Orphic Bling: Pynchon and Rilke

Ranier Maria Rilke and Thomas Pynchon are, in my humbled opinion (IMHO), two of creative mythology’s latter-day saints -- word-slakers and world-makers, arch-angelic hallowers and harrowers. Miners of that grand blue bling.

As I said yesterday, Gravity’s Rainbow was my Book of the Dead, the only book I read in the depths of my non-literate circuit through the Big Night Music. His voice like a soundtrack or a noir narrator to whatever the angels had to do with me in the years I was strapped to an electric guitar.

Rilke is the angel who came after that, when I gave up the world out there for the bell tower and well and ocean within. As I found my prose in Pynchon, so I found my verse in Rilke. Such self-recognition in great works I think is the mojo of literature, the liturgy of creative mythology: the travail of one is the rappel of another into long-forgotten Lascauxes.

Since Pynchon’s been in my thoughts of late as some sort of postmodern ringer of hallow solstice bells, I reprint here a paper I wrote in ‘93 about the influence of Rilke’s verse on Pynchon’s prose. Maybe I was then mapping back my affinities, lighting candles in whatever perplex cathedral the two of them share, neither the one or the other. Anyhoo, I wrote it in two weeks for a class, the effort totally out of proportion to the assignment but far insufficient for the theme, one which I continue to ring here.

***

“A Face on Ev’ry Mountainside, A Soul in Ev’ry Stone”: Rilke’s Poetics of Transformation in Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow

May 3, 1993

I. Introduction

Critics have commented on Thomas Pynchon’s use of Rilke in Gravity’s Rainbow (hereafter, GR). Josephine Hendin writes, “Pynchon plays Beethoven to Rilke’s Schubert, developing from Rilke’s encapsulated emotional statements operative definitions about the nature of science, thought and civilization” (50). Douglas Fowler is even more emphatic, placing Rilke at ground zero of Pynchon’s most difficult themes:

GR is saturated with references to Rilke and lines from his poetry, and it seems important in understanding Pynchon’s magic world to point out that, of all poems of any worth, Rilke’s are the most difficult either to describe or paraphrase, but that we can at least be certain they imply everywhere the overwhelming desire to drive beyond this life, these realities, this contemptible moment. The Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus begin several inches off the ground and then immediately fly off toward the same Transforming, Transcending Kingdom of Beyond that Pynchon can’t describe, either... (“Pynchon’s Magic World,” 59)

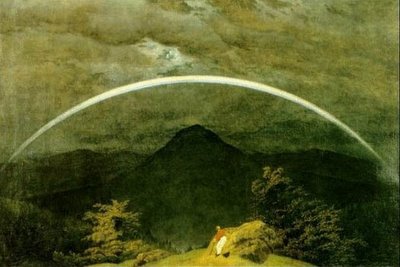

This is not to say that GR is about Rilke. Far from it: the novel is so complex and encompassing that any singular reading will fail. But I agree that Pynchon’s rainbow inherits some of its spectra from Rilke, particularly the poet’s theme of transformation. Two of the novel’s main protagonists, Weissman and Slothrop, personify Rilke’s search for transformation in the Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus. Transformation is one of many themes in the novel consistent with the rising and falling metaphor of the rainbow. Pynchon draws upon the hope of the Elegies to fire into the sky the longing to transform love in death; at the same time, in affirmation of the Sonnets, he brings God tumbling to Humility, scattering grace through the world.

In Weissman and Slothrop, transformation is both sublime and terrifying. Pynchon’s “heroes” are a sadomasochistic rocket commander and a hopelessly conditioned rube who suffers schizophrenia. Understandably, some critics focus on the darker aspects of these characters’ transformation and conclude that Pynchon uses Rilke only ironically. Others see Pynchon making a revolutionary affirmation of him.

Does Pynchon affirm or rebuke Rilke’s difficult vision? There are no sure answers. Rilke’s gone Beyond, Pynchon only speaks through his text (his anonymity is legendary), and GR is so purposely ambivalent that its answers are always a precarious todder between yes and no. Even so, Pynchon tilts his cards at moments, and they are sufficiently charged to show that he, too, had the courage to affirm the profound and dangerous rainbow of transformation.

