The Copyist

COPYIST

2004

A reader is a writer

moved to emulation.

-- Saul Bellow

Each day I write down lines I find

In books which sound of Oran, a

Blue lucence which old words retain.

The words sail to me from him, or

God, or some deep resonance I’ve

Yet to find apt name. Copying

Is both rigorous and charmed: these

Migraines are the cost of years of

Writing down so much high angelic

Song -- And yet I bear those sharp hooves

Gladly on my skull, for birth is

Always red and wild. Today I

Copied the last lines of a saint’s

Life -- a plea and a prayer to copy well.

That done, I write down blue hell.

Some turbidity awakened a few days back in the middle aether between home and star, fomenting clouds and, blessedly, storms which blow hard and rain long. We missed the first front on Tuesday night (much staccato brilliance of bluewhite lightning to the south, the faintest ebbs of a rumbling surf). Yesterday the edges of storm again ran out somewhere north of Apopka, leaving us to think we would go wet-supperless again. But as we ate dinner watching “The Daily Show” the dark outside began to writhe, and blow, and then spume rain in every direction, a torrent which our dry garden must have received like a parched lover, crying Yes and More to her demon gallant’s unleashing. Hosannah and amen.

It was a night for gratitude, my wife delivering her first custom job to the utter delight of her client, a second job immediately referred; me with no migraine for the day, feeling exquisite delight for simple normalcy; Violet getting a snootful of premium tuna fish from the cans my wife opened while preparing our dinner of stuffed tomatoes. (Our little girl pacing in the kitchen, mewling with urgency, huge Siamese fangs exposed in her crosseyed cries.)

All of us graced in what counts in the daily score, none of it ever more than occasional yet in such congress together is a pure gift, a divine shore, and balmed us all in sweet sleep. So what if I wake with a fresh migraine steeling up my neck, when there is good work to do and the early morning blows fresh through the windows, repleted as we, ready to begin ...

Picking up from Neumann’s chapter “The Balance and Crisis of Consciousness” in his book The Origins and History of Consciousness, let’s delve into the cultural substratum of a world in which creativity oversteps itself, challenging the law of cultural paternity on the outside and effectively bridging into primal chaos on the inside:

***

... the hero, like the ego, stands between two worlds: the inner world that threatens to overwhelm him, and the outer world that wants to liquidate him for breaking the old laws. Only the hero can stand his ground against these collective forces, because he is the exemplar of individuality and possess the light of consciousness.

Notwithstanding its original hostility the collective later accepts the hero into its pantheon, and his creative quality lives on--at least in the Western canon--as a value. The paradox that the breaker of the old canon is incorporated into the canon itself is typical of the creative character of Western consciousness whose special position we have repeatedly stressed. The tradition in which the ego is brought up demands emulation of the hero in so far as he has created the canon of current values. That is to say, consciousness, moral responsibility, freedom, etc., count as the supreme good. The individual is educated up to them, but woe to any who dares flout the cultural values, for he will instantly be outlawed by the collective as the breaker of the old tablets.

Only the hero can destroy the old and extricate himself from the toils of his culture by a creative assault upon it, but normally its compensatory structure must be preserved at all costs by the collective. Its resistance to the hero and its expulsion of him are justifiable as a defense against immanent collapse. For a collapse such as the innovations of the Great Individual bring with them is a portentous event for millions of people. When an old cultural canon is demolished, there follows a period of chaos and destruction which may last for centuries, and in which hecatombs of victims are sacrificed until a new, stable canon is established, with a compensatory structure strong enough to guarantee a modicum of security to the collective and the individual.

***

So culture is a yolky pleroma in which our blisses gestate, commanding our gestalts, oaring our adventuring minds into the next room of the dream. It is the prima materia of imagination, its salt sea, its umbilicus into the realm of chaos and foment and endlessly wicked delight. The articulation of any creative work is a head which has been doused in that wave, like a baptism, and rises, ah, dripping with unknowns (I keep stealing that image from Rilke’s Third Elegy). And, thus whet on the tempering stone of abyss, the articulation strikes a clean thrust at the sky, arrogant and proud and daring and cruel, swiping off the balls of the father and gate-keeper of the divine mother’s sacred bower. We con a way back into that vault that we may plunge and succor its sweetness without restraint. Every articulation an assault on the past which both deepens and furthers the pleroma.

