The Faery Gleam of Fate

As I age, my first connections grow the more apparent and enduring, as if I spend my life waking from a dream. A sweet illimitable dream replete with buxom callipygean waves, crisp dangerous foam and plunging blueblack troughs.

Recently I’ve thought and versed much on the childhood scene of singing to Big Toad in a yellow plastic bucket when I was about three. We were vacationing at Cape Cod. At that time my parents were having a horrible time together -- my father had bleeding ulcers -- their marriage was wrong from the start -- yet my mother was pregnant with my sister and the beach air was uterally soft and distaff, mistral and serene. I captured a frog and made it the audience for songs that were in my head, or songs which the frog taught me. So there was darkness and light, both ephemeral, both essential. (That same vacation I fell from a bed during a nap and split my lip open; I still have a tiny white scar there.)

Katherine Briggs in The Fairies in Tradition and Literature relates the story of young boy (who later became a prominent lawyer) whose encounter with the fairies was wondrous, terrifying and fading:

***

This child, when he was a little boy of about four, lived in a big Manse, near the church, on one of the Islands. He was a solitary boy, they youngest of all his family, and he wandered about alone, or with the fishermen. One night as he was returning home he saw a great light in the church, and heard the sound of thousands of little musical bells. In a moment the church disappeared, and he saw nothing but a brilliant and many-coloured light. Then it turned to darkness, and the music to horrible and evil wailings. He was terrified and ran into the kitchen, where he told the cook what he had seen and heard. She comforted him, and told him he was lucky to have seen the fairies. After that he saw the same thing three or four times, but with diminishing vividness. The fear of the dreadful cries haunted him and he began to pine. But he was comforted by an old woman whom he trusted, and who told him that the wailing he heard was that of the bogies, who were being punished by the good fairies for their jealousy of him. The last time he had the vision was from the drawing room of the Manse. He saw the light and heard the music faintly, and then some deep sighs; and no more. So he knew that the fairies would not appear to him again.

THE SEA-BELLS

August 5

This hour is when my ear and mind

are youngest, hence freshest for

the sound of faery bells surfside

of here, a merry plash of darkling

thunder spilling blue moons over all.

You have to go freely into the veld

of the almost-woken day, like the

child who walked out of a cottage

by the sea and found a frog prince

in pine woods nearby, playing his

little tuba. There was a tiny gold key

on a chain hanging around

that toad neck which still unlocks

the doors of ocean, deep

inside the tidal heart of things

which washes out to reach

all shores, then ebbs slowly

back to here, like harrowed

blood from furthest limbs.

The music in that sea-works

is faint and frail, impossible

to hold on for long and

terrifying for what it implies:

Priceless here, like the

scattered gold of long-lost ships

still gleaming down there

where only moonlight reflected

in that frog’s eyes can reach.

That haunting fire goes dark

and dour then disappears

come first light’s certain wash

by which all children wake

and forget their nursery rhymes

and nightmares and thus

commence their growing up.

My song’s a bucket from that

old well, a yellow pail housing

that big toad who taught me how to

sing with the rudest of bull bassos

like a whale throned in a teacup,

sweet perfection’s curved

patinas inside the conch

of seas I’ll ever dream. Lord

keep me blind to that blue

now regent in the east

and enrapt with ancient

crashing shores. I keep

hauling new strings of

the sea’s old bells

long faded of blue

doors and keels and hells

yet sings and sails on here.

***

The contours of such singing emerge strangely, from a distaff reach which is faery and sublime. The way it sounds at first sounds different later on, perplex, more true. In a dream last night I was to appear on a late-night variety show (perfect metaphor for the dream); it was hosted by a childhood friend of mine, not specific, just a sense that I’ve known this guy a long time, and he had the look of a grownup childhood star, age a mere patina for old glories ... Anyway I was to play some of my current hit songs with a band, but as the hour approached (the show was live), I realized I had forgotten all the songs. Desperately I racked my brains for a fin of them, something to fish the wild rock sounds out -- I had the feeling they were gritty raw and bone-deep true -- but I came up with nothing. Show starts, my act comes up in ten minutes, and The Host sees me fidget. What the hell do I do? Grab an acoustic guitar and play the old old songs? With a crappy voice like mine, on national TV? Still nothing. Then it dawns on me that all that music went underground into the vatic enterprise, “singing” AKA versifying and prosaically perambling the salt keeps of the Deeparoo. Shall I suit up as Brendan and commence to recite my immrama? I wake at 1:10 a.m., surfaced from the dream in intense conflict.