II. Summary of the Texts

Rilke: Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus

Rilke brought together in his Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus something he had been trying to articulate for decades. In a letter he explained what the two works achieved:

... more and more in my life and in my work I am guided by the effort to correct our old repressions, which have removed and gradually estranged us from the mysteries out of whose abundance our lives might become truly infinite. It is true that these mysteries are dreadful, and people have always drawn away from them. But where can we find anything sweet and glorious that would never wear this mask, the mask of the dreadful? Life — and we know nothing else — , isn’t life itself dreadful? ... Whoever does not, sometime or other, give his full consent, his full joyous consent to the dreadfulness of life, can never take possession of the unutterable abundance and power of our existence; ...To show the identity of dreadfulness and bliss, those two faces on the same divine head, indeed this one single face, which just presents itself this way or that, according to our distance from it or state of mind in which we perceive it — : this is the true significance and purpose of the Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus. (Mitchell, Selected Poetry of Rilke, 317; italics are Rilke’s)

Rilke wrote the first three Elegies in 1912 but was aware they were part of a larger canvas he couldn’t yet elaborate. A decade passed while the poet struggled for a way to soar to their conclusion. The Great War raged and ravaged, and the poet wandered through the cities of Europe. Eventually Rilke settled at the little tower of Muzot in the Swiss Alps. During February 1921 he disappeared into “a hurricane of the spirit.” The poet stayed up in his room in the tower for days and nights at a time, pacing back and forth, “howling unbelievably vast commands and receiving signals from cosmic space and booming out to them my immense salvos of welcome” (Mitchell, Sonnets to Orpheus, 8). He wrote the remaining Elegies with such clarity they required almost no revision.

In the Elegies, Rilke beckons to the Angels who have mastered transformation into the realm of the invisible, even though he knows they have no need for him.

Who, if I cried, would hear me among the angelic

orders? And even if one of them suddenly

pressed me against his heart, I should fade in the strength of his

stronger existence. For Beauty’s nothing

but the beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear,

and why we adore it so is because it serenely

disdains to destroy us. Each single angel is terrible.

(First Elegy, transl. Leishman and Spender, 1-7)

The realm of angels is both absent of desire and is the ultimate fulfillment of desire. Angels are “terrible” to us because humans still “cling to the visible.” Fear of death prevents us from the godlike calm of angels; and were we to lose that fear and celebrate death, we might stop hating life’s limits. The Elegies range thematically from the contrast between angels and men, the transitory nature of human life, and the role of lovers, the early dead and the Hero in the hidden unity of life and death. The poems move with great fluidity, change perspective and focus in a heartbeat, and span great distances. “They are the nearest thing in the writing of the twentieth century to the flight of birds,” comments Robert Haas (xxxvi).

With these massive Elegies also came an torrent of smaller poems — 64 sonnets — which the poet dedicated to Orpheus, the primal poet richly storied in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The Sonnets sprang from the Elegies but have a different sound; in them we hear the pulse of life. The Sonnets rescued Rilke from suffocating in the vacuum of the Angels. Haas writes,

Through Orpheus, Rilke has suddenly seen a way to hack at the taproot of yearning and projection that produced the angels. It is a phenomenal moment, for announcing, as Nietzsche did, that God is dead is one thing — this was, after all, a relief, no more patriarch, no more ultimate explanation, which never made any sense in the first place, of human suffering — but to take the sense of abandonment which follows from that announcement, and the whole European spiritual tradition on which it was based, inside oneself and transform it there, is another. For once the angel is gone, once it ceases to exist as a primary term of comparison by which all human life is found wanting, then life itself becomes the measure and source of value, and the task of poetry is not god-making, but the creation and affirmation of the world. (xxxix)

Rilke’s Orpheus belongs to Nature, and his song is the passionate music of life. This is the mortal poet; though his song enchants the shades below, he cannot rescue Eurydice from death. Rising from death without her, utterly alone, Orpheus discovers in her death his own transformation; he finds a way to affirm both her death and his life. This Orpheus stands somewhere between immanent Apollo — one of his epithets is “He who shoots from afar” — and emanant Dionysos, mad god of the rapturous Now. Vibrating between the two, Orpheus is the music of “pure tension” (Sonnet 1.12, transl. Norton). This is astonishing praise, for the double realm of death-in-life spreads grace throughout the world.

Praising is what matters! He was summoned for that,

and came to us like the ore from a stone’s

silence. His mortal heart presses out

a deathless, inexhaustible wine.

Whenever he feels the god’s paradigm grip

his throat, the voice does not die in his mouth.

All becomes vineyard, all becomes grape,

ripened on the hills of his sensuous South.

Neither decay in the sepulcher of kings

nor any shadow that has fallen from the gods

can ever detract from his glorious praising. . . .

(Sonnet 1.7, transl. Mitchell)

Pynchon: Gravity’s Rainbow

Gravity’s Rainbow is nearly impossible to accurately summarize. Its seven hundred and fifty pages are a mad and frothy jumble of gritty war scenes, lowbrow B-movie escapades, lyric descriptions of pastoral Europe, sophomoric college songs, pornographic asides, sad farewells to century’s monolithic dead, ethnic theologies and agonizingly obtuse technical chatter. The book would evaporate of so many entropies were it not that each in their way accomplish a near but never complete transformation into something Pynchon never clearly states. Pynchon’s rainbow is mortared with a purposeful ambiguity where every action, character, scene and denouement is countered by an opposite both internal (meaning, no one thing means just one thing) and external.