***

This time seems to have the resonance of a corrupt cultural canon; if anything we are adrift and befogged in the white noise of technology, and the old cultural commodities of reading and singing and painting all seem bankrupt, sterile, drowning in that white tide. The academies are productive for the sciences but are mere degree mills for the arts, churning out literate PhDs with no hope for tenure and a combative rhetoric which no real ties to a canon, that canon having dessicated to dust by modernity and pluralism.

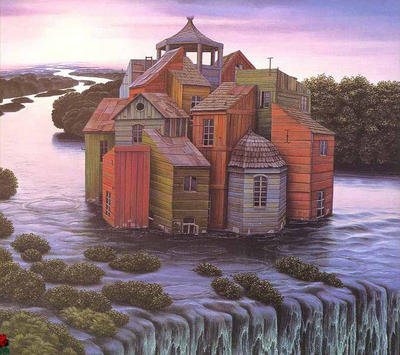

Ah but this is boring, ain’t it? The mere sound of my voice here is tired, a drone. All of this is so known as to grow rote. It is the tenor of exhaustion, is sown into the tenor of cultural wasteland, haunts the dread centuries which interface old and new canons. Like they say in AA, “‘Why’ is not important”; suffice that we can either hang out on the crumbling bridge of the drowned Titanic, ideating icebergs and arrogance large enough to sink a world, or we get out of the icy water somehow and hitch a ride on whatever floating ships are in the vicinity.

These posts -- dark confections of prose and poetry, history and mystery, sexual whiskey and diviner nipplage -- are coracles of that diaspora, trusting the deeper older sources to rudder the song on to those eventual shores where abbeys survive their offending footers and the hecatombs of futurity get written down.

The ley lines of such a work can be traced from a far older work -- surely by now you know where I look -- observe carefully how a futurity was constructed in the Dark Ages. This from Thomas Cahill’s How The Irish Saved Civilization

The Irish received literacy in their own way, as something to play with. The only alphabet they’d ever known was prehistoric Ogham, a cumbersome set of lines based on the Roman alphabet, which they incised laboriously into the corners of standing stones to turn them into memorials. These runelike inscriptions, which continued to appear in the early years of the Christian period, hardly suggested what would happen next, for within a generation the Irish had mastered Latin and even Greek and, as best they could, were picking up some Hebrew. As we have seen already, they devised Irish grammars, and copied out the whole of their native oral literature. All this was fairly straightforward, too straightforward once they’d got the hang of it. They began to make up languages. The members of a far-flung secret society, formed as early as the late fifth century (barely a generation after the Irish had become literate), could write to one another in impenetrably erudite, neverbefore-spoken patterns of Latin, called Hisperica Famina, not unlike the dream-language of “Finnegans Wake” or even the languages J. R. R. Tolkien would one day make up for his hobbits and elves.

Nothing brought out Irish playfulness more than the copying of the books themselves, a task no reader of the ancient world could entirely neglect. At the outset there were in Ireland no scriptoria to speak of, just individual hermits and monks, each in his little beehive cell or sitting outside in fine weather, copying a needed text from a borrowed book, old book on one knee, fresh sheepskin pages on the other. Even at their grandest, these were simple, out-of-doors people. (As late as the ninth century an Irish annotator describes himself as writing under a greenwood tree while listening to a clearvoiced cuckoo hopping from bush to bush.)

But they found the shapes of letters magical. Why, they asked themselves, did a B look the way it did? Could it look some other way? Was there an essential B-ness? The result of such why-is-the-skyblue questions was a new kind of book, the Irish codex; and one after another, Ireland began to produce the most spectacular, magical books the world had ever seen.

From its earliest manifestations literacy had a decorative aspect. How could it be otherwise, since implicit in all pictograms, hieroglyphs, and letters is some cultural esthetic, some answer to the question, What is most beautiful? The Mesoamerican answer lies in looped and bulbous rock carvings, the Chinese answer in vibrantly minimalist brush strokes, the ancient Egyptian answer in stately picture puzzles. Even alphabets, those most abstract and frozen forms of communication, embody an esthetic, which changes depending on the culture of its user. How unlike one another the carved, unyielding Roman alphabet of Augustus’s triumphal arches and the idiosyncratically homely Romano-Germanic alphabet of Gutenberg’s Bible.

