A Boy's Song

DOLPHIN BOY

1991

All the world's a whisper,

Where ocean margins cry,

I ride my fevered fishes there

Between the breakers and the sky.

Cities lie beneath the flood,

The sun king sleeps below.

But I croon darkly in your blood,

With brine and brawl and brogue.

A woman waits for you on a shore

No course you chart can reach.

Only storms can take you there

To wreck you on her beach.

I am the Dylan of your fathers,

Galloping the nine-wave brute,

I call you from your harbors

Into the darkness of all truth.

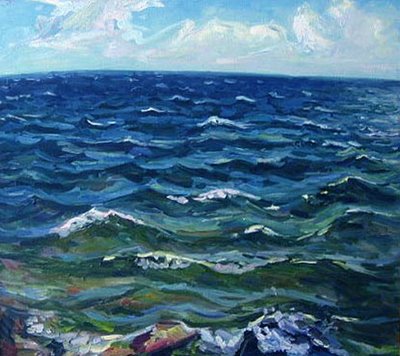

The mythic perspective -- which roots in ancient human experience and spreads its weird canopy in a cathedral arch over our daily acts and sears and soaring souring aspirations -- is one we can never adequately harrow, much less describe or name. It’s too deep, too wild, too strange, too ineffable. We can, as Campbell accomplished in his long career, succeed in quantifying the masks of God in a catalogue of sorts, but that’s as close as we get to enquiring the ghoul behind the eyeholes. Something icy and eternal stares back at us from the well’s bottom, from the resounding surf, from the infinite sky.

Yet we must try; that quest nails us with a passion which we can neither requite nor sustain, no matter how far we flee from it or engage with our most potent articulations. I venture that each of us has a daunting metaphor which we’ve ridden and formulated again and again since we were young.

In The Soul’s Code, James Hillman asserts that each of us is born with a nut of myth implanted deeply in our psyches: “Each person bears a uniqueness that asks to be lived and that is already present before it can be lived.” The call to my adventure was announced in the lietmotifs of my childhood: in my mother singing to me over the sound of the surf at Jacksonville Beach, in the songs I made up singing to Big Toad whom I kept in a plastic pail, in the nightmare of the civil war outside my grade school where I had first enquired into the nature of what hides beneath girls’ bloomers, in the figure of my father up at the front of the church where he intoned his sermons, in the apocalyptic battles with big lugs who were always whupping my ass but good. Out of those events -- delicious wounds of nurture -- my nature slowly emerged, weirdly fused with those events, deep and strong because and despite the pain I suffered. I sought God in heaven and brassieres and bottles and guitars and crashing waves and poems and the bottoms of wells and abysms plunged by whales along a road whose ley was too meandering, too daunting to understand, much less name, ever more especially so every day.

The quest that has surfaced or been excavated down all these years is impossible -- like stealing treasure from a dragon -- but for that it becomes primary, essential, a bass note resonating under and through all the ways I have along the way mortared and planted myself into the surface world, in marriage and career. While I find myself ever more astride a bland tide of dailiness with its undertow of loss and susurrant ebbing waves, I have at the same time fought for and found a difficult and conditional shore where the quest continues. I’ve grown more serious about the quest as I’ve aged, my personas have morphed through the court cards, page to knight to king of salted sacred space, which for me has become a rock-solid liturgical matin a few hours in the dead of night before the day begins.

There has been a cost, but the very dearness of it has lent validity to the quest, a validity which only gods can proffer and one which is nigh-invisible in the light of day. I’ve lost years of sleep and wasted oceans of ink in this quest. Many times I’ve doubted the enterprise, the dogged drone of it; at those times the quest seems silly and moot. Whatever ends I once dreamed it might bring -- booty, fame, bigger digs inside the soul’s keep -- have come to naught, at least in the ways I imagined. The best I’ve come to understand of this is that the daily framing and farming and flinting and flinging of the mystery itself pays invisible dividends, ones which can’t be harvested until one knows absolutely that they have no cash value and are of no interest to the dayside world at all. That’s the Otherworld deal: fantastic sums which turn to dust at the cashier’s window.