Ambiguity is textured by randomness: forget about any sequential evolution of the story. The narrator of GR is a crazed labyrinth tour-guide who’s as likely to whisper a gripping prose monologue as honk a Bronx cheer before screeching hard to the right to show us the nativity of Christ from the viewpoint of cockroaches or take us up on a balloon to fend off a B-17 Flying Fortress with a barrage of custard pies. There is no destination, only the joy of getting there.

Ostensibly, the story takes place in Europe just before the end of the Second World War and in the following nine months. The primary plot involves German rocket attacks on London and Allied intelligence efforts to thwart the effort. One of the novel’s lead protagonists is Tyrone Slothrop, an American intelligence officer who quests for a single rocket, serial number 000000, fired near the end of hostilities; this rocket is mysteriously linked to some dark fact of his infancy. On the other side of the Channel, the German rocket battery commander Weissman (also called Blicero) launches rockets with the ironic intent of somehow escaping from the “cycle of infection and death” (Pynchon, 724).

Pynchon’s rainbow is comprised of many binary forces — art and science, entropy and cybernetics, nature and technology, the rise of the contemporary multinational corporation out of the fallen European order, just to name a few. All of these intersect in one way or another with the Rocket’s assembly under Blicero and Slothrop’s disassembly in the Zone (the area of post-war Germany yet to re-stabilize). As themes proliferate, however, so do stories: Pynchon litters his novel with four hundred other characters and dozens of subplots that randomly surface and sound at the turn of a page. The book ends in the Orpheus Theater in Los Angeles of 1973 where theater manager “Richard M. Zhlubb” — a parody of Richard Nixon — wrings his hands over subversive elements disrupting a movie about death as a nuclear missile screams down onto the roof of the theater.

III. Dominus Blicero, Fire Angel of Europe

The German officer Weissman is a devotee of rocket and Death. They symbolize the only form of love he feels he can can achieve. Weissman (whose name means “White Man”) represents the European yearning for angelic transformation in death. He meditates,

“Want the Change,” Rilke said, “O be inspired by the Flame!” To laurel, to nightingale, to wind ... wanting it, to be taken, to embrace, to fall toward the flame growing to fill all the senses and ... not to love because it was no longer possible to act ... but to be helplessly in a condition of love ...” (Pynchon, 97, author’s ellipses)

Weissman assumes a terrifying stature as rocket battery commander. Questing for godlike control over life and death, he tries to literally personify the Angel of Death. He adopts the name Blicero after Blicker (“White One”), the old German nickname for Death. Taking the German youth Gottfried for a lover, Blicero uses the boy sado-masochistically and then sacrifices him by launching the boy inside the final rocket of his private war.

For Blicero, the Rocket is an extension of his will to break the limits of nature by escaping gravity. In imitation of death’s transformation of life, he commands the Rocket that will take the world into the Other Realm. His homosexuality expresses a defiance of norms and mimics Death’s twisted enthusiasm for life: “Death in its ingenuity has contrived to make father and son beautiful to each other as Life has made male and female” (Pynchon, 723). In sending Gottfried across to the Other Side, Blicero tries to communicate with the Angel the few words he has truly learned in the depths of his solitude. As Rilke sings in his Ninth Elegy,

. . . the wanderer doesn’t bring from the mountain slope

a handful of earth to the valley, untellable, earth, but only

some word he has won, a pure word. . . . (Leishman & Spender, lines 29-31)

Blicero also does this literally by setting up a one-way radio in the rocket’s cabin next to Gottfried. The Rocket is his Angel, vaulting into the catastrophic dark of his love the pure word he has wrested from his despair.

* * *

Freud argued that the self-destructive urges exhibited by Blicero were the result of a long-standing cultural repression of libido: turning negative, Eros transforms into Thanatos, the death-instinct. Thanatos spawns the desire to control and dominate Nature. Technology, the vehicle for this domination, is for Blicero the techne of Transformation.