For their part, the Irish combined the stately letters of the Greek and Roman alphabets with the talismanic, spellbinding simplicity of Ogham to produce initial capitals and headings that rivet one’s eyes to the page and hold the reader in awe. As late as the twelfth century, Geraldus Cambrensis was forced to conclude that the Book of Kells was “the work of an angel, not of a man.” Even today, Nicolete Gray in A History of Lettering can say of its great “Chi-Rho” page that the three Greek characters-the monogram of Christ-are “more presences than letters. “

For the body of the text, the Irish developed two hands, one a dignified but rounded script called Irish half-uncial, the other an easy-to-write script called Irish minuscule that was more readable, more fluid, and, well, happier than anything devised by the Romans. Recommended by its ease and readability, this second hand would be adopted by a great many scribes far beyond the borders of Ireland, becoming the common script of the Middle Ages.

As decoration for the texts of their most precious books, the Irish instinctively found their models not in the crude lines of Ogham, but in their own prehistoric mathematics and their own most ancient evidence of the human spirit-the megalithic tombs of the Boyne Valley. These tombs had been constructed in Ireland about 3000 B.C. in the same eon that Stonehenge was built in Britain. just as mysterious as Stonehenge, both for their provenance and the complexity of their engineering, these great barrow graves are Ireland’s earliest architecture and are faced by the indecipherable spirals, zigzags, and lozenges of Ireland’s earliest art. These massive tumuli, telling a story we can now only speculate on,” had long provided Irish smiths with their artistic inspiration. For in the sweeping lines of the Boyne’s intriguing carvings, we can discern the ultimate sources of the magnificent metal jewelry and other objects that were being made at the outset of the Patrician period by smiths who, in Irish society, had the status of seers.

Brooches, boxes, discs, scabbards, clips, and horse trappings of the time all proclaim their devotion to the models of the Boyne Valley carvings. But this intricate riot of metalwork, allowing for subtleties impossible in stone, is like a series of riffs on the original theme. What was that theme? Balance in imbalance. Take, for instance, the witty cover on the bronze box that is part of the Somerset Hoard from Galway: precisely mathematical yet deliberately (one might almost say perversely) off-center, forged by a smith of expert compass and twinkling eye. It is endlessly fascinating because, as a riff on circularity, it has no end. It seems to say, with the spirals of Newgrange, “There is no circle; there is only the spiral, the endlessly reconfigurable spiral. There are no straight lines, only curved ones.” Or, to recall the most characteristic of all Irish responses when faced with the demand for a plain, unequivocal answer: “Well, it is, and it isn’t.” “She does, and she doesn’t.” “You will, and you won’t. “

This sense of balance in imbalance, of riotous complexity moving swiftly within a basic unity, would now find its most extravagant expression in Irish Christian art-in the monumental high crosses, in miraculous liturgical vessels such as the Ardagh Chalice, and, most delicately of all, in the art of the Irish codex.

“Codex” was used originally to distinguish a book, as we know it today, from its ancestor, the scroll. By Patrick’s time the codex had almost universally displaced the scroll, because a codex was so much easier to dip into and peruse than a cumbersome scroll, which had the distinct disadvantage of snapping back into a roll the moment one became too absorbed in the text. The pages of most books were of mottled parchment, that is, dried sheepskin, which was universally available—and nowhere more abundant than in Ireland, whose bright green fields still host each April an explosion of new white lambs. Vellum, or calfskin, which was more uniformly white when dried, was used more sparingly for the most honored texts. (The “white Gospel page” of “The Hermit’s Song” is undoubtedly vellum.) It is interesting to consider that the shape of the modern book, taller than wide, was determined by the dimensions of a sheepskin, which could most economically be cut into double pages that yield our modern book shape when folded. The scribe transcribed the text onto pages gathered into a booklet called a quire, later stitched with other quires into a larger volume, which was then sometimes bound between protecting covers. Books and pamphlets of less consequence were often left unbound. Thus, a form of the “cheap paperback” was known even in the fifth century.

The most famous Irish codex is the Book of Kells, kept in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, but dozens of others survive, their names-the Book of Echternach, for instance, or the Book of Maihingen—sometimes giving us an idea of how far they traveled from the Irish scriptoria that were their primeval source. Astonishingly decorated Irish manuscripts of the early medieval period are today the great jewels of libraries in England, France, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Italy, and even Russia.