I have my favorite stories, myths which I’ve found along the way which especially resonate with this quest and may indeed be the underworld face looking up at me from all the masks and tropes I’ve fashioned. I love the tale of St. Oran’s travel to the North when he is buried in the footers of the Iona Abbey, down and out in search of the sea god who once had inhabited that isle and fled with the coming of Christianity; Oran travels island to island in search of this god, each time encountering a sign which says “Not Here.” It is a sign of presence at the same time invoking absence, a way of eternally renewing the quest, bidding Oran to sail toward the next shore while at the same time telling us that the searched-for numen is always near but not in any visible way.

I also like the tale of St. Brendan’s voyage, which he undertakes in penance for his burning a book of God’s wonders which he had deemed untrue. His amends is to sail the islands of wonder with his monks and experience what was margined in that lost book, and then, at some far point, return to Ireland, write down what he had seen, and offer the refilled-book at an altar dedicated to Mary, Queen of Heaven.

Along the way he encounters birds of paradise fallen from heaven, the leviathan Jasconius with his tail inside its mouth (on whose back he will celebrate the Easter mass for seven years), a devouring devil cat and a crystal tower in the middle of the sea. All are sights of awe and awesomeness, and each seems like an end -- how could any wonder be greater? Yet each invokes another chapter of the Voyage. Is that not how we quest, too, the mystery growing wider and wilder as we query the phantasms of deep dream and read the mystery texts like the physiognomy of a Sphinx, the details filling in a visage which grows weirdly identical to the one we first found in childhood?

Hillman -- to me one of the great captains of the underworld voyage, articulating motions of psyche which are ever at quest -- turns the notion of growing up on its head, stating it is not up but down that we grow:

***

“To be an adult is to be a grown-up. Yet this is merely one way of speaking of maturity, and a heroic one at that. For even tomato plants and the tallest trees send down roots as they rise toward the light. Yet the metaphors for our lives see mainly the upward part of organic motion.

“Hasn’t something critical been omitted in the ascensionist model? Birthing. Normally we come into the world headfirst, like divers into the pool of humanity. Besides, the head has a soft spot through which the infant soul, according to the traditions of body symbolism, could still be influenced by its origins. The slow closing of the head’s fontanel and fissures, its hardening into a tightly sealed skull, signified separation from an invisible beyond and final arrival here. Descent takes a while. We grow down, and we need a long life to get our feet.”

***

Finding our feet: what a mythic tale washes round that theme, a tale tale deeper than the Flood! When Jesus washes the feet of his disciples, is he baptising us in the oldest mystery of all, that of walking up out of the sea and standing alone on bleached white shores? Does our story go back that far? Is our own story, which begins with the first gleams of consciousness up out of a watery mist -- the recollection of a pattern of sunlight on a carpet, the sound of parent’s voice, the softness of a crib with some enormity of space beyond reach -- are such memories metonymic of the oceanic story of life?

If so, then heavens, how could we ever hope to fully write such a tale? Easier to measure the wet part of the sea. “Unsagbareitstropos” is the rhetorical formula used by authors to explain they cannot record everything they should like to write down; the little man on the leaf on the sea who attempts to measure it out, bowl after bowl, is a metaphor for the task facing Brendan, who has been bidden by God to fill a book of wonders with the keel of a coracle which then becomes the nib of a pen. But try he must; and the plenitude of St. Brendan tales in the literature to me tells us that his work is essentially our own, a voyage back to sources, to the treasure hardest to attain.

There’s a child at the end of our deep questing, the one we grew up from and then slowly grew back down into, along all the years of our attempts to measure out the great sea inside us, bowl after futile bowl (or, in my voyage, Bible after bottle after brassiere after guitar after pen). Our end is his beginning, the one laughing and smiling up at the pure undifferentiated world as mother, the whole of it smiling its imprint in the words we will later come to say, no matter how futile and short and shrunken they seem.

BOY SONG

Today

What I write here sails

the words I heard my

mother sing over the

choiring sea nearing

50 years ago. These lines

are rigged in boats

which leapt out

from my chest

when I sang my first

songs back to Big Toad,

the Frog In The Pail

(capitals required here

for a remembered

child’s archons).

Those first songs

rudder these later

ones toward every shore

I heard back then

in my mother’s

the curved sea’s voice,

whose tide and timbre

my songs baptize,

wave after love after poem.