Rilke, vaguely familiar with scientific discoveries that would spur the developments of the age, sensed in them a vital and even positive metaphor. Douglas Prater notes in his biography of Rilke,

It was perhaps no accident that, reading early in April 1922 of Einstein’s lectures in Paris, and without any real knowledge of his theories, he should feel instinctively that ideas were at work here which could be of capital importance to save our age from condemnation by future generations as only negative and sinister. He regretted his ignorance of these discoveries: “It may be that exclusion from what is happening in mathematics and the natural sciences will bar one for ever from the intrinsic flavor of the fruit that will be ripened in the uncertain climate of this century.” (355)

Pynchon uses a number of scientific metaphors to develop Blicero’s Rilkean vision. Lance Ozier does a wonderful job explicating some of them in “The Calculus of Transformation.” For example, the double-integral symbol SS is recurrent metaphor for the transformative powers of the rocket. Etzel Olsch, architect of the Mittelwerke rocket assembly plant that is carved into a mountain, shapes the plant’s tunnels into a double-integral. Olsch’s “genius” is “fatally receptive to imagery associated with the Rocket:”

... in the dynamic space of the living rocket, the double integral has a different meaning. To integrate here is to operate on a rate of change so that time falls away: change is stilled ... The moving vehicle is frozen, in space, to become architecture, and timeless. It was never launched. It will never fall. (Pynchon, 301; author’s ellipses)

The double integral also identifies the one point in the Rocket’s transit where it finds transformation: Brennschluss, “a point in space where burning must end.”

And what is the specific shape whose center of gravity is the Brennschluss Point? Don’t jump at an infinite number of possible shapes. there is only one. It is most likely an interface between one order of things and another. (Pynchon, 302)

From the double-integral Pynchon extrapolates the metaphor of lightning. Lightning strikes, opening an interface between this and the Other Realm. A double-integral forms the moniker of the SS troops, the lightning-bolts of the Reich, striking blitzkrieg fashion the Fuhrer’s furor. The cataclysm of lightning is holy; ancients believed that those killed by lightning had been touched by God. Pynchon’s narrator informs us,

Most people’s lives have ups and downs that are relatively gradual, a sinuous curve with first derivatives at every point. They’re the ones who never get struck by lightning. No real idea of cataclysm at all. But the ones who do get hit experience a singular point, a discontinuity in the curve of life — do you know what the time rate of change is at a cusp? Infinity, that’s what! A-and right across the point, it’s minus infinity! How’s that for sudden change, eh? Infinite miles per hour changing to the same speed in reverse, all the gnat’s-ass or red cunt hair of the delta-t across the point. That’s getting hit by lightning, folks. (Pynchon, 664; author’s italics)

Just as Blicero strikes lightning into the West, so Death must strike back at Blicero. This is his ultimate invitation. Blicero’s Tarot is read toward the end of the book; the card that covers him is The Tower. “It shows a bolt of lightning striking a tall phallic structure, and two figures, one wearing a crown, falling from it” (Pynchon, 747). What is this cataclysm: orgasm, annihilation, or both? What does the Tower reach for, and what reaches back from the sky? (I can’t help think of Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel painting of the fingers of Adam and God poised like synapses awaiting the spark of life.) Is this Love as only Blicero can imagine? And who is that tumbling with him from the tower? Gottfried? or someone somewhere over the Rainbow? Of course, Pynchon won’t say.

* * *

Does Blicero find transformation? There’s doubt whether he survived the final launch; Enzian conjectures, “If he is alive, he may have changed now past our recognition. We could have driven under him in the sky today and never seen. Whatever happened in the end, he has transcended. Even if he’s only dead” (Pynchon, 660-61).

When Blicero’s Tarot spread was laid out, his Future card was The World. This leads Susan Strehle to conjecture that Blicero’s spirit “transforms” into the nuclear malignancy of the the age. “Blicero stands behind ‘Richard M. Zhlubb’ (Nixon), who manages the theater in which we sit, absorbing images of reality and waiting to be destroyed” (51). Robert Newman agrees: “For Pynchon, Blicero is the face behind the mask of civilization that our culture wears. His unveiling is a warning that, as the descending rocket indicates, comes too late” (132).

Douglas Fowler disagrees. He believes that love was Blicero could only be consummated at Brennschluss, that zenith door into the next realm. The fate of the Rocket in its fall is immaterial to him.

Death is the only way we know to cross the endlessly thinning barrier between the world of our mortal love, inevitably subject to diminishment, and what Rilke imagines as the world on the other side of death, “an altogether surpassing intensity...(where) it is possible to do justice to love.” Weissman’s final speech to Gottfried is an expression of this romantic impulse: “I want to break out — to leave this cycle of infection and death. I want to be taken in love: so that you and I, and death, and life, will be gathered, inseparable, into the radiance of what we would become...” On the other side of death, amidst “the gathered purity of opposites,” they will find a union worthy of them, once and for all. (A Reader’s Guide to Gravity’s Rainbow, 83)

Such twisted love may be the root of the European death-wish, a snake in the grass we cannot see because we look ahead so resolutely. But I don’t think Blicero’s love is merely personal. Blicero wants to transform love through death, but he hearkens to the voice of the Elegies that initiated him in his youth. Rilke’s call is to transform the World. Blicero’s dark union with the Beloved is a mimesis of the Ninth Elegy:

Earth, isn’t this what you want: an invisible

re-arising in us? Is it not your dream

to be one day invisible? Earth! Invisible!