(pp 164-169)

***

BLACK KELLS

2003

A page torn from the

night’s black book

of Kells, drunk at some

music club a lifetime ago

& chasing a fattish

Icelandic gal, whose

eyes were blue as blindness:

Pawned angels dance

to phat jazz, their huge

black wings scraping

the backs of deacons

who stand at the bar

pounding back their

wasted genius, work and lust

in tiny shots of Jaegermeister.

Down down down

burns the the

black fuse of white

thirst no poured

heaven can allay

or alloy, minting

balled fists of

desire unclinched

nowhere, not even

in the grave.

Even the eventual

bed is a fraud,

apportioned from

a business-class

hotel close to

downtown, adrift

in the deep a.m.’s

of blackout, TV,

and sex, cold and nearly

sick, the slick inches

narrowed & grit

& flubbed then

jawed whole. Cho Ri

page of my demon

gospel, face of the

Savior inverted,

limed, or drowned,

the glow too far

to swim safely to,

too faintly red

to matter,

the last bubbles

drifting up past her

ice blue eyes

fixed over my

shoulder at what

passed back then

for day, out toward

the esplanade where

children riffle

crack vials & a

wind blows

your last dream away.

Not all pages

of Kells were saved:

Two gospel title

pages are hidden

still, or lost,

evangels of a night

there is no ink

dark enough to

write & jaws

the copyist entire.

TITANIC

2002

Lave a whale a while

in a whillbarrow ... to

have fins and flippers

that shimmy and shake.

— James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

You say you egressed

here through the best

poems, but rather

you’ve sunk here

reaching for the

starlingest gleam

of stellarmost truth.

Your best descends

like a fat Bismarck

three miles down

to a cold grave.

It fails even to

fin that chill absence

at the bottom of the blue.

But what did you expect,

singing there on the

beach? Did you think

she could actually

return to you there,

stepping from some wave?

All that’s just a door

into this salt cellar

of dark savagery.

From her narrow waist

these whale roads where

the music of what falls

is what her smile calls.

SCRINIUM

2004

The word scrinium denotes in

classical Latin a letter-case or

book box, or any chest in which

papers are kept ... More generally,

scrinium was a synonym for

thesaurus or fiscus, the treasury

or mint, but in Christian usage

it seems to have been associated

with the keeping of all valuable

ecclesiastical items, including

records, books, and relics --

things for remembering.

-- Mary Carruthers, The Book of Memory

God made this world from

a word, but I compose

my words from the world

He vaults in me.

My song is a box walled

of unquiet wings and piercing

beams, the nuclear heat

which burns like a wilderness

around every singular

image -- cat in the window,

woman sewing in lamplight,

a trailer crushed beneath

the sprawled mass

of a southern oak. I press

those leaves here, each fallen

from some angel, a relic

handprint of gold or gules,

nails of the invisible

furrowing a road in

my palm. My wife

came back from her shop

yesterday looking whipped,

the downtown district of

Sanford torn up in

some developer’s dream

of better bigger bucks

than what the antique malls

and sandwich shops

provide, keeping all the

customers away from the

place she hopes to launch

her next better

commercial dream. She’s

been happier these past

few weeks than she’s been in

years, sewing her sheets

full-time, stitching her days

together into a fabric she

swears is worth the world.

What to say to her last night

as she placed earrings back

into the gauzy order of

our upstairs bedroom, the

late afternoon looking stormy

yet tided over, no rain for

the garden tonight, no real

evidence that yet she’ll ever turn

a real buck at this -- Violet

our cat on a bench at the

foot of the bed, half-addled

by our weary talk, one paw

extended, a gesture we construe as

contentment. Nothing really

to say to her but you just

keep working on the sheets

and take a turn with her

petting Violet, praising

her simple soft demure

perfection, finding physic

in that touch, as if that cat

warded the gates to brilliant

chambers down below

where every anguish nightly

goes and is washed three times

in some deep blue well

and is returned to us the next

day, freshened for next day’s labors,

this craft of cobbling a Paradise

from strewn leaves and stray gleams,

the camphor-balm of similes

we take as God’s smile here.

I will set each day here

as worthy of the till, the telling,

the gold fragments in that dirt

the sudden spill of what pours

from God’s pocket heavens,

his crashing, cashiering wave,

risen amid difficulty and

weariness, tangled in the

world’s broken sum,

and set the mint of

such gleams of bliss like

a coin on my eyes

and pay my passage back.

<< Home