spring arrives.

I walk with a woman I call my love.

She holds my hand and smiles

although it's a cold day, dark and damp.

We walk out on a bridge

that spans a pounding river.

Its roar encloses us as we kiss.

I lean her back:.

Her eyes widen into moons when she falls.

We will meet again, I call . . .

The mist is alcoholic, turning

to hard squall which batters down the bridge.

I wash away in tears.

5.

Summer.

I swim in an Olympic pool.

The water is blue.

I stroke slowly, counting off laps.

Sunlight wrinkles on the pool floor

in a mosaic of delight.

Sweet with exhausting,

I climb out and lay on a deck chair.

My towel is blue. The sky is blue.

Blue water coils through my blood.

A smiling blonde in a black string bikini

straddles my chest. Her eyes are ocean.

She smells of cocoa butter and is very, very tanned.

She rocks on my hips, moaning her name.

Bossa nova fills the air.

I sip dark rum mixed with her vaginal fluids.

There is diving board a hundred feet

above a glass of water.

Everyone from the bar is on the ladder,

joking and pitching cherries at each other.

Couples giggle and hold hands mock-solemn,

then bounce off me and fall

smashing like melons on the concrete below..

6.

I am in a drunk blackout at Daytona Beach.

It is late at night. Motley Crue

blasts from the windows

of passing Firebirds and 'Vettes.

Around my neck I wear a necklace

of withered, bloody nipples.

The crotch of my shorts has been cut out.

Bartenders work in the surf, dipping up shots.

I have no more money so I offer my car,

rolling it into the water. Everyone cheers.

Topless dancers fandango for me,

their fangs brilliant in the moonlight.

I thrash and moan and hump the air.

Bouncers snort like bulls and race toward me.

At some dead a.m. I wake, rolling onto

the concrete in some parking lot.

My face is bloody my hands are bruised.

I am in a graveyard of lost sons

howling from patrol cars sleek as barracuda.

7.

Dawn.

I'm in bed with a woman I take

from time to time, usually after all the bars

have closed and every other woman I can think of

has refused me. My last-ditch fuck.

She lives in an old house.

A corrupt smell rises from the basement.

Candles burn in every window.

The woman is plain, ass and belly flaccid,

her face too homely for the lava I seek.

She falls far to welcome me.

I drink a beer, smoke a joint. She waits.

I push her down onto her couch.

Fantasy women sashay on MTV.

I fuck her snatch; too bored to come,

I try fucking her tits.

There is no warmth, no wet,

but the motion is cruel enough

to keep me hard. Finally I jam

my cock in her mouth and force her

o swallow my come.

There is nothing in the moment,

no delight, no crooning melt.

She runs to the john to retch

and smoke fills the room, thick and black.

I fall asleep, finished at last,

mounted by flames.

DARK SAUCER

1990

Sweetface the stray cat we feed is in heat.

Three tomcats surround her, like mangy lions,

waiting for her to tire. Then they take turns on her.

They've been feasting on sore Sweetface for three days now.

Caterwauling yowls tear into our dinner.

My wife runs outside with stones she's collected, and

the tensed cincture of fur scatters. Pale eyes stare

patiently from under car and house, behind the garage.

When my wife sits back down she glares at me.

I say look, hon, Sweetface isn't neutered, they can't help it.

Our daughter tries to watch the action in the window.

Later I walk to the corner store for milk.

As I open the door a woman exits: black dress,

blonde hair lifting in the draft, pallor, perfume.

Our eyes lock for one departing second. Reaching

for the cooler my hand is pale and calm as bone.

I swing the cold jug of milk as I walk back.

It's a warm night, humming and sweet. On our porch

my daughter dances to music on a small radio.

She's 12, barely innocent in the porchlight.

A Chevy roars past, and the cats are at it again, pelting

the night with howls, lapping their dark saucer of milk.