What is your urgent command, if not transformation?

Earth, you darling, I will! Oh believe me, you need

your Springs no longer to win me: a single one,

just one, is already more than my blood can endure.

I’ve now been unspeakably yours for ages and ages.

You were always right, and your holiest inspiration’s

Death, that friendly Death. (transl. Leishman & Spender, 68-76)

That is why Blicero’s future Tarot card is The World. It his destiny to bring Death out of hiding and hang its black canker like a garland in the sky.

* * *

Blicero is the death impulse that brings the Rocket to a summit, and notches the nuclear clock a “gnat’s ass” from White Noon. Pynchon has taken Rilke’s Elegies to their zenith. Now what happens? The final lines of the Elegies suggest a turn:

And we, who have always thought

of happiness climbing, would feel

the emotion that almost startles

when happiness falls.

(Tenth Elegy, transl. Leishman & Spender, 110-13)

IV: Slothrop, Harp-Minstrel of the Zone

These early Americans, in their way, were a fascinating combination of crude poet and psychic cripple. (Pynchon, 738)

* * *

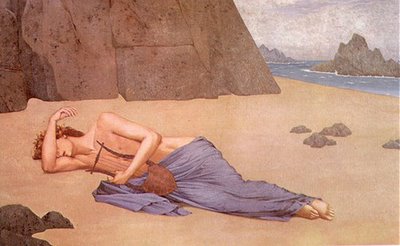

Tyrone Slothrop, innocent American, lower-echelon intelligence officer, presents Blicero’s opposite on the other side of the Rainbow. If Blicero consciously seeks to find love in death, Slothrop is an unconscious Orpheus who transforms death back into life through his fragmentation and scattering throughout the world.

Slothrop begins as an inanimate character; he is what Rilke lamented in 1925 that “Now there come crowding over from America empty, indifferent things, pseudo-things, Dummy Life” (Leishman & Spender, 129). Slothrop is fated to sterility by a long line of Puritans who earned their lucre by cutting down trees. His ancestors “… carried on their enterprise in silence, assimilated in life to the dynamic that surrounded them thoroughly as in death they would be to churchyard earth. Shit, money, and the Word, the three American truths, powering the American mobility, claimed the Slothrops, clasped them for good to the country’s fate. But they did not prosper ... (Pynchon, 28, author’s ellipses)

As an infant Slothrop is subjected to psychological experiments involving sex and a new plastic; as payment, his parents receive in enough money to finance his later Harvard education. His sexuality, damaged by this intrusion, will later animate him in demonic ways; but his family saw it as a profitable exchange. Slothrop is also manipulated by all the jive of American culture. His brain babbles with the drama of comic books and Hollywood movies. Inflamed by patriotic rhetoric, Slothrop joins the boys across the sea late in the war effort. In London he divides his time between intelligence efforts, avoiding the hail of A-4 rockets, and chasing skirts. If Slothrop has any depth, he’s entirely unaware of it.

Slothrop may be an all-American boy, but something about him really disturbs his superiors. It seems that Slothrop fastidiously maintains a map of real (or imagined) sexual conquests; unbeknownst to him, each new flag he plants on the grid prophesies by several days the exact location of the next rocket’s fall. Slothrop infant conditioning and the rockets attune to each other through Impolex G, the mysterious plastic. His sexual arousal and conquests are either an invocation or prophesy of England’s destruction. Slothrop is vitally, perhaps virally linked to Blicero.

Pointsman, his intelligence superior, cannot abide such a mystery. He’s a Pavlovian who believes, like his mentor, that “the ideal, the end we all struggle toward in science, is the true mechanical explanation” (Pynchon, 89). Pointsman launches a covert campaign to destroy whatever dark shadow lures women to Slothrop and rockets to London:

Does news from the front affect the itch between their pretty thighs, does desire grow directly or inversely as the real chance of sudden death - damn it, what cure, right in front of our eyes, that we haven’t the subtlety of heart to see? . . . But if it’s in the air, right here, right now, then the rockets follow from it, 100% of the time. No exceptions. When we find it, we’ll have show again the stone determinancy of everything, of every soul. There will be precious little room for any hope at all. You can see how important a discovery like that would be. (86)

Little matter that Slothrop may be annihilated in the effort to twist his conditioning around. Pointsman imagines a Nobel prize for himself if he’s successful.