What is it that we really bring forth? For some reason Rachel Carson gets at the task in this passage from The Sea Around Us, where she describes beautifully of the hidden mansions beneath the sea:

***

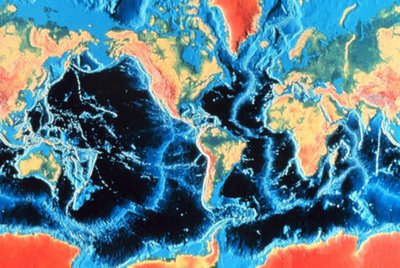

Unlike the scattered sea mounts, the long ranges of undersea mountains have been marked on the charts for a good many years. The Atlantic Ridge was discovered about a century ago. The early surveys for the rout of the trans-Atlantic cable gave the first hint of its existence. The German oceanographic vessel Meteor, which crossed and recrossed the Atlantic during the 1920’s, established the contours of much of the Ridge. The Atlantis of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has spent several summers in an exhaustive study of the ridge in the general vicinity of the Azores.

Now we can trace the outlines of this giant mountain range, and dimly we begin to see the details of its hidden peaks and valleys. The Ridge rises in mid-Atlantic near Iceland. From this far-northern latitude it runs south midway between the continents, crosses the equator into the South Atlantic, and continues to about 50 degrees south latitude, where it turns sharply eastward under the tip of Africa and runs toward the Indian Ocean. Its general course closely parallels the coastlines of the bordering continents, even to the definite flexure at the equator between the hump of Brazil and the eastward-curving coast of Africa. To some people this curvature has suggested that the Ridge was once a part of a great continental mass, left behind in mid-ocean when, according to one theory, the continents of North and South America drifted away from Europe and Africa. However, recent work shows that on the floor of the Atlantic there are thick masses of sediments which must have required hundreds of millions of years for their accumulation.

Throughout much of its 10,000-mile length, the Atlantic Ridge is a place of disturbed and uneasy movements of the ocean floor, and the whole Ridge gives the impression of something formed by the interplay of great, opposing forces. From its western hills across to where its slopes roll down into the eastern Atlantic basin, the range is about twice as wide as the Andes and several times the width of the Appalachians. Near the equator a deep gash cuts across it from east to west -- The Romanche Trench. This is the only point o f communication between the deep basins of the eastern and western Atlantic, although among its highest peaks there are other, lesser mountain passes.

The greater part of the Ridge is, of course, submerged. Its central backbone rises some 5,000 to 10,000 feet above the sea floor, but another mile of water lies above most of its summits. Yet here and there a peak thrusts itself up out of the darkness of deep water and pushes above the surface of the ocean. These are the islands of the Mid-Atlantic. The highest peak of the Ridge is Pico Island of the Azores. It rises 27,000 feet above the ocean floor, with only its upper 7,000 or 8,000 feet emergent. The sharpest peaks of the Ridge are the cluster of islets known as Rocks of St. Paul, near the equator. The entire cluster of half a dozen islets is not more than a quarter of a mile across, and their rocky slopes drop off at so sheer an angle that water more than half a mile deep lies only a few feet off shore. The sultry volcanic bulk of Ascension is another peak of the Atlantic Ridge; so are Tristan da Cunha, Gough, and Bouvet.

But most of the Ridge lies forever hidden from human eyes. Its contours have been made out only indirectly by the marvelous probings of sound waves; bits of its substance have been brought up to us by corers and dredges; and some details of its landscape have been photographed with deep-sea cameras. with these aids our imaginations can picture the grandeur of the undersea mountains, with their sheer cliffs and rocky terraces, their deep valleys and towering peaks. If we are to compare the ocean’s mountains with anything on the continents, we must think of terrestrial mountains far above the timber line, with their silent snow-filled valleys and their naked rocks swept by the winds. For the sea, too, has its inverted ‘timber line’ or plant line, below which no vegetation can grow. The slopes of the undersea mountains are far beyond the reach of the sun’s rays, an there are only bare rocks, and, in the valleys, the deep drifts of sediments that have been silently piling up through the millions upon millions of years.

***

An invisible immensity which is there though we know it hardly: such a presence supplies throat for me, what was in childhood a big toad and in adulthood a sounding whale, of the same tribe and Ridge, a totem of frightening depth and immensity and wonder, still captive in the confines of a bright plastic pail set beneath the wooing shade of a pine some distance from the sursurrant sea, neither close nor far. I bring you the news of that drowned land whose spine is the world’s, is mine, is yours.

<< Home