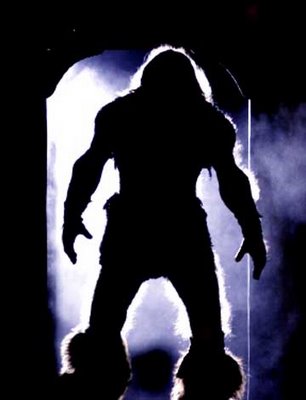

IRON JOHN

from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, 1812

by Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm

ONCE UPON a time there lived a King who had a great forest near his palace, full of all kinds of wild animals. One day he sent out a huntsman to shoot him a roe, but he did not come back. "Perhaps some accident has befallen him," said the King, and the next day he sent out two more huntsmen who were to search for him, but they too stayed away. Then on the third day, he sent for all his huntsmen, and said, "Scour the whole forest through, and do not give up until ye have found all three." But of these also, none came home again, and of the pack of hounds which they had taken with them, none were seen more. From that time forth, no one would any longer venture into the forest, and it lay there in deep stillness and solitude, and nothing was seen of it, but sometimes an eagle or a hawk flying over it.

This lasted for many years, when a strange huntsman announced himself to the King as seeking a situation, and offered to go into the dangerous forest. The King, however, would not give his consent, and said, "It is not safe in there; I fear it would fare with thee no better than with the others, and thou wouldst never come out again." The huntsman replied, "Lord, I will venture it at my own risk; I have no fear."

The huntsman therefore betook himself with his dog to the forest. It was not long before the dog fell in with some game on the way, and wanted to pursue it; but hardly had the dog run two steps when it stood before a deep pool, could go no farther, and a naked arm stretched itself out of the water, seized it, and drew it under. When the huntsman saw that, he went back and fetched three men to come with buckets and bail out the water. When they could see to the bottom there lay a wild man whose body was brown like rusty iron, and whose hair hung over his face down to his knees. They bound him with cords, and led him away to the castle. There was great astonishment over the wild man; the King, however, had him put in an iron cage in his court-yard, and forbade the door to be opened on pain of death, and the Queen herself was to take the key into her keeping. And from this time forth every one could again go into the forest with safety.

The King had a son eight years old, who was once playing in the court-yard, and while he was playing, his golden ball fell into the cage. The boy ran thither and said, "Give me my ball." "Not till thou hast opened the door for me," answered the man. "No," said the boy, "I will not do that; the King has forbidden it," and ran away. The next day he again went and asked for his ball; the wild man said, "Open my door," but the boy would not. On the third day the King had ridden out hunting, and the boy went once more and said, "I cannot open the door even if I wished, for I have not the key." Then the wild man said, "It lies under thy mother's pillow, thou canst get it there." The boy, who wanted to have his ball back, cast all thought to the winds, and brought the key. The door opened with difficulty, and the boy pinched his fingers. When it was open the wild man stepped out, gave him the golden ball, and hurried away. The boy had become afraid; he called and cried after him, "Oh, wild man, do not go away, or I shall be beaten!" The wild man turned back, took him up, set him on his shoulder, and went with hasty steps into the forest.

When the King came home, he observed the empty cage, and asked the Queen how that had happened. She knew nothing about it, and sought the key, but it was gone. She called the boy, but no one answered. The King sent out people to seek for him in the fields, but they did not find him. Then he could easily guess what had happened, and much grief reigned in the royal court.

When the wild man had once more reached the dark forest, he took the boy down from his shoulder, and said to him, "Thou wilt never see thy father and mother again, but I will keep thee with me, for thou hast set me free, and I have compassion on thee. If thou dost all I bid thee, thou shalt fare well. Of treasure and gold I have enough, and more than any one in the world." He made a bed of moss for the boy on which he slept, and the next morning the man took him to a well, and said, "Behold, the gold well is as bright and clear as crystal; thou shalt sit beside it, and take care that nothing falls into it, or it will be polluted. I will come every evening to see if thou hast obeyed my order." The boy placed himself by the margin of the well, and often saw a golden fish or a golden snake show itself therein, and took care that nothing fell in. As he was thus sitting, his finger hurt him so violently that he involuntarily put it in the water. He drew it quickly out again, but saw that it was quite gilded, and whatsoever pains he took to wash the gold off again, all was to no purpose.

In the evening Iron John came back, looked at the boy, and said, "What has happened to the well?" "Nothing, nothing," he answered, and held his finger behind his back, that the man might not see it. But he said, "Thou hast dipped thy finger into the water; this time it may pass, but take care thou dost not let anything go in." By daybreak the boy was already sitting by the well and watching it. His finger hurt him again and he passed it over his head, and then unhappily a hair fell down into the well. He took it quickly out, but it was already quite gilded. Iron John came, and already knew what had happened. "Thou hast let a hair fall into the well," said he. "I will allow thee to watch by it once more, but if this happens for the third time then the well is polluted, and thou canst no longer remain with me."