Suspicious of the plots that begin to unfold around him, Slothrop grows increasingly paranoiac. He tries to escape the clutches of the System by fleeing to the Zone of postwar Germany where boundaries and authority have yet to re-establish. Tony Tanner describes Slothrop’s paranoia:

Paranoia is, in terms of the book, “nothing less than the onset, the leading edge, of the discover that everything is connected, everything in the Creation, a secondary illumination - not yet blindingly One, but at least connected” (703). . . . The opposite state of mind is anti-paranoia, “where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long” (434). . . . as figures move between System and Zone, so they oscillate between paranoia and anti-paranoia, shifting from a seething blank of unmeaning to the sinister apparent legibility of an unconsoling labyrinthine pattern or plot. (81, author’s ellipses)

Slothrop’s Paranoid Phase involves him in a strangely-connected web of bureaucracies small and big: government agencies of a dozen nations, cartels and corporations, cabals and black markets, all staffed by zealots, enthusiasts and operatives of every sexual and narcotic persuasion, each chasing one grail or another that inexplicably weave through each other like fine lace.

Descent is the dominant motion for Slothrop, for he represents that half of Rilkean experience that locates divinity by reaching into the earth and the lower regions of consciousness. Orpheus must enter the dark realm because

Only one who has lifted the lyre

among shadows, too,

may divining render

infinite praise.

(Sonnets to Orpheus 1.9, transl. Norton)

This way of knowing is dark, sinister, outside all systems; for all those like Slothrop in the Zone, “with the greatest interest in discovering the truth, were thrown back on dreams, psychic flashes, omens, cryptographies, drug-epistemologies, all dancing on a ground of terror, contradiction, absurdity” (Pynchon, 582). All these participate in the rhetoric of descent; they flow into the inferior, gnostic stream of the Western unconscious.

Slothrop searches the Zone for the Schwarzgerat or “Blackrocket,” the mystical rocket with the serial number 00000 (the holy Zero). For Slothrop, the quest is consistent with his tampered libido, for it is watered by a ceaseless serial of affairs. Women take him in, embrace, let him go. Some are young, tender, giving; others older, hardened, cruel. Like Orpheus, Slothrop resonates with the beauty and terror of feminine nature. Marjorie Kaufman notes that the appearance of young women in the novel “seem to cluster particularly at moments of change: recovery, location, season,” (202) while “The Mothers of GR . . . are a perversion of the ‘girls.’ Their wombs nourish life, but their children once born take from their breasts not only physical strength but a taste for death, an aptitude for dying” (210).

Boarding the ship Anubis (named after the Egyptian jackal-god of the dead) Slothrop meets and falls in lust with Bianca, the daughter of his current lover. The ship is filled with displaced nobility of all nations and is engaged in a free-floating, whimsical orgy. Slothrop and the girl have sex; afterwards she offers love and protection. Slothrop is aware of the possibility of the moment: “Right here, right now, under the make-up and fancy underwear, she exists, love, invisibility ... For Slothrop this is some discovery” (Pynchon, 470, author’s ellipses and italics).

But Slothrop’s power does not extend to love. “Sure he’ll stay for a while, but eventually he’ll go, and for this his is to be counted, after all, among the Zone’s lost. The Pope’s staff is always going to remain barren, like Slothrop’s own unflowering cock” (Pynchon, 470). Thrown overboard, Slothrop eventually returns to ship, not to rescue Bianca, but to retrieve a packet of dope for some drug dealer. It’s stashed in the engine-room where he and Bianca once had sex. Someone cuts the lights as he tumbles down the ladder, and fumbling around in the dark he feels a body swinging on a noose, reeking of “perfume and shit and the smell of brine” (Pynchon, 531). Slothrop now faces the Eurydice whom he had left behind on the jackal-ship of the dead: a vision strikes him like lightning.

When the lights come back on, Slothrop is on his knees, breathing carefully. He knows he will have to open his eyes. The compartment reeks now with suppressed light, with mortal possibilities for light — as the body, in times of great sadness, will feel its real chances for pain: real and terrible and only just under the threshold ... The brown paper bundle is two inches from his knee, wedged behind the generator. But it’s what’s dancing dead-white and scarlet at the edges of his sight ... and are the ladders back up and out really as empty as they look? (532, author’s ellipses)

The boy who has never looked back is forced to see the truth of his departures. He looks upon his Eurydice, and it is he who begins to vanish.

* * *

After the Anubis episode, Slothrop’s paranoia suffers entropy. He begins to “thin, to scatter” (Pynchon, 509). Where Blicero intensifies into the double-integral of timelessness, Slothrop disappears into the Zero of the present. Scattering is consistent with Orpheus, who was torn apart by the maenads of Dionysos:

In the end they battered and broke you, harried by vengeance,

the while your resonance lingered in lions and rocks

and in the trees and birds. There you are singing still.