Sometimes it’s just a drone,

as bland and brutally

compulsive as the ostinato

surf which has played

one salt melody for nigh

three billion years; yet

even such dull similitude

delves gold doubloons,

its tidy rhythmus fleet

for daily pannings of the tide,

like pious rosaries of

wild blue. The man that

child became is

both sire and son

of siren song, a welcome

grown cathedral in an

aging man’s lowered voice;

one tutored in the mother

tongue enough to whale

back its gaelic brogue

with all the tang and blister

of the seal-man Angus

who satirized the white priest’s

mastery over exiled seas.

Against all learned brilliance

I go back to that boy’s

whispered pre-tonal tune,

so faint and moot that

you’d surely miss it mid

the clatter of a normal

family’s day, & with the

sea not far away

murmuring grey swooshes

over that boy’s ride

in the rolling heart of God.

His first song is my last

as of this next writing day,

an old bell hauled up from

ocean beds & the wombs

every love I lost & all

those bottles that I emptied

searching for what the

booze so blithely tossed.

His bell’s inside my voice,

a clarion ring of a spout

of a careening wave

of a keel of a flout of

proud jissoming stout

empurpled ding-dong song

which praises Gop in

an angel monkey’s brogue,

clabbering His bell

the way a tongue

hits on the hidden blue

surfaces below of the shore

that first boy’s first song

dreamed. It was just

a heartfelt ditty

on a day forever lost,

a pale small seed tossed

back in the surf

which down the years

grew into this loud

organum of five

times fifty seas,

a music that I’ll forever

shore, whose strange

old ligature I scrawl

in screaming jots of

spermaceti oil on

ink-black mornings here.

On a simple day

I sat beneath a fragrant

pine with a straw

heat on my head,

strumming with

no art upon a toy guitar

& peering in that yellow

pail at low toad, the

diplomat from every

slimy wild nook. I

sang exactly what

I heard the sea croon

not far away in

what seemed my

mother’s voice, and

I sang back, repeating

what I somehow knew

was most my own.

That boy of my first

history is the Hermes

of this soak which

only bears the title

of “poetry” but is something

far older, as that boy

upon the beach taught

the sea itself to sing.

This soak of voice of

words on paper boats

no real tide will float,

much less ferry, is

the theme I womb.

I sing of tide-crashing seas

and they sing back

the shores of mystery,

a bed where my Beloved sings

from God’s depths the

sea’s salt history.

BOY ON A DOLPHIN

2005

He is forever young astride

that sleek so wild blue dolphin,

yeehawing over the foaming

waves or dead asleep -- enwombed

still in first bliss -- or perhaps

even dead, ferried homeward

on Thalassa’s hearse. In all

the flower tucked behind

his ear bespeaks a listening

which trumpets back in

the antiphons of full bloom,

hurling such perfume

that the entire sea swoons

enrapt, sending curve

after curve his way

to plunge and riot

and plow under to

the source where all

life begins. No wonder

he appeared on so many

ancient coins -- the poster

boy for fortune’s pluck,

the gilded lucre through

which old men get

maids to fuck,

a way to duck death’s

swash by minting back

the eyes with youth.

Always a sea and shore

between his romp,

as he and fish are

merged in the marge

of tidal marches which

pulse a God’s blue

augments as they crash

and ebb the heart:

Always a fish-tail for

ship’s rudder, a song

for wet travail, a course

both known and

abyssal toward ends

both gold and bone.

And though the visage

of this tale is young

-- both boy and fish

careen in puppy glee --

it masks a far far

older man’s dark face,

that brooder

of the first horrific

sea, bull-ravager of

Europa, the wolfish

sharps and flats of

Apollo’s golden lyre

keyed from Hypoborean

depths. That old man is

Uranos, cleft of his

huge balls, dreaming

Aphrodite from the

froth of that first wound:

He’s the ghost of the

singer Arion, doomed to sing

to a court of whale-

and ship-ribs

two hundred leagues

below the wake he

was ditched by pirates in,

singing of rescue

to dry shores by the

dolphin not found

outside of songs:

He is Poseidon

inside his stallion

hooves which you

hear bestride the waves’

stampede to shore, a

thunder which grows

loud the more both sea

and land agree to share the

augments of a strand’s

so liquid rocky roar.

Behind or under that

puerile sweet of song’s first

crash and plunge

wakes first man of the sea,

a giant walking just beneath

the boy we care to see.

The boy astride the dolphin

crests so much that’s far

under me, ruddering his

courses in this hand which

writes his emblem down.

<< Home