On the third day, the boy sat by the well, and did not stir his finger, however much it hurt him. But the time was long to him, and he looked at the reflection of his face on the surface of the water. And as he still bent down more and more while he was doing so, and trying to look straight into the eyes, his long hair fell down from his shoulders into the water. He raised himself up quickly, but the whole of the hair of his head was already golden and shone like the sun. You may imagine how terrified the poor boy was! He took his pocket-handkerchief and tied it round his head, in order that the man might not see it. When he came he already knew everything, and said, "Take the handkerchief off." Then the golden hair streamed forth, and let the boy excuse himself as he might, it was of no use. "Thou hast not stood the trial, and canst stay here no longer. Go forth into the world, there thou wilt learn what poverty is. But as thou hast not a bad heart, and as I mean well by thee, there is one thing I will grant thee; if thou fallest into any difficulty, come to the forest and cry, 'Iron John,' and then I will come and help thee. My power is great, greater than thou thinkest, and I have gold and silver in abundance."

Then the King's son left the forest, and walked by beaten and unbeaten paths ever onwards until at length he reached a great city. There he looked for work, but could find none, and he had learnt nothing by which he could help himself. At length he went to the palace, and asked if they would take him in. The people about court did not at all know what use they could make of him, but they liked him, and told him to stay. At length the cook took him into his service, and said he might carry food and water, and rake the cinders together. Once when it so happened that no one else was at hand, the cook ordered him to carry the food to the royal table, but as he did not like to let his golden hair be seen, he kept his little cap on.

Such a thing as that had never yet come under the King's notice, and he said, "When thou comest to the royal table thou must take thy hat off." He answered, "Ah, Lord, I cannot; I have a bad sore place on my head." Then the King had the cook called before him and scolded him, and asked how he could take such a boy as that into his service, and that he was to turn him off at once. The cook, however, had pity on him, and exchanged him for the gardener's boy.

Now the boy had to plant and water the garden, hoe and dig, and bear the wind and bad weather. Once in summer when he was working alone in the garden, the day was so warm he took his little cap off that the air might cool him. As the sun shone on his hair it glittered and flashed so that the rays fell into the bed-room of the King's daughter, and up she sprang to see what that could be. Then she saw the boy, and cried to him, "Boy, bring me a wreath of flowers." He put his cap on with all haste, and gathered wild field-flowers and bound them together. When he was ascending the stairs with them, the gardener met him, and said, "How canst thou take the King's daughter a garland of such common flowers? Go quickly, and get another, and seek out the prettiest and rarest." "Oh, no," replied the boy, "the wild ones have more scent, and will please her better."

When he got into the room, the King's daughter said, "Take thy cap off, it is not seemly to keep it on in my presence." He again said, "I may not, I have a sore head." She, however, caught at his cap and pulled it off, and then his golden hair rolled down on his shoulders, and it was splendid to behold. He wanted to run out, but she held him by the arm, and gave him a handful of ducats. With these he departed, but he cared nothing for the gold pieces. He took them to the gardener, and said, "I present them to thy children, they can play with them."

The following day the King's daughter again called to him that he was to bring her a wreath of field-flowers, and when he went in with it, she instantly snatched at his cap, and wanted to take it away from him, but he held it fast with both hands. She again gave him a handful of ducats, but he would not keep them, and gave them to the gardener for playthings for his children. On the third day things went just the same; she could not get his cap away from him, and he would not have her money.

Not long afterwards, the country was overrun by war. The King gathered together his people, and did not know whether or not he could offer any opposition to the enemy, who was superior in strength and had a mighty army. Then said the gardener's boy, "I am grown up, and will go to the wars also, only give me a horse." The others laughed, and said, "Seek one for thyself when we are gone, we will leave one behind us in the stable for thee." When they had gone forth, he went into the stable, and got the horse out; it was lame of one foot, and limped hobblety jig, hobblety jig; nevertheless he mounted it, and rode away to the dark forest. When he came to the outskirts, he called "Iron John" three times so loudly that it echoed through the trees. Thereupon the wild man appeared immediately, and said, "What dost thou desire?" "I want a strong steed, for I am going to the wars." "That thou shalt have, and still more than thou askest for."