O you lost god! You unending trace!

Only because at last enmity rent and scattered you

are we now the hearers and a mouth of Nature.

(Sonnets to Orpheus 1.26, transl. Norton)

Fate cuts Slothrop loose from the paranoiac net of The System — Pointsman’s final solution of having Slothrop castrated backfires when the wrong man goes to the knife. Embarrassment over the incident places official sanction on Slothrop’s freedom. Slothrop disappears into Pynchon’s Preterite — those passed over by God, no longer a part of history. Slothrop heads for the Harz mountains, “letting hair and beard grow. . . . He likes to spend whole days naked, ants crawling up his legs, butterflies lighting on his shoulders, watching the life on the mountain. . . . He’s been changing, sure, changing, plucking the albatross of self now and then, idly, half-conscious as picking his nose” (Pynchon, 623).

One day Slothrop finds the harmonica he lost down a toilet in the Roseland Ballroom before the war. It is a gift from unseen powers in recognition of Slothrop’s Orphic election and scattering. He has disappeared into the waters:

“. . . there are harpmen and dulcimer players in all the rivers, wherever water moves. Like that Rilke prophesied,

And though Earthliness forget you,

To the stilled Earth say: I flow.

To the rushing water speak: I am. (Pynchon, 622)

Here Slothrop quotes Rilke’s final Sonnet to Orpheus, which tells us he as completed his transformation. He lays down one day and forms a “crossroads” with his outstretched limbs. It is a place

. . . where you can sit and listen to traffic from the Other Side, hearing about the future (no serial time over there: events are all there in the same eternal moment and so certain messages don’t always “make sense” back here: they lack historical structure, they sound fanciful, or insane). . . . After a heavy rain he doesn’t recall, Slothrop sees a very thick rainbow here, a stout rainbow cock driven down out of pubic clouds into Earth, green wet valleyed Earth, and his chest fills and he stands crying, not a thing in his head, just feeling natural. (Pynchon, 626)

* * *

What’s happening here? Although it’s clear that Slothrop imitates the Orpheus of Rilke’s poem, critics disagree on Pynchon’s treatment of the myth and of Rilke. Thomas Schaub thinks Slothrop’s experience falls short of the Rilkean:

The difficulty in trying to use these lines as an interpretive key to Slothrop’s experience is that Tyrone’s character cannot bear the weight of Rilke’s poetry. This apparent contradiction between ideas and drama is characteristic of Pynchon’s writing; that is, the dissonance between the idea-nexus Pynchon brings into play, and the dramatization of character within that nexus, means neither that Rilke is a red herring nor that Tyrone achieves Rilkean transcendence.

Tyrone does become a “living intersection,” but if this is a Rilkean event, it is necessarily without the joy attendant upon salvation; this salvation is “impersonal” and involves forsaking the very ego which wanted saving in the first place. (72)

According to Edward Mendelson, Slothrop’s refusal of responsibility slips him below the human into animal unconsciousness — hardly a noble attribute:

Slothrop progressively forgets the particularity of his past, and replaces his memory of past events with garish and crude comic-book versions of them. His disintegration of memory is not the work of those who oppose or betray him, but is the consequence of his own betrayals, his own loss of interest in the world, his own failures to relate and connect. . . . What Slothrop no longer remembers is that his actions occur not for their own sake, or for his, but in a complex of meaning, a Sinnzusammenhang of ethical responsibility. . . . Separated by his own escape and his own empty freedom from an originating past or a future to which he could be responsible, Slothrop can only diminish and disintegrate. (183)

Susan Strehle argues that Slothrop is a realist who is unable to “read” or adjust to the randomness of the Zone, and so reverses into a more frightening persona:

He brings Newtonian assumptions to his reading of reality until his experience forces him to abandon them; then, unable to imagine other alternatives, he simply turns Newton’s cosmos on its head and envisions its binary opposite. . . . Slothrop abandons realism for surrealism. He “flips” from causality and “flops” for chaos. . . . Slothrop unreflectively ignores a range of middle possibilities, that some things might be connected, loosely and mysteriously. (389)

Accordingly, Strehle thinks Pynchon uses Rilke with dark irony. Blicero and Slothrop, the two characters who quote Rilke, are monstrous “antithetical doubles:”

. . . they can be imagined as zero and one, where both points represent different forms of death, and life occupies the excluded middle ground. While Slothrop abandons connections, including those linking his various selves, and thus loses human identity, Blicero pursues linear connections to their inevitable end in death and thus loses human identity. Slothrop ceases to make fictions about his own role, and Blicero constructs a perfect, closed fiction; both thereby deny themselves living roles. Slothrop, the realist-turned-surrealist, abandons the quest for coherence at the cost of life; Blicero, the romantic, pursues an exclusive, even monomaniacal coherence at the cost of life. Blicero, the anti-Slothrop, achieves prominence in GR’s last movement partly because his yearning for a climactic, ego-affirming end at once parallels and opposes — and both ways illuminates — Slothrop’s own anti-climactic and ego-dissolving end. (50-1)

In my opinion, Slothrop’s ego is annihilated, but Pynchon doesn’t think that’s all that bad. Why? Because the disease is in the ego: “The Man has a branch office in each of our brains, his corporate emblem is a white albatross, each local rep has a cover known as the Ego, and their mission in this world is Bad Shit” (Pynchon, 712-13). If freedom and truth exists, it must have a different center than the ego — a wider base.

Rilke believed that descent from the ego was necessary to truly enter the world:

It seems to me more and more as though our ordinary consciousness inhabited the apex of a pyramid whose base in us (and, as it were, beneath us) broadens out to such an extent that the farther we are able to let ourselves down into it, the more completely do we appear to be included in the realities of earthly and, in the widest sense, worldly, existence, which are not dependent on time and space. From my earliest youth I have felt the intuition (and have also, as far as I could, lived by it) that at some deeper cross-section of this pyramid of consciousness, mere being could become an event, the inviolable presence and simultaneity of everything that we are, on the upper, “normal,” apex of self-consciousness, are permitted to experience only as entropy. (Mitchell, Selected Poetry of Rilke, 324, author’s italics)

Where Slothrop’s scattering and dissolution reads like a classic schizophrenia — that is to say, extreme ego-entropy — we can’t help but feel that Slothrop has somehow entered a state of grace. There never was much hope for poor Slothrop, but now at least he’s safe, “among the Humility, among the gray and preterite souls ... adrift in the hostile light of the sky, the darkness of the sea ...” (Pynchon, 742, author’s ellipses)

V: Conclusion

One of the final sections of the book is titled “Orpheus Puts Down Harp” and takes place in Los Angeles of 1973 (the year GR published). It’s an unhappy scene: Orpheus Theater manager Richard M. Zhlubb is upset because some anarchist harmonica-players are disrupting the “Bengt Ekerot/Marie Casares Film Festival” (these were actresses who portrayed Death in movies like Bergman’s Seventh Seal and Orphee, Jean Cocteau’s recasting of the Orpheus myth). Is Slothrop among them? Suddenly air raid sirens peal the air: what approaches? Is Blicero’s nuclear winter about to descend? The narrative breaks up here, jumping abruptly back to the firing of the Rocket 00000; then returns to the present as a rocket screams down toward the roof of the theater.

The question looms: is this the great white Silence? The answer appears to be no, for on the last page of the book the author invites us all to sing along with the hymn penned by Slothrop’s ancestor William:

There is a Hand to turn the time,

Though thy Glass today be run,

Till the Light that hath brought the Towers low

Find the last poor Pret’rite one ...

Till the Riders sleep by ev’ry road,

All through our crippl’d Zone,

With a face on ev’ry mountainside,

And a Soul in ev’ry stone ...

(Pynchon, 760, author’s ellipses)

I read the song as the heart of Pynchon’s affirmation of Rilke. Lightning strikes Tower and Preterite, scattering Blicero and Slothrop. But the rainbow that follows is a celebration of that fact. Although the Zone of possibility is crippled by ever-more-efficient Systems of deathlike control, there still thrives a possibility for grace in each moment. Like the island of Avalon in the Arthurian cycle that each year becomes harder to find, occasionally Pynchon lifts the mist over his vast and dark landscape, and we see the deity Blicero etched on the face of the mountain heights of our impossible longing, hear Slothrop singing in every stone.

Pynchon’s music comes from Rilke: it is an undaunted music of transformation that rises and falls, terrifying to embrace, and yet it is the small margin of our hope. It is an admonition straight from the greatest of Rilke’s Sonnets:

Be ahead of all parting, as though it already were

behind you, like the winter that has just gone by.

For among these winters there is one so endlessly winter

that only by wintering through it will your heart survive.

Be forever dead in Eurydice — more gladly arise

into the seamless life proclaimed in your song.

Here, in the realm of decline, among momentary days,

be the crystal cup that shattered even as it rang.

Be — and yet know the great void where all things begin,

the infinite source of your own most intense vibration,

so that, this once, you may give it your perfect assent.

To all that is used-up, and to all the muffled and dumb

creatures of the world’s full reserve, the unsayable sums,

joyfully add yourself, and cancel the count.

(2.13, transl. Mitchell)

***

(email me if you want to see the works cited)

<< Home