Then the wild man went back into the forest, and it was not long before a stable-boy came out of it, who led a horse that snorted with its nostrils, and could hardly be restrained, and behind them followed a great troop of soldiers entirely equipped in iron, and their swords flashed in the sun. The youth made over his three-legged horse to the stable-boy, mounted the other, and rode at the head of the soldiers. When he got near the battle-field a great part of the King's men had already fallen, and little was wanting to make the rest give way. Then the youth galloped thither with his iron soldiers, broke like a hurricane over the enemy, and beat down all who opposed him. They began to fly, but the youth pursued, and never stopped, until there was not a single man left. Instead, however, of returning to the King, he conducted his troop by bye-ways back to the forest, and called forth Iron John. "What dost thou desire?" asked the wild man. "Take back thy horse and thy troops, and give me my three-legged horse again." All that he asked was done, and soon he was riding on his three-legged horse.

When the King returned to his palace, his daughter went to meet him, and wished him joy of his victory. "I am not the one who carried away the victory," said he, "but a stranger knight who came to my assistance with his soldiers." The daughter wanted to hear who the strange knight was, but the King did not know, and said, "He followed the enemy, and I did not see him again." She inquired of the gardener where his boy was, but he smiled, and said, "He has just come home on his three-legged horse, and the others have been mocking him, and crying, 'Here comes our hobblety jig back again!' They asked, too, 'Under what hedge hast thou been lying sleeping all the time?' He, however, said, 'I did the best of all, and it would have gone badly without me.' And then he was still more ridiculed."

The King said to his daughter, "I will proclaim a great feast that shall last for three days, and thou shalt throw a golden apple. Perhaps the unknown will come to it." When the feast was announced, the youth went out to the forest, and called Iron John. "What dost thou desire?" asked he. "That I may catch the King's daughter's golden apple." "It is as safe as if thou hadst it already," said Iron John. "Thou shalt likewise have a suit of red armor for the occasion, and ride on a spirited chestnut horse." When the day came, the youth galloped to the spot, took his place amongst the knights, and was recognized by no one. The King's daughter came forward, and threw a golden apple to the knights, but none of them caught it but he, only as soon as he had it he galloped away.

On the second day Iron John equipped him as a white knight, and gave him a white horse. Again he was the only one who caught the apple, and he did not linger an instant, but galloped off with it. The King grew angry, and said, "That is not allowed; he must appear before me and tell his name." He gave the order that if the knight who caught the apple should go away again they should pursue him, and if he did not come back willingly, they were to cut him down and stab him.

On the third day, he received from Iron John a suit of black armor and a black horse, and again he caught the apple. But when he was riding off with it, the King's attendants pursued him, and one of them got so near him that he wounded the youth's leg with the point of his sword. The youth nevertheless escaped from them, but his horse leapt so violently that the helmet fell from the youth's head, and they could see that he had golden hair. They rode back and announced this to the King.

The following day the King's daughter asked the gardener about his boy. "He is at work in the garden; the queer creature has been at the festival too, and only came home yesterday evening; he has likewise shown my children three golden apples which he has won."

The King had him summoned into his presence, and he came and again had his little cap on his head. But the King's daughter went up to him and took it off, and then his golden hair fell down over his shoulders, and he was so handsome that all were amazed. "Art thou the knight who came every day to the festival, always in different colors, and who caught the three golden apples?" asked the King. "Yes," answered he, "and here the apples are," and he took them out of his pocket, and returned them to the King. "If thou desirest further proof, thou mayest see the wound which thy people gave me when they followed me. But I am likewise the knight who helped thee to thy victory over thine enemies." "If thou canst perform such deeds as that, thou art no gardener's boy; tell me, who is thy father?" "My father is a mighty King, and gold have I in plenty as great as I require." "I well see," said the King, "that I owe thanks to thee; can I do anything to please thee?" "Yes," answered he, "that indeed thou canst. Give me thy daughter to wife."

The maiden laughed, and said, "He does not stand much on ceremony, but I have already seen by his golden hair that he was no gardener's boy," and then she went and kissed him. His father and mother came to the wedding, and were in great delight, for they had given up all hope of ever seeing their dear son again. And as they were sitting at the marriage-feast, the music suddenly stopped, the doors opened, and a stately King came in with a great retinue. He went up to the youth, embraced him and said, "I am Iron John, and was by enchantment a wild man, but thou hast set me free; all the treasures which I possess, shall be thy property." - -

<